The Eagle is a vivid and at times lucid action adventure, a step above Ridley Scott‘s Robin Hood, owing more to Terrence Malick with a nod to Italian neorealism than anything else. The true star of the production is Anthony Dod Mantle’s cinematography, capturing with a sense of spontaneity light and dark, interior and exterior and especially moonlight, beautifully.

The Eagle is a vivid and at times lucid action adventure, a step above Ridley Scott‘s Robin Hood, owing more to Terrence Malick with a nod to Italian neorealism than anything else. The true star of the production is Anthony Dod Mantle’s cinematography, capturing with a sense of spontaneity light and dark, interior and exterior and especially moonlight, beautifully.

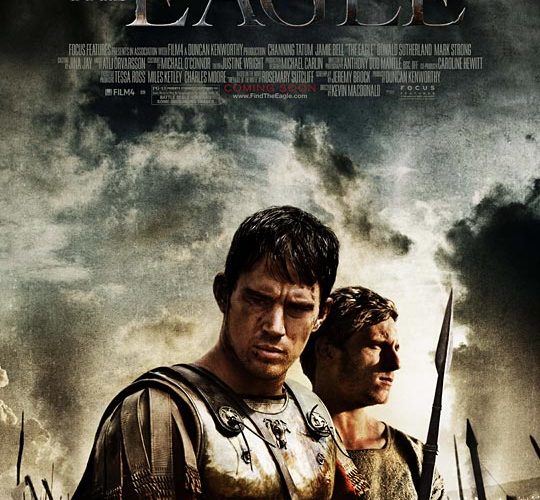

Channing Tatum is Marcus Aquila, a Roman soldier who seeks out a lost golden emblem of his father’s legion in Roman-occupied Britain. He is a heroic pro-life warrior, given an honorable discharge after his battle wounds and service in a standard large, and somewhat confusing battle, that are standard in these pictures (although this has a great and slow build, including an excellent if not unoriginal tracking shot through a field in moonlight and other natural light sources) ends. Being pro-life, he saves a young slave named Esca (Jamie Bell). The film’s director, Kevin Macdonald, holds the line and never permits the film to become a “buddy road movie.” Indeed this is a rarity in a system of manufacturing film product. That said, the film edges towards poetics while holding that line between hybrid spiritual and action-adventure journey.

Macdonald’s career is stock-piled with thrillers, including a few that are in the form of documentaries, like his Oscar-winning One Day in September, Touching the Void and My Enemy’s Enemy. There’s also the compelling narrative features The Last King of Scotland and State of Play. Politics play a part in both of those past features, Macdonald turning his lens on war criminals and the Washington power structures and the relevancy of journalism.

As a political thriller The Eagle is not a misfit – the film is an exploration of the notion of “national state.” It’s an idea that exists within the hearts and minds of those that believe to belong to such a unit, artificial or officially bordered. Donald Sutherland‘s portrait of Marcus’ wise old uncle provides a link to the past and the moral grounding for Marcus to save Esca at a mini-scale gladiator event that looks like something at a state fair, just one of the many details the film’s sets and restraint from CGI provide. CGI has the ability to show us things that perhaps could have never existed. Macdonald restrains the “eye of god” point of view, keeping the drama and the action where it belongs, at human scale.

A great debt in keeping scale is owed by Mantle’s cinematography. The editing, by Justine Wright, in the battles is standard. If you’ve seen Ridley Scott‘s Robin Hood and the Lord of the Rings series you know what I mean, but the moments edging towards the epic battles contain an atmosphere all their own, a refreshing humanistic approach to the genre. Perhaps informed by Macdonald’s last project, Life in a Day, where he has stated in interviews he found there are common bonds amongst humans, their dreams, aspirations, goals and outlook as he “collaborated” with thousands of “co-directors” world-wide. The Eagle is just smart enough to operate without the auto-pilot function of many action adventures where you simply don’t care what happens next.