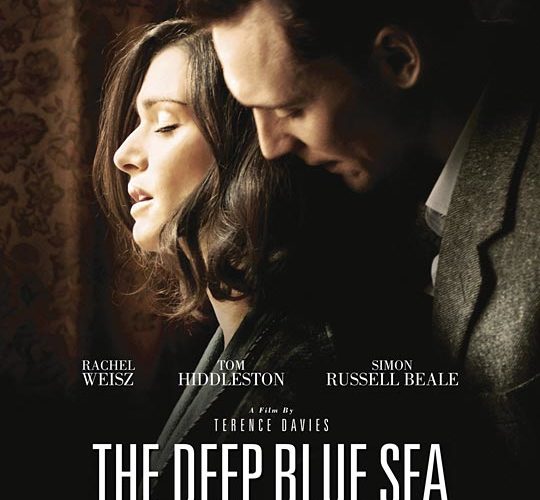

It takes only a moment to drop a bomb, but it can take years to clean up the devastation it leaves in its wake. Such is the case for post-Blitz London, with its damaged flats and crumbled cathedrals, which makes a fitting backdrop for The Deep Blue Sea, Terence Davies‘ newest film as writer/director since 2000’s The House of Mirth.

Hester Collyer (a brilliant Rachel Weisz) is not long for this world. Or at least that’s the hope. Through a kaleidoscopic opening nine minutes, we get the speed-through of the steps she’s taken to end up in this dingy apartment, the kind where you have to pay for the gas in the heater, coin by coin. It makes for a very tedious and costly suicide attempt. Collyer sits on the love seat, taking languid drags of her cigarette, watching as it slowly burns to ash. She probably takes it as a mirror.

Hester Collyer is married to Sir William Collyer (Simon Russell Beale), a distinguished judge who has all the trappings of success in the class divided strata of British society: namely power and money, though not necessarily in that order. He is a kind man, a caring man, who dotes over Hester as if she was a princess and he an errand boy. But Hester doesn’t want a helper, she wants a husband. And a passionate one at that.

This proves impossible, as a trip to his childhood home reveals an alarming devotion to mommy (Barbara Jefford), refusing to make a fuss when the married couple has to sleep in separate beds. Sure, the film is set during the Hays Code, but life needn’t imitate art. This hands-off devotion has been suitably passed down; the mother speaks highly of her garden, and the “guarded enthusiasm” that it brings her. No wonder William’s as stiff as his starched collar.

No wonder then that Hester is charmed into the arms of Freddie (Tom Hiddleston), a handsome, debonair man she meets at the local country club. In classic theatrical form, he is William’s foil: young, energetic, and quick with his tongue, engaging in playful banter with Hester who’s too moonstruck by the sight of him to even help to respond.

Hester falls head over heels in love not just for his looks or demeanor, but for his care, a care that is separate from William’s. The only glimpse we get of a sex scene between the two comes early in the movie and after the act itself. She doesn’t want the action but rather the embrace. Her memory focuses on their bodies entwined…something not exactly possible with your husband when a night stand stands between.

This film hinges on choices, ones that are forced upon you and ones that are made with finality. Hester chooses to dive deeper into her relationship with Freddie, driving herself further from her marriage with William. When Sir Collyer finds out about this infidelity, this horrible slight, he chooses to banish her. He grants no divorce, no settlement, no contact; just the ability to go off with her lover, whomever it may be.

Freddie did not choose to be a fighter pilot. He did not choose to watch as his mates died in pieces spread over France, nor did he want to feel the horrible adrenaline of a kill-or-be-killed scenario fought perilously up above a war-torn Europe. It’s the experience that forever defines him, for good and for ill. When Hester moves in with him, a move that he did not necessarily see coming, it brings to light just how much stress still sits on his shoulders.

That’s the thing about choices. No matter if you choose the right or wrong, you still have to live with the consequences. And in a world where your choices are so limited–her suicide attempt is technically against the law, making Hester not even empowered enough to take her own life–is it more important to make the right choice, or to be able to make one at all?

By the looks of it, you’d think that Davies spent all of the last ten years crafting The Deep Blue Sea. It is a lovingly made film with a laser focus. The pace is deliberate, and purposefully so. These are smart, measured people making calculated risks while weighing out long term consequences. It’s an adult film, with adult issues, that are solved in adult ways.

But that’s not to say that it is slow, dreary, or that it isn’t clever. It’s marvelously so. This is the kind of movie where you feel the wit of the filmmaker as the mise en scene breezes by. Of course she tries to die through the gas through the heater: her flame has burnt out. Of course one of Freddie’s screaming matches is punctuated by an arrow with “GENTS” stuck into the middle of it, and of course that’s the way he exits the scene.

It’s a trick of James Merifield‘s production design (highlighted by a flashback where all walks of life are trapped in The Underground as the bombs drop and the sign saying “Keep It Under Your Hat” comes into focus on a wall) but also the sure hand of a studied director. Davies throws himself on the screen, aided no doubt by his experience growing up in this era, himself born in Liverpool, 1945. While getting the tone and tenor right (this from someone born in New Jersey, 1986) is admirable, the real trick is taking a simple question (“what does one value in a relationship?”) and keep that plate spinning for the entire run time. While everything else seems to crumble, Davies builds something solid, pristine, and lasting.

The Deep Blue Sea is in limited release beginning March 23rd. Click here for a list of venues.