Yours truly has struggled to understand how much Lee Daniels, the eponymous director of / possessor in Lee Daniels’ The Butler, is playing his new film as a wink and nod. The true story of the White House’s black butler gaining a head-on view of the changing social landscape sounds, if only on paper, somewhat familiar — akin to the likes of The Help or Driving Miss Daisy, perhaps; what your older relatives especially enjoy — and notwithstanding the fact that action glides in this register for roughly half a total runtime, something altogether stranger seems to be happening at the margins. Even if Daniels and scribe Danny Strong (a fit, considering his credits on the HBO political movies Game Change and Recount) fall short of a historical picture with more to say about the genre and our conceptions of passing ages, the path which we follow comes tantalizingly close — a picture that emerges unexpectedly worthwhile, in equal part because of its palpable strengths and more peculiar flaws.

Yes, this story of American civil rights contains the requisite moments of diner sit-ins and hosed-down protestors — with an appearance by Martin Luther King Jr., for good measure — but these are side strands to the more stripped-down central narrative of Cecil Gaines, a middle-aged black man hired, during the Eisenhower administration, to serve as butler in the White House. His is an affable personality: aside from a cumbersome “old-man” voiceover and somewhere around two or three character introductions, Gaines is scripted and, by Forest Whitaker, played with a level of humanity that never falls into the maudlin or emotionally grabby. It’s a character whose navigation through several decades yields genuine complexity, and it’s a performance that works mainly on account of Whitaker digging deep, finding the necessary physical poise and worn-down, gentlemanly manner to illustrate a one-man history without ever needing to speak a word.

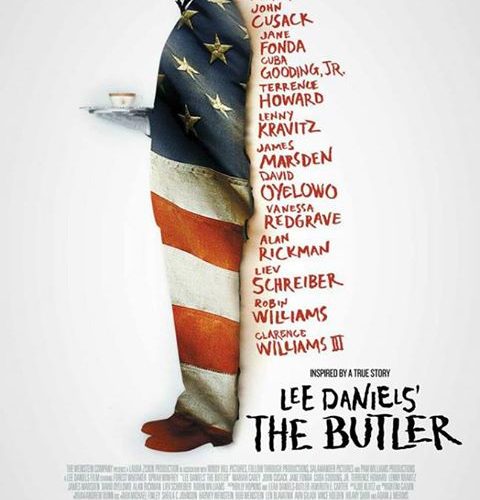

But Daniels, himself, is clearly most comfortable when getting people to talk, letting his ensemble play off one another and watching their chemistry take a scene wherever proves necessary. A number of The Butler’s performers prove strong in ways they haven’t for some time; it’s enough of a wonder that Whitaker, Cuba Gooding Jr., Lenny Kravitz, and Terrence Howard — four actors yours truly has always been mixed on, rarely appreciating as much as a whole performance — would all prove welcome screen presences, even more so when a number of these men are grouped together at a single point in time.

Little surprise, then, that progression in narrative more and more clearly illustrated how preferable a White House-centered drama would have proven: while these scenes have a loose, charming demeanor — to say nothing of a behind-the-scenes glimpse at dealings in the White House kitchen, which reveals without steeping in historical record — the momentum for which they’re responsible is thrown off balance as soon as The Butler cuts back to Cecil’s home life, a series of familiar incidents that neither illuminate the man at its center or, worse yet, give his narrative some significant length of conflict to eventually surmount. There’s the wife, Gloria (Oprah Winfrey) — whose alcoholism is a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it debilitation that’s casually introduced when more dramatic weight is needed — and an older son, Louis (David Oyelowo), is more concerned with the African American ascension of social ladders than his kind, amiable father can fully tolerate. It’s in this latter section where the picture’s scope both expands and, in some sense, contracts, providing a series of sequences that, properly documented and harrowing though they are, rarely feel to have a proper coalescence with the central action.

Successful or not, witnessing this narrative volley brings enough entertainment and basic critical consideration to provide the occasional distraction from Daniels being an uncontrolled filmmaker. Where he gets the period details right, he can’t be bothered to nail the crucial sense of texture — at its worst, The Butler’s digital cinematography, from Andrew Dunn, often has a muddy quality — and though a number of nice, stern compositions can be found, he often feels impatient, moving the camera and cutting around a scene when no need existed. It was a manic time, yes, but his occasionally manic formal portrait is cumbersome no matter the context.

For all the social pretenses his film adopts, Daniels is clearly most-relaxed when filming in the White House — the scenes are brisk, funny (a surprisingly appropriate looniness even creeps in), and bring with them the level of atmosphere those sequences set apart from 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue could’ve benefited from. The Butler has little in the way of overall consistency, but it’s at these points where, not for nothing, proceedings are at their most entertainingly inconsistent. The gallery of leaders is mostly akin to a Hall of Presidents recreation, no more than when those who require makeup so rarely looking “correct”; the main exception is Alan Rickman as Ronald Reagan, his set of sequences — both in the actor’s presence and (too-)short scripted arc — nailing the ambivalent, strangely uncomfortable kindness his public demeanor was best-known for.

Yet, for these issues, it’s difficult to deny that some implicit entertainment stems from the turn of things. Why Robin Williams as Dwight D. Eisenhower? Why Liev Schreiber as Lyndon B. Johnson? Daniels would appear disinterested in any reason that goes past “because,” but an acceptance nevertheless opens his film to the humorous value much of these moments coast on. In one other case, the commander-in-chief’s presence is outright surreal: John Cusack’s turn as Richard Nixon is among the more baffling I’ve seen in years, this presence little more than the actor in a suit, putting on a voice and well-known affectations while still being, completely and totally, John Cusack. (The audience didn’t appear to realize who he was playing until a voice came out.)

But this lens on the nation’s larger historical matters — Vietnam, one key example; the perspective on events down South connecting one side of the narrative with another — is too simple to be entirely justifiable, Daniels’ frequent handling by way of montage giving the unfortunate impression of a history highlight reel more than any kind of ample document. What’s more, the general ambition that this kind of project brings — not merely to tell an inspirational story about change, but the man who witnessed it all — brings into question the veracity of its historical explorations. Did he so often walk into the White House as matters of race relations were being discussed? Did Nixon and Reagan share those revealing, heart-to-heart moments? It befits the movie’s uncommon historical register, still, for Strong’s screenplay to be at its most curious when focus shifts toward the West Wing; in that, a shady crossing of fact and myth can not only be forgiven, but relatively encouraged. If for nothing else, it creates more tenable a cinematic environment than some brisk looks inside the Black Panther party — one of many refreshingly non-reactionary, albeit stock points in the narrative scope.

This mix and match leaves us wondering if Daniels and Strong were aiming for a historical picture with more subversive underpinnings — one of the few lines given to Martin Luther King Jr. (played by Nelsan Ellis) would serve as indexical evidence of this intent — and, while the film gets at that to certain degrees (these aforementioned Reagan moments stick out), The Butler’s final notes have too strongly followed through on traditional, slightly staid dramatics to have it both ways. But it was an effort worth parsing.

Lee Daniels’ The Butler opens on Friday, August 16.