Ahead of the Academy Awards, we’re reviewing each short category. See the Live Action section below and the other shorts sections here.

Detainment – Ireland – 30 minutes

Two ten-year-old boys were placed into police custody in 1993 on suspicion of kidnapping and murdering the not-yet three-year-old James Bulger in Merseyside, England. They were interrogated separately with parents present about their whereabouts on that fateful day and whether or not they were guilty of the crime. It’s unfathomable to believe children so young could have done what they did, but it’s even harder to comprehend them lying about it when the truth starts to spill out. These interviews were recorded and eventually released as a matter of public record with certain tapes remaining sealed due to the graphic nature of what was described. The pair served eight years with appeals of fair trial violations reducing their sentences before receiving new identities in the aftermath.

There’s no question they did what they did regardless of whether trying them as adults was handled the correct way. It’s a tragedy with far-reaching consequences when you think about the psychological ramifications and subsequent crimes upon release, but these perpetrators could never earn more sympathy than their victim. So don’t think Vincent Lambe’s short reenactment of those transcripts might somehow be looking to give them a voice, assume remorse, or pick sides as far as who put whom up to homicide. Detainment is merely a fictionalized document of what happened inspired by the defendants’ own words. It’s a look at young minds and their ability to compartmentalize, skew facts, and elicit a reaction. We see defense mechanisms, stubborn plays at one-upmanship, and the resignation of coming clean.

It’s an impossibly arduous series of events to experience — especially as someone unaware of the case’s details. I’ve heard the name James Bulger (Caleb Mason) and had a dim recollection of his death if only because Jon Venables (Ely Solan) and Robert Thompson (Leon Hughes) became the youngest convicted-as-adults murderers in British history. Seeing their childish antics robbing stores and running around before spying young James alone outside the butcher shop doesn’t, however, prepare you for what happens next. You assume they left the toddler, accidentally watched him fall into a canal, or lost him before deciding to just go home. You assume Jon’s tears portray the truth as being simple just as Robert’s stoicism presumes possible premeditation. Just know there’s a reason that last interview remains sealed.

Lambe coaxes fantastic performances from these two youngsters going above and beyond to embody monsters that may not have a full grasp on what it is they did. Hughes’ ambivalence opposite stone-cold police officers is scary while Solan’s deluge of emotions would border on histrionics if not for the sheer terror in his eyes. You have parents slowly realizing what their boys have done while the detectives drop their poker faces to get to the heart of the unspeakable punishment little James endured. One boy defaults to using “we did ___” while the other keenly distances himself with a “he did ___” instead. Eventually the mask of innocence is torn off to reveal the most terrifying truth of all: evil has no prerequisites and knows no bounds.

A-

Fauve – Canada – 17 minutes

Youthful thoughts of immortality have a way of getting children into trouble as well as teaching them lessons able to scar them for life. For Tyler (Félix Grenier) and Benjamin (Alexandre Perreault) it’s a seemingly innocent game of one-upmanship wherein an indefinable state of superiority earns each a point on their way to a winning total of six. So if one feigns an injury and the other is gullible (read compassionate) enough to help, the trickster adds to his total. If one is in the process of causing injury and the other begs for it to stop — that’s another tally in the column for the perpetrator. The game is pretty much a construct that allows them to test the other’s boundaries and prove their mettle by sowing mistrust.

Writer/director Jeremy Comte isn’t trying to create a sense of animosity in this depiction, though. The two boys in Fauve genuinely hold a kinship for one another within their ill-advised route towards fun. Just because they find their empathy numbed in the context of this voluntary struggle for dominance doesn’t mean there aren’t also moments when helping each other becomes a second-nature act. These are “boys being boys” as they run around an environment blocked off from the public for good reason. The beauty of this man-made surface mine attracts them with its mountains of sand and expanse for adventure, the danger it holds unfathomable for two adolescents unworried about consequences far-removed from supervision. So there’s zero safety net once they inevitably take their fateful misstep.

You have to wonder where Comte is going with this drama after tragedy arrives because it would be easy to go one of two obvious directions: have it all be another “joke” or make us witness the devastating fallout upon returning home. Because his story is short, however, he doesn’t have to copout or expand further than the microcosm of youth he’s supplied. In this way Comte chooses to stay in the isolation of the boys’ world, amplifying its futility instead of introducing external forces for punishment and/or consoling. He started with Tyler and Benjamin running wild with no one but each other to prop up or tear themselves down and remains with them to the end because the most powerful form of sorrow always rises from within.

B+

Marguerite – Canada – 19 minutes

Stereotyping is proven real when an elderly Marguerite (Béatrice Picard) asks her nurse Rachel (Sandrine Bisson) if the person she was talking to on the phone was her boyfriend only to hear, “My girlfriend” instead. The woman’s face drops in surprise with an, “Oh” before finding a smile and the kindness to ask her name. We wonder if things will now change between them, assuming a senior citizen wearing a crucifix might not “approve” of such behavior. How will Marguerite react the next time Rachel rubs lotions into her legs? Will she even get the chance to return? I won’t lie and say my mind didn’t automatically think the worst, cringing to discover where it all might go with a generational gap today’s world knows only too well.

What Marianne Farley’s short Marguerite delivers, however, is very much the opposite. Where I feared animosity and bigotry, she drew compassion and love. Where the close-quarters of preconceptions threatened to box characters in, Farley built a depiction of the complex understanding that moves us beyond empathy into something more akin to admiration and perhaps a positive dose of jealousy. We’re so quick to dismiss older people as being unable to wrap their heads around contemporary truths that we forget to consider the vastly different and archaic circumstances under which they were nurtured and ultimately conditioned. Maybe instead of revulsion, this revelation on behalf of Rachel could conjure nostalgia. Perhaps hindsight will remind Marguerite of similar feelings she repressed for survival rather than nourished for happiness.

The result is a sweetly touching tale of kinship wherein our own conditioning to refuse giving past generations the current benefit of the doubt makes looks appear deceiving. Farley isn’t intentionally manipulating us into thinking ill of Marguerite, though, because she knows some of us will by default. And whether or not we’re within that category of viewers, the endgame of humanistic warmth is still achieved. Some will interpret Marguerite’s struggle to tell Rachel what’s on her mind as a sign of embarrassment before basking in the quiet grace conjured. Others will brace for an unenlightened morsel of backhanded and out-of-touch tolerance that never comes before being surprised by what arrives in its place. Either way we find hope in this prevalent divide being erased via heartfelt generosity.

B-

Madre (Mother) – Spain – 19 minutes

A woman (Marta Nieto’s Marta) and her mother (Blanca Apilánez) arrive at the former’s apartment talking about men. Marta speaks about friends, her mother leans into romanticism when the subject of a handsome gentleman comes up, and some jealousy arrives when it’s explained that he’s already attached to someone else. The stakes are thus very low at the start of Rodrigo Sorogoyen’s short film Madre [Mother] — innocuous, every day fodder to create conflict where none exists as a means for intrigue. We are thus allowed to soak in the expensive setting with birch tree columns as the camera pans around corners to keep the whole a one-take affair. Only when the phone rings do we realize there’s something missing and that its absence can prove monumentally devastating.

This lost piece to the puzzle is Marta’s six-year old son Iván (Álvaro Balas) away on vacation with his father. Unfortunately, however, the boy’s dad is nowhere to be found. Iván smartly calls his mother to explain the situation as best he can in the aftermath. They got to the beach only to discover his toys were left in the car. So Dad chooses to get them by leaving his son in the sand to play. Eventually Iván can’t help realizing he’s completely alone with too much time having passed. There’s nobody else in or by the water and no landmarks with which to describe over the phone. All he thinks he knows is that they crossed the border from Spain to France. The rest is anyone’s guess.

What follows is therefore the harrowing experience of a mother desperate to save her child despite having no means with which to do so. Compounding it is the worry on her own mother’s face as the rage and fear takes hold. It’s new school thinking and agitation (Marta screaming on the phone to the police and ready to drive to every French beach in existence) versus old school thinking and calm (Apilánez’s character attempting to soothe her daughter and get her to follow law enforcement’s protocol whether or not circumstances are more direr than that system can handle). One contradiction meets the next until the initial hope that some Good Samaritan will turn up to save Iván gets replaced by the uncertain nightmare trusting a stranger can ultimately create.

Is that sense of futility enough? I’m sure many parents would be quick to say, “Yes.” This scenario has “worst case” heft that will get anyone’s mind racing about what they’d do in a similar situation, allowing the film to be judged on a subjectively emotional level wherein you as the viewer project yourself onto the action. Despite there definitely being merit to that experience, though, I couldn’t help feeling unfulfilled. My mind wanted to figure out why the beach was empty and why the father would leave his child alone. I wanted to know the bigger narrative picture of what’s happening — something Sorogoyen ignores for visceral power. The result is an authentic punch to the gut, but it has nowhere to go. Substance gets ignored for impact.

C+

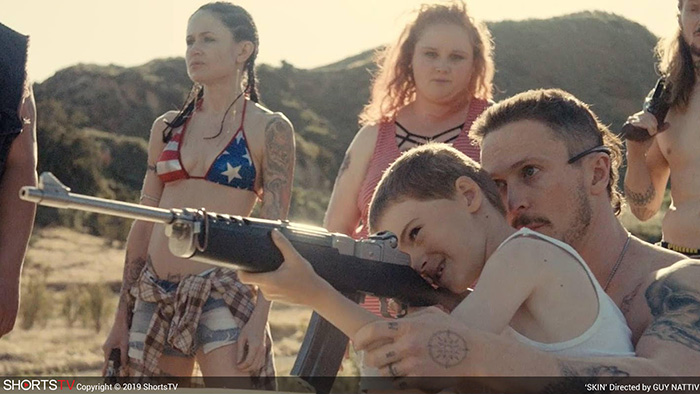

Skin – USA – 20 minutes

How deep does hate go? Is it something with meaning that burns within every cell of your body or a desperate ploy to be included, feel superior, and feign importance? And how much of it is based in fear of the unknown, fear of being exposed, fear of being left behind? Or is it born out of a warped conflation of bigotry with culture and a projection of that which you are onto another in order to trick yourself into believing you aren’t the worthless one? These are the types of questions that allow words that should be synonymous like Nazi, white supremacist, racist, and alt-right to be separated along a fictitious sliding scale. Oh, he’s not racist. He just believes the “best man” should get the job.

This is the messaging at the back of Guy Nattiv’s short film Skin (no relation to his forthcoming feature film of the same name besides Nazi Vikings and casting Danielle Macdonald). He and co-writer Sharon Maymon have crafted their narrative to be less about skin color than the concept of only going “skin deep.” Because that’s as far as the lessons Jeffrey (Jonathan Tucker) teaches his son Troy (Jackson Robert Scott) go. The boy is too young to understand the historical significance of genocide or America First. All he sees is the vitriol his dad, mom (Macdonald’s Christa), and parents’ friends spew upon African Americans. He’s not taught to hate Black people for a reason (because there’s none to give). He’s conditioned by sight. Doing so is “cool.”

And if Dad is willing to beat a Black man (Ashley Thomas’ Jaydee) to an inch of his life in public, that Black man must have been willing to do the same even though he did nothing but give the boy a genuine and reciprocal smile. That’s the knee-jerk reaction in play. That’s what creates a shoot on sight mentality so you never have to allow your enemy the time necessary to become human. So rather than simply beat Jeffrey up as payback, Jaydee’s “gang” decides to unmask the reality of these white supremacist’s so-called power. They seek to use Jeffrey not as a martyr, but an example for how superficial his hate is. This isn’t teaching him about being Black. Their lesson is about dehumanization.

How Nattiv and Maymon pull off that education borders on high concept science fiction in a way that twenty minutes can’t quite pull off without troubles. This is an allegory using real-world issues and thus needs more room to differentiate itself as a heightened parallel. To spring what happens upon us will seem silly to some and thus negate its messaging. For others it will be hard to ignore that Blackness is the method of dehumanization even if it’s Blackness seen through the eyes of a Nazi rather than true Blackness. The differentiation is handled fast and loose so nobody can dismiss that reaction as dishonest. But if you’re able to see past the machinations of the parable, Skin can spark a conversation about our weaponization of fear.

B-

The Oscar Nominated Shorts are in limited theatrical release starting February 8th. See the official site for more details and our reviews of the other shorts sections here.