Originally planned as a directorial debut for Matt Damon, Promised Land was crafted by a story idea from Dave Eggers (Where the Wild Things Are), with Damon co-writing the screenplay alongside John Krasinski. It was a passion project for both of them, but then things got busy, and Damon was forced to call upon a frequent collaborator — Gus Van Sant (Good Will Hunting, Gerry) — to step in and helm the film. Van Sant‘s a fascinating filmmaker, as capable of making bold auteur statements (Elephant) as he is of crafting more down-the-middle dramatic fare (Finding Forrester). So the question with Promised Land became: How much Gus Van Sant would we get in the finished product?

Interestingly — and wisely, if you ask me — Promised Land is no Elephant. It’s a quiet, tempered affair that finds the correct tone early on and, save for a third-act reveal that feels more mechanically unconvincing than anything else in the film, maintains it throughout. The mellow, relaxed opening credits, set against a surprisingly somber Danny Elfman score, provide an authentic introduction to the film’s loving depiction of small-town America. There’s absolutely no replacing the photographic presence of the late Harris Savides, who shot many of Van Sant‘s best films during his storied career, but new lenser Linus Sandgren does an evocative job of capturing the film’s rural locations through a consistently overcast lens, always hinting at the inner sadness at work inside of Damon‘s self-doubting protagonist.

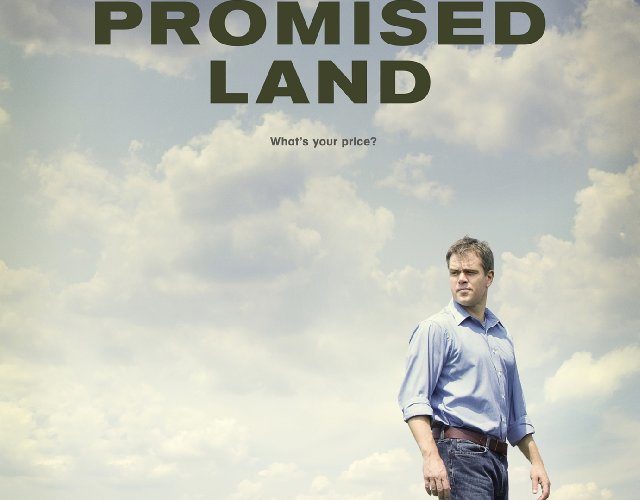

But the film’s never showy. In fact, even though he didn’t end up directing it, Promised Land often resembles what I would imagine a Matt Damon film playing like — confident, composed, organic, restrained. If you look at the recent screen work Damon‘s done — Hereafter, The Adjustment Bureau, Contagion, We Bought a Zoo — there’s a warm, inviting star persona being solidified that favors emotional purity over flashy technique. The character he’s playing here — Steve Butler, a Global Crosspower Solutions representative looking to secure drilling rights to plots of land in a modest town called McKinley — has corporate-guy aspects that are sometimes intentionally condescending, but the film really excels when it zeroes in on Damon‘s performance and the moral crisis he’s communicating to us.

As we learn from the opening scene, Steve has been a highly accomplished employee for Global, and his journey to McKinley isn’t projected to present him with any obstacles. Along with his partner, Sue Thomason (Frances McDormand), Steve is expected to be in and out of McKinley within a couple of days. It’s a poor town, the kind Global has long had success with, and their first day canvasing the territory is filled with nothing but concerned parents that are immediately won over by the financial security these out-of-towners are offering them. The only thing that matters to these McKinley residents is tuition money for their kids, and that’s exactly what Global can give them.

An anti-Global opposition soon starts to brew, however. At a town meeting held at the local high school, science teacher Frank Yates (Hal Holbrook) alerts his fellow McKinley residents to the natural dangers of fracking. Then Dustin Noble (Krasinski), an environmentalist working for Superior Athena, shows up, and he quickly feeds off the combative tension engineered by Yates. Initially a godsend for the people, Global is now a demonized villain, as evidenced by the slew of “Global Go Home!” posters Dustin props up all over town. Steve no longer gets free coffee at the local diner, and the cute schoolteacher (the endearing Rosemarie DeWitt) he had his eye on is now more interested in the communally beloved Dustin. She even invites the guy to her classroom, where he gives her young, naive students a live, fire-filled presentation about how farms get mutilated by corporations.

When the Krasinski character steps in, there is a danger of the film becoming a reductive two-sided fight, but the competitive bickering that ensues actually gives us some revealing looks at Damon‘s character. (Krasinski‘s good-guy reputation, meanwhile, is also experimented with in ways that are at once compelling and contradictory.) Damon and Krasinski have fashioned a nice backstory for Steve — namely, the fact that he too was born and raised in a small farming community — and, in his interactions with many of the McKinley people, we get an almost painful look at a man whose values have been so deeply corroded by the detached world of finance. In a memorable altercation between Damon and an unshaven Scoot McNairy (Killing Them Softly), the contempt Steve shows for McNairy‘s camouflage-colored farmer has a lot of relevant things to say about how a person’s domain can completely warp their principles without them even realizing it.

On the whole, the film illustrates a very perceptive, diverse array of human interaction. For every money-dominated negotiation — the early exchange between Damon and Ken Strunk‘s Gerry Richards is a particularly good example — there is one that’s grounded in earthy resonance. A poignant parallel is drawn between the town’s generational relationships and Sue’s relationship with her own son, which is maintained mostly through the electronic window of Skype. She can only learn of her son’s blooming baseball career through her laptop, and we get a melancholy beat later on when she stands watching a neighborhood McKinley game, and there are prominent Global logos pasted on the jerseys of the competing toddlers.

The film excels in moments like these, where minor, everyday gestures are used to reflect larger, more important issues. This is why the film’s conclusion is so disappointingly preachy. Not only does it hammer home a theme the film was already making in subtler ways, but it feels as if it’s forcing the film onto a much larger scale than it was previously aiming for. There is obvious contemporary relevance in the film’s premise, but part of the calm pleasure of Promised Land resides in the fact that it generally addresses those topics without overtly exclaiming them. The ending does away with that approach entirely, twisting Damon‘s Steve into a message-carrying symbol, as opposed to the well-defined individual he is for most of the film.

If the film concludes itself on an ill-conceived note, though, it’s still full of laid-back satisfaction and small-town knowledge that ripples with verisimilitude. At the end of the film’s first town-wide gathering, during which Holbrook‘s objections cause quite a stir, the high school basketball team trots out onto the court and starts performing drills while Steve is still standing there, stunned by the hostility that has suddenly greeted him. It’s a wonderful instance of acute observation: What better way to highlight Damon‘s uncertainty than to shove a bunch of basketball players in his way, none of whom give a moment’s notice to his situation? It’s details like this — details which enlighten both character and atmosphere — that Promised Land does best.

Promised Land will begin a limited release on December 28th, and is scheduled to expand on January 4th.