Miranda Fall (Mireille Enos) is a cataloger. Her art leads her on journeys following new subjects in order to understand who each is by what each does and possesses. She voyeuristically captures their lives in photographs and objects, exhibiting her findings as though a celebration despite some of her targets believing it more akin to a memoriam. And why shouldn’t they? Miranda is ostensibly stealing their identities for public consumption and in turn private financial compensation. She uses the mundane routines and patterns of others to provide a distraction from her own and the fame and fortune allowing her excitement and material gains they could never afford themselves. Is she therefore cataloging these strangers or merely cataloging what she needs from them to satisfy her own selfish purposes?

It’s an interesting question to ask of all artists who create in the hopes of a sustainable life. How much of their art is a piece of them and how much a calculated — wittingly or not — product meant to appeal to the masses? We can get into concepts of benefactors (whether collectors, galleries, or dealers), art for art’s sake, selling out, and posthumous praise that comes from a place far removed from the artist him/herself. We could spend days debating the merits, lies, and beliefs of each without getting anywhere. Everyone has an opinion about what art even is (advertising, packaging, acting, etc.) that clouds their ability to listen, evolve, or argue so minds can learn and perhaps change. So writer/director Camille Thoman decides to incite us all.

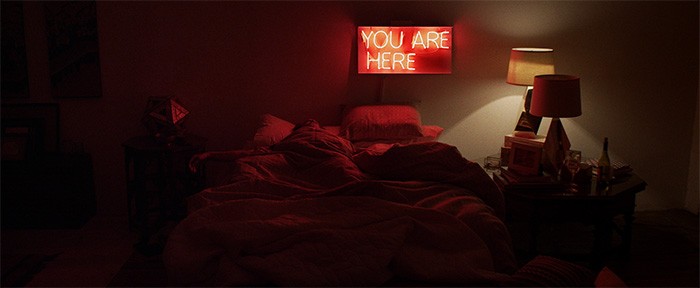

She gives birth to the lightning rod that is Miranda — an artist with very strong ideological boundaries to both grant her the permission to claim ownership of what’s not hers and distance herself from those she’s exploited if or when they should voice their displeasure. This character exists as a character, a manufactured façade that lets reporters (Nina Arianda’s Margaret Lockwood) into her home because it too is an extension of Miranda the public figure rather than Miranda the hard-working, creative orphan turned celebrity behind the noise. While those she chases have an authenticity she’s right to commend and aspire to honor, she’s a hollow vessel beholden to “arrangements” instead of relationships. So caught up in those worthy of her gaze, she’s lost her true self.

The title Never Here is therefore a direct commentary on Miranda forever hidden behind her lens. She’s so adamant about capturing “self” immortalized in 1s and 0s via technological advancement that she’s ceased seeing the world without it. Everything is a mystery to be solved; every person a pawn set in motion along an immovable track devoid of deviations. She watches rather than lives, following rather than leading. As such, she freezes the first time that lens turns to look back. Suddenly she realizes the gravity of her actions and her very existence. She becomes the star of a criminal investigation with all eyes pointed her way. What did she see? Who does she know? What has she neglected to say? It’s no longer possible to hide.

Unlike those in her art, however, Miranda volunteers. After having sex with a married man (Sam Shepard’s Paul Stark), she leaves the bedroom as he answers her phone. He witnesses a violent attack while standing by the window, the perpetrator looking straight at him upon hearing his yells to stop. As quick as it happens, all evidence disappears. The victim and assailant are gone, but the incident must be reported regardless. Paul should be the one calling, but he can’t. Doing so asks why he was at Miranda’s so late. So she makes his statement her own. She places a new identity onto herself, filtering primary sources through her eyes to create this fictional character. She does to herself what she’s made a living doing to others.

How would you feel if someone put your life on display without your knowledge or permission? You’d feel violated. Hate. Paranoia. Why wouldn’t you start looking over your shoulder, wondering if someone else was doing the same thing? Every museum patron now knows your face, your home, and the places you frequent. Miranda places an unwanted burden upon her subjects in a way that explains why releases are required to use someone’s likeness when they haven’t implicitly signed that right away with the purchase of a concert or sporting event ticket. And now she knows how it feels. Now she must fear this unknown predator who knows where she lives and Paul’s face. She acknowledges her enemies. She experiences changes in routine with newfound clarity and unearned meaning.

Thoman spins a suspense thriller with all its genre underpinnings around Miranda to take the control she’s always carefully ensured was hers away. Maybe her old college flame and current police detective Andy (Vincent Piazza) or another on the force has caught the perpetrator. Maybe he was a stranger or maybe someone she’s met. Maybe she knows the victim too, the coincidences she once reveled in now rendered as nightmarish fate. Maybe this man she cannot stop thinking about — a new subject for a new art project — is involved. So while she does play amateur sleuth, the irony that she wasn’t the one who saw the real criminal’s face to compare isn’t lost on her or us. In this way “S” (Goran Visnjic) is simultaneously monster and prey.

Think about it. His being in her proximity to keep her camera going is just as likely her being in his. Who follows who when there’s a very real possibility both parties are aware of their stalker? Anxiety sets in until Miranda is left questioning those aforementioned boundaries. Yes she should be okay with someone doing to her what she does to others, but when is the line between innocent surveillance and explicit threat crossed? Is there even such a thing as “innocent” spying? Miranda starts projecting guilt or suffering onto everyone she comes into contact with because she feels both in equal measure too. She projects horrors where none exist and Thoman complies by keeping us off-balanced with visual cues and impossibilities forcing us to question reality.

She films Visnjic’s “S” as creepy and yet harmless, his broad clown-like expressions filling us with despair when another context would conjure joyous frivolity. Thoman changes the second-hand sourced sketch of the initial assault’s culprit so that it resembles one character and then another, a fluid gender giving pause as far as whom Paul even saw. We begin to recall what we’ve seen and know thanks to the constant display of arrows and cryptic words blurring the line between real and fantasy until we realize Miranda simply left the bedroom that night. Who’s to say she didn’t go outside and attack someone? Who’s to say Paul’s affection didn’t alter his vision from comprehending that truth? And once events begin folding in on themselves, our own eyes prove forfeit.

Never Here hits limited release on Friday, October 20th.