If, within art cinema, there comes the instant gravitation to less the film than the name — the all-powerful auteur that supposedly doesn’t have to bow down to corporate masters — then even with a film as immediately striking as 1976’s Insiang, we begin with its author, Lino Brocka. Even in a life cut tragically short, he left enough of a mark to still be considered the Philippines’ greatest filmmaker, amongst his laurels being the nation’s first director to play in competition at Cannes. A particular association made with him was an outspoken criticism of the Philippines’ dictator-in-chief, Ferdinand Marcos.

But carrying that expectation over to Insiang, even without one mention of Marcos’ name throughout the film, the presence of both a fundamentally rotten authority and people left to fend for themselves in poverty leans a viewer, even the uninformed, towards assuming a greater institutional critique. Yet to quickly sum up its political relevance brings to mind what Nick Pinkerton noted in his piece on the poliziotteschi genre a couple of years ago — how film critics tend to have the inclination to assume an all-knowing historical perspective, as if regurgitating “research” from various Wikipedia pages instantly gives us a complete understanding of a work’s place in time. In the case of Brocka’s film, being the recipient of a new digital restoration — and thus given somewhat of a moment in the spotlight — the urge to locate the reason, so to speak, behind its fervor runs high. Though perhaps that comes in simply illuminating its merits.

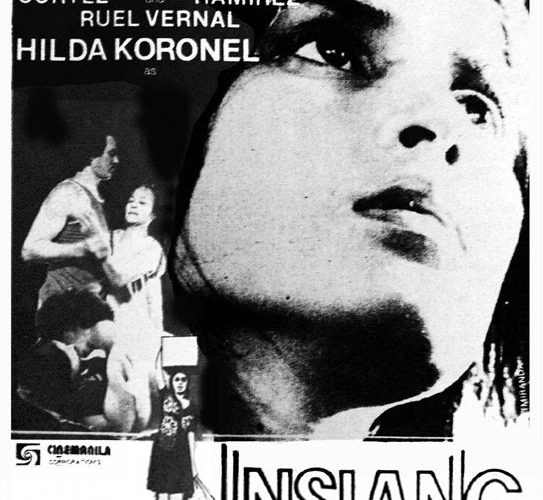

At a lean 95 minutes, the film manages to shift multiple perspectives within its ensemble, all anchored by the titular Insiang (Hilda Koronel), an exceptionally beautiful 17-year-old girl tended over by her distracted single mother, Tanya (Mona Lisa), who’s still bitter from being abandoned by her husband and Insiang’s father. Tanya takes in a new lover, Dado (Ruel Vernal), a much younger street thug. It doesn’t take long for him to turn his attention to Insiang, resulting in her rape. Finding no solace in others — or, rather, ultimately facing an indifferent justice system (earlier in the film, another attempted assault from one of her siblings is brushed off — she has to turn to her own form of martial law, thought to which isn’t exactly a simple process of revenge.

This fraught atmosphere extends to the streets and neighbors; eyes peering from windows — everyone’s a voyeur to others’ misery, as if to relieve themselves from their own — including from a fellow teen with a crush on Insiang but none of the courage to speak to her. But the boy’s counter — and Insiang’s beau, the dim-witted Bebot (Rez Cortez), who is prone to uncomfortably feeling her up at the cinema — only lets her down when she turns to him after her traumatic experience.

Being located in the bustling streets of a Filipino slum and not heading anywhere near an uplifting humanist outcome, Brocka’s film could be branded with the dirtiest words within Third World cinema: “poverty porn” or “miserabilism.” But the trick up Brocka’s sleeve is in not shying away from a genre-play; creating as much a heated, violent melodrama as, say, Anthony Mann’s The Furies. Of course, melodrama is not chained to Hollywood; Rossellini’s films starring Ingrid Bergman managed to bond realism with heightened emotions and narrative beats.

Yet Brocka’s blunt-force begins to border on another genre, as evidenced in its opening scene, which presents not the film’s titular character, but rather the image and sounds of pigs being gutted in an abattoir — a slaughterhouse brutality that instantly recalls Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre from only two years prior. It’s with this that Insiang takes something of a place within ’70s exploitation cinema, or rather the particularly nasty sub-genre known as the rape-revenge picture (key titles being I Spit On Your Grave and The Last House on the Left). These are films that didn’t shy away from excessive violence against women nor the retaliating gesture of castration, certainly operating on an unhinged moral compass.

It initially seems strange to place Insiang within this genre. The easy binary is that Third World cinema uses realism as both a counter to glossy mainstream films and as to capture “Life The Way It Is,” while exploitation films’ grittier means are simply all they have at their disposal for the sake of sensationalism. Holding the film to a certain expectation — being that it uses a specific, or rather marginalized milieu — it’s still not hard to see Brocka reconfiguring “reality” rather than just capturing it; it’s rough, but not necessarily raw, for every image and rhythm feels perfectly calibrated.

Moreso, it isn’t interested in a simple pain-and-recovery narrative or as a feminist work, as, after all, Tanya comes off as second to Dado as the most despicable character in the film, blaming Insiang for her own assault. It’s from here that the complicated morality becomes most set: one generation damned to being a victim of the past’s mistakes. It ends in blood, the already fractured institution of family only facing another apocalypse-of-sorts. Forty years removed from this film, what transcends a fixed point of socio-political interest is the eternal howl into the night.

Insiang will screen on Sunday, April 10 at the TIFF Bell Lightbox as part of their “Restored!” series, which also includes Jeanne Dielman, A Touch of Zen, Late Spring and others.