Since the start of the millennium, Ti West has been pigeonholed as a horror director, but even from the beginning, his interest in the genre moved far beyond creative kills or well-engineered jump scares. Horror was a vehicle for more mundane themes. Even his craziest films like The House of the Devil and The Sacrament had a root in relatable humanity. For the lead of The House of the Devil, the plot’s just a result of a bad night where she needed money for rent, and in The Sacrament, the violent behavior of the cult is secondary to a portrait of the exploited.

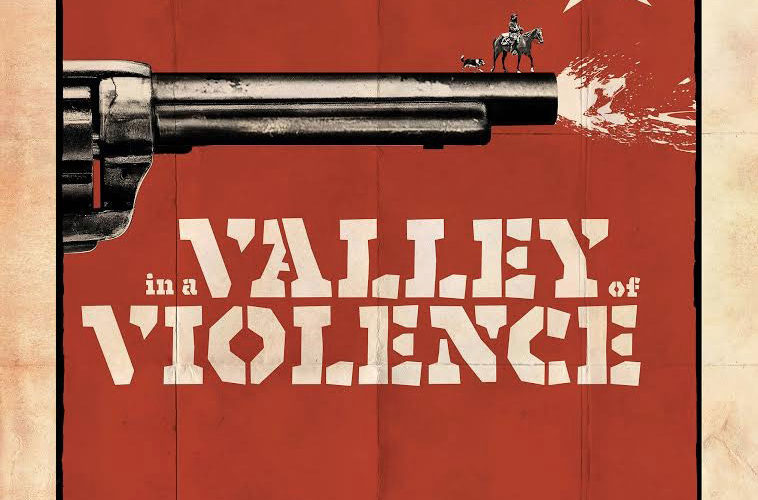

West’s latest, In a Valley of Violence, is a revenge western in the vein of subversive genre fare from the likes of Sergio Leone or Sam Peckinpah. However, while the formidable director has never had a more high-profile cast or a more dynamic backdrop for compositions, the film only plays lip service to West’s history of genre subversion.

Accompanied by the most adorable dog in the world, Paul (Ethan Hawke) is a classic western figure – a man with a checkered past, good intentions and a killer quickdraw. But the old west doesn’t allow peace. And even one-horse-towns like Denton are dominated by small fish sinners who spend their days in pissing contests with strangers.

Gilly (James Ransome) is one of these small-time bullies, a twitchy motormouth who doesn’t know when to close his mouth, let alone when to holster his gun. Paul’s just passing through, but he makes a mark with Mary Anne (Taissa Farmiga), a puckish teen with a thirst for drama, and Gilly, who’s become feared in the town for his hair-trigger temper.

It’s only a short time before Paul’s cracked Gilly’s noggin, and pushed the story into high-gear. Gilly and his crew of creeps are far out of their depth, but they’re not just willing to suck up their pride, and mosey on. Gilly’s papa, the one-legged marshall of the town (John Travolta), won’t stand for this violence either, running Paul out of town, and setting into motion the rest of the film.

In a Valley of Violence is easily the most conventional of West’s career, as it not only follows a traditional progression, but also feels far less concerned with spontaneity or the mediation of its own message. At first, it’s refreshing to see West work within Hollywood’s strictures, but it’s also deflating to see him pushing towards instead of against tired genre tropes like sidelined women characters, and unmotivated bloodlust.

West’s slow-burn direction remains singular with sequences that are often thematically difficult to watch, but always visually engaging. But even as West shows obvious fondness for the spectrum of the western genre from classicists like Howard Hawks to midnight movie-friendly splatterfests, he just doesn’t have the writing facilities to make the anachronistic dialogue convincing, or push rote archetypes beyond their one-dimensional understanding.

Mary Anne is saddled with the most clumsy dialogue in her relationship with Ellen (Karen Gillan), her bratty southern belle sister. Written in a screwball-style repartee that feels totally out of sync with the film around them, their dialogue is consistently unfunny, and often irritating.

Occasionally, the subtextual dialogue finds a place of intersection with the rest of the film such as an extended rant from a dispensable character about how he’s offended by his nickname, or a showdown near the climax that’s a single-scene distillation of West’s entire warped sensibility, but in general, it’s a reminder of the levels of artifice. Hawke, in particular, feels lost at sea here. In the right hands, he’s a sturdy anchor, bringing a lived-in desperation and searing sincerity, but it’s hard to take him seriously as he’s forced into “Man With No Name” catchphrases like, “Tell the devil I’m going to Mexico.”

Travolta sounds most at home with the dialogue, bringing a rugged assurance to his character, while also immediately recognizing that he’s out of his depth with someone like Paul. His delivery borders on hammy in all the right ways, as he chastises his fellow deputies for their relentless stupidity.

Once In a Valley of Violence really starts moving, West has an expectedly strong eye for bitterly funny action set pieces. At times, the violence plays like a version of a more comedically pitched version of Last House on the Left spliced with the rhythms of more traditional western shootouts. In a Valley of Violence feigns to be a revisionist western, but it’s frustratingly stuck in a place of inevitability in the last half. It’s an excellently-made imitation, but coming from a director whose made a career of tilting the familiar, it’s a disappointing detour.

In a Valley of Violence screened at the The Chicago Critics Film Festival and will be released by Focus World on October 21.