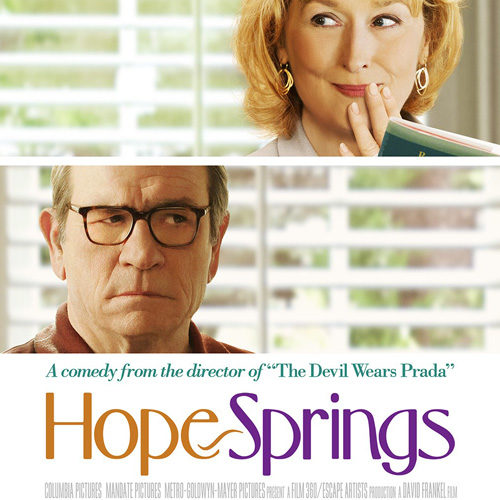

I can’t tell you how gratifying it is to see Meryl Streep in a role like this. As immaculately convincing as she can be when called upon to step into the shoes of a larger-than-life figure, there is something calm and savory about the experience of watching her finesse her way through a character that could be your next-door neighbor. And that’s exactly who Kay Soames (Streep) is — the feminine half of a 31-year-old marriage that slides by on tension-avoiding routine, all the while failing to give us even the slightest glimpse of the glitter that forced these people to fall in love during their college days.

Her husband is Arnold (Tommy Lee Jones), and it’s another assignment that plays somewhat against the recent personality of the performer. Lately, Jones has been brooding himself to death in flicks like No Country for Old Men and In the Valley of Elah, but here, placed within the comedic-dramatic realm of director David Frankel (The Devil Wears Prada) and screenwriter Vanessa Taylor, he needs to be lighter, spunkier and more agile. And he comes through.

That’s not meant to imply, however, that Jones’s weathered gloominess is gone completely. On the contrary, one of the main reasons Arnold and Kay’s marriage is deteriorating is that Arnold attends to life with a forlorn distance, treating every obstacle of his day — including his unhappy wife — as yet another object separating himself from the relaxation of falling asleep to the training-session banter of the Golf Channel.

And, to make it even worse, the moments when Arnold does come out of his shell and show some passion are characterized mostly by anger, as opposed to more productive kinds of excitement, like romance. This is a fact pointed out to him on multiple occasions by Dr. Bernie Feld (Steve Carell), a well-dressed relationship counselor who catches Kay’s eye on the cover of a book at the local Barnes & Noble. Bernie’s intensive, week-long therapy session requires the couple to take a trip up to Maine, and, in an amusing bit of bickering-couple humor, Kay’s unwillingness to negotiate winds up being enough to get the ever-reluctant Arnold to agree to the trip.

Carell plays his character with a straightforwardness that’s almost jarring. We develop little, if any, notion of what Bernie is like out of the office, and Carell, through his candid advising, clearly shows no interest in such things. I’m worried some viewers will take that as a negative, expecting Carell to be a playful supporting-player highlight, and then being disappointed when he turns out to be the opposite. Personally, his choices felt consistently shrewd, keeping the focus where it should be — on Jones and Streep — while also embodying the role of therapist with more authenticity (and less forced charisma) than you’d find in most mainstream American films of this variety.

There are ways in which the movie could be better, of course. Some scenes end at the precise beat you want to propel the scene forward, and some of the methods through which Arnold and Kay interact with people other than themselves have the stench of tacked-on structural oversight, like when Arnold buys Kay flowers after overhearing a direct testimony of a co-worker, or when Kay escapes her husband’s anti-discussion wrath by becoming instant BFFs with a bartender (Elisabeth Shue), who likes to give out white wine for free.

But there’s too much right in Hope Springs to simply discard it as another fluffy coming-of-age tale, old people-style. Unlike John Madden’s The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel, Hope Springs doesn’t decide to explore an engaging storyline by surrounding it with a half-dozen uninteresting ones, and when the film’s don’t-leave-just-yet end-credits begin to roll, we’re surprised by how delicately deep our understanding of these two people has become. We want them every bit as much as they’re fighting to want each other.

Hope Springs is now in wide release.