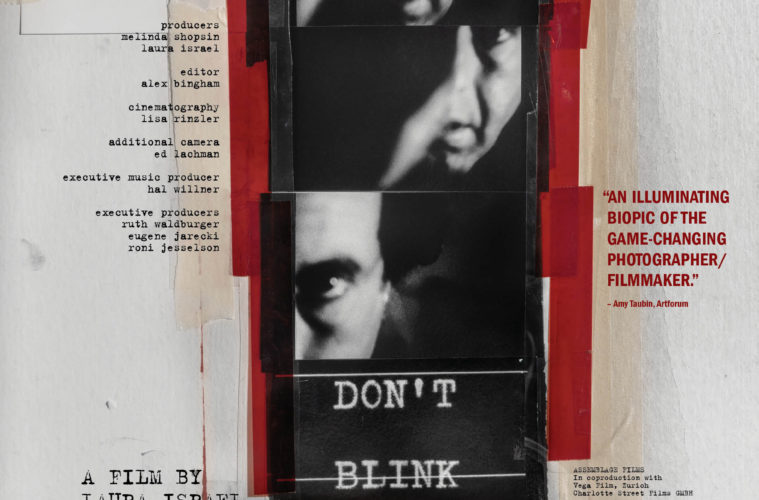

Few people are living embodiments of their style. Now that David Bowie and Prince have left us in the same year, even fewer are. Robert Frank, the subject of Laura Israel‘s documentary Don’t Blink – Robert Frank, and his art — striking photographs and film of Americana — reflect one another like those collages of dog owners and their pets. Rather than both having droopy ears or a snooty nose, they crunch like shards of glass beneath boots. Frank and his creations grind against good taste while still being sharp and beautiful. His is an imperfect America, as if Norman Rockwell subjects stepped out of frame for a few drinks and a game of dice, then got lost on their way back home.

Frank is best-known for his 1958 photography collection The Americans, which recorded the photographer’s explorations of social and economic struggle. A documentary about this kind of artist has the reflexive task of capturing a man who has captured America. It does so by putting him back into his work. At 91, Frank acts as a tour guide for his life’s portfolio. We appreciate his widely-respected short film Pull My Daisy, narrated by Jack Kerouac, for its raw edges in the way we appreciate the man himself for good-natured shabbiness. Frank rode the tide of art movements (like the rambling Beats that collaborated on Pull My Daisy) by maintaining his good-humored notions about creation. His photographs imitate his influences, notably the newsreels that the Swiss immigrant watched when he moved to New York, and, in turn, influenced his life.

A man in love with his own aesthetic, Frank moved into a house in Nova Scotia as austere and lovely as one of his photographs. His scratching and dirty-captioning of his film negatives and other experimental techniques add an itching soulfulness to his work, a constant reminder that the photograph shows more about the photographer than its subject. Every room Frank inhabits seems a bit more rumpled, every car he drives a bit closer to the scrapyard. Shot in black-and-white, except for color archival footage, Don’t Blink visually equates the photographer and the work. His are photographs of tense peace, threatening to shatter at a moment’s notice. As more and more of Frank’s life peeks through, so deepens our appreciation. The film doesn’t shove its photo slideshows against lazy, grungy, bluesy tunes to inflect a hopeful melancholy, but to amplify that which already exists within them.

Frank’s triumphs and tragedies are captured through his work. His marriage and young love bursts from each frame, all smiling faces and shy adoration, while the early losses of his children, either by accident or suicide, are memorialized in frosty landscapes. That the film remains so spritely despite the turning hand of fate mimics the artist’s response. Don’t Blink becomes a quick, poignant, funny manifestation of its subject’s ethic. The aging artist looks back on his life, whether it moved with or against him, and filters it all through work and friends made.

Don’t Blink is the rare documentary both vague enough to whet your appetite and specific enough to imbue a sense of kinship with its subject, like an old friend from camp you haven’t seen in decades. Like Frank himself, the film chugs ever forward as an elaborate, chaotic, grumpy, optimistic mess. His paradise exists in the ordinary foibles of a mailman on a long route or the graffitied corner of a dilapidated building next to the train tracks. The film’s paradise exists in Frank delighting in these memories. Simplicity shaded with a special tint — a tint that looks sorrowful or joyous depending on the light. The end result is an unapologetically enthusiastic, excited, and earthy celebration of artistic creation and the life that makes it inevitable.

Don’t Blink – Robert Frank enters a limited release on Wednesday, July 13 at Film Forum, and will expand in coming weeks and months.