In a world defined by rapid-fire news tweeting, instant social networking and Internet overload, how do we unplug? Beyond that, do we even want to? This is the obvious-but-persistent concern behind Disconnect, a multi-narrative string of intersecting lives that highlights our tech-obsessed culture and the lurking dangers of immersion at the cost of interpersonal identity.

A few years too late to be relevant and a bit too forceful and didactic to be thought-provoking, this Crash for the Facebook generation spins its cautionary gears without really working us up. Fans of of threaded storytelling may overlook the rehashing of familiar themes because of the strong performances of the cast, who sell us these people and their problems with a real heart-sick gusto. If he does nothing else, director Henry Alex Rubin inspires a look into the mirror of our own online habits by evoking the perils of getting caught up and lost in a world that exists as much in cyberspace as it does anywhere else.

The illusion of relationship and proximity is one of social media’s biggest lures, and accounts for the way in which a large portion of the world can feel like they lost an uncle in Roger Ebert, or communally share grief and shock at tragedies like Aurora, all while participating in universal befuddlement at the Honey Boo Boo clan. Somewhere in that happy land of Instant Messenger hugs and Facebook likes there are the dark fissures Rubin explores; identity theft, chatroom infidelity, cyber-bullying and web-cam eroticism.

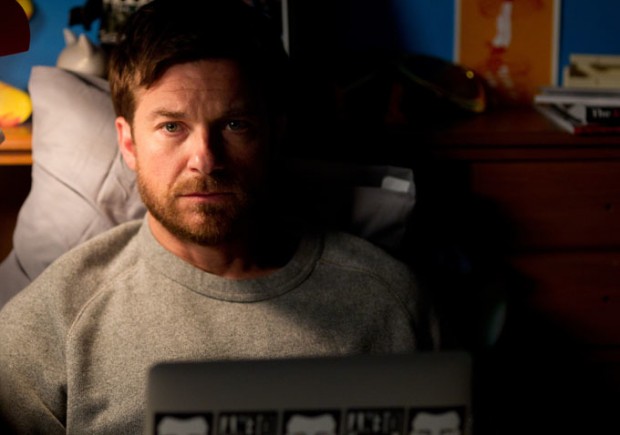

Rubin and his writer Andrew Stern have conceived a triptych of scenarios featuring people who all behave in inherently stupid ways, mostly because they can’t see the forest for the digital trees. Jason Bateman and Hope Davis, the two biggest names in the cast, play the distracted and distant parents of Jonah Bobo’s persecuted music geek, who gets maliciously pranked by a couple of skater punks and finds his privates pasted all over the internet and shared at school. One of those kids, Jason, feels remorse for his actions and incidentally has a computer crimes detective for a dad (Frank Grillo). Grillo’s ex-cop turned cyber-sleuth is currently working for two married clients (Alexander Skarsgård and Paula Patton) who recently lost their infant son, and shortly after their bank accounts and financial future, the latter likely as a result of the wife’s dubious online ‘friendships.’ A little less close to home is Andrea Riseborough’s tv reporter who ends up in intimate proximity to Max Thieriot’s teen runaway who works as an online porn performer.

Lining all of these stories up so they coalesce into a portrait of private sanctity sacrificed for technological escape isn’t an easy proposition and that Rubin succeeds in translating all this Lifetime portmanteau into palatable drama is commendable, particularly since this is his first narrative feature. There are some definitive and deeply poignant beats in Disconnect, many of them concerning Bobo’s fearless portrait of Ben, the one character who’s the most innocent in terms of culpability but also the most gullible, suffering only because he’s naïve of the world he’s been born into. When Bateman’s lawyer must wake from his fugue and confront what’s been done to his son, it’s the actor’s best work to date. He’s an everyman who should have seen more, earlier, but how often have we thought the same of ourselves after being blinsided by cumulative neglect?

Patton and Skarsgard are serviceable but watching their marriage strengthen as a result of a lesser adversity than the one that drove them apart is never less than interesting. Part of that is down to Grillo as the detective, who may be the moral heartbeat of Disconnect. Through his eyes we see the film this could have become had he been the anchoring character. Thieriot is grating as the sleazy web-cam model but that’s obviously intentional. His story with Riseborough is the albatross around the film’s neck; it isn’t necessary, and the more theatrical it becomes the less it seems to say. When all of these threads arrive at violent or incendiary conclusions, Disconnect itself becomes another symptom of the culture it critiques. The medium has transformed since Altman’s Shortcuts, and the internet and its never-ceasing strands of life narrative have no doubt influenced the likes of Crash, Babel and now Disconnect, whose de-saturated cinematography and ambient score resemble a pastiche of indie shorts that might have played on the Atom network back in 2004.

As a piece of hand-wringing emotional cinema, I’d be lying if I said Disconnect didn’t achieve what it sets out to do and then some. I only wish it were able to address its social concerns with a bit more complexity and nuance. I’m obviously no Luddite, but it doesn’t take a two-hour film to convince me that there aren’t dangers and pitfalls inherent in the virtual freedom we have arrived at. We have come a long way in a very short period of time, and the responsibility and wisdom required to properly navigate haven’t necessarily advanced at the same rate. This is essentially the gist of Disconnect; technology is not a Faustian demon bartering for our soul but it does open new doors for that oldest devil of them all, simple human nature.

Disconnect is now in limited release.