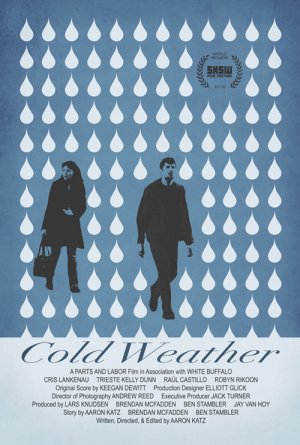

Mumblecore goes mainstream, or somewhat so, in Cold Weather, writer/director/editor Aaron Katz‘s second feature film. His first, Quiet City, helped spark what’s now cautiously viewed as a micro-budget film movement, usually involving a lot of improvisation and shaky-cam cinematography.

Cold Weather is some of that and a whole lot more. Doug (Cris Lankenau) returns home to Portland a college drop-out in need of a job. He studied forensic science in school. So, naturally, he finds work at an ice factory, moves in with his sister (Trieste Kelly Dunn), makes a new friend in a co-worker named Carlos (Raúl Castillo) and meets up with his ex-girlfriend Rachel (Robyn Rikoon), who’s back in town for a few days. Then, all of a sudden, Rachel’s nowhere to be found.

Conflict! Let the mystery begin. Doug, at first apprehensive, is brought out of his latent-forensic shell via Carlos, who’s a worry-wart. Pretty soon the two friends are Sherlock and Watson, discovering clues both skillfully and haphazardly around the hotel where Rachel was last seen. Between each scene Katz and his cinematographer, Andrew Reed, take a breath and showcase the Oregon landscape their characters are surrounded by. At first it may be jarring, but soon becomes another assured beat of the whole narrative.

As for the mystery, well, it never gets too exciting. There are codes to be broken and foot chases to be had, but there’s certainly not enough money on display to make any of it look entertaining. But then that’s the charm of it all. Katz puts very real people into very extraordinary situations, but instead of those people rising to the occasion, the occasion turns out to be pretty regular; the kind of thing that sounds much cooler talking about at parties, rather than actually experiencing.

There’s a laconic confidence to the filmmaking here that pushes the narrative through some soft points, most specifically one scene in which Doug and his sister sit at a bar for an extended period of time contemplating the next move. It runs on for a long while far too late in the film and runs out of steam, but the chemistry between the two siblings and the patient camera keep the viewer interested.

This is a nice, relatable film wound up in a genre few people don’t enjoy. It’s also a step forward for Katz both as writer and director, promising more from both himself and the Mumblecore movement he helped bring to life.