Following The Film Stage’s collective top 50 films of 2024, as part of our year-end coverage, our contributors are sharing their personal top 10 lists.

As always, what is considered best is first determined by what can be seen, and this year there were many films that I missed. When it came to popular releases, for example, some took too long to be released in the UK (Hard Truths, Queer, The Brutalist, Nosferatu, Juror #2); some were showing while I was reviewing other films (Rumours, The Seed of the Sacred Fig, I’m Still Here); and others just simply passed me by (I Saw the TV Glow, Dune: Part II, Gladiator II). And the same problems were even more pronounced when it came to watching short/experimental films. Nevertheless, there was much that I enjoyed this year, and several films that did not make the final cut might well do so if I were to make the list again at a later date. I hope that my current selection will point you towards something informative and/or entertaining, and that it will add, if only in a small way, to the voices of dissent around the world struggling against oppressive regimes and private tyrannies.

Honorable mentions: The Shadowless Tower, The Miu Miu Affair, Only the River Flows, Nickel Boys, All We Imagine As Light

10. Witches (Elizabeth Sankey)

Elizabeth Sankey’s personal account of post-natal depression and post-natal psychosis serves as a starting point for a fascinating study of gender roles, witchcraft, and the ‘covens’ of women throughout history who have striven to support those whom male-dominated society would sooner ignore, malign, or kill. With the increasing privatization of the NHS in the UK, and the subsequent decrease in quality of care, Witches is an inspiring call to action, but also a sad reminder of just how broken the British healthcare system really is.

9. Anora (Sean Baker)

When people say ‘cine-poetics,’ they usually mean controlled movements and rhythmic continuities, a general elegance and refinement of sensibility. They rarely mean a group of shallow, vindictive characters who scream at one another non-stop and use the word ‘fuck’ like it’s going out of fashion. And yet, in the right hands, these qualities can be just as poetic as the relatively sedate cinema of, say, Ozu or Tarkovsky. Such is the case with Sean Baker’s Anora, which constantly transforms its grammar of impoliteness into a poetry of conflict in the manner of Eisenstein and Dovzhenko, with the key difference being that Baker’s montage is essentially verbal, rather than visual, in nature. A rare Best Picture contender of genuine merit.

8. Close Your Eyes (Víctor Erice)

Films about the power of cinema are rarely powerful films themselves, but Víctor Erice’s Close Your Eyes is a marked exception. Like my favorite film of last year, Laura Citarella’s Trenque Lauquen, Close Your Eyes is not only a mystery in the ordinary sense of someone going missing (here, a beloved actor, Julio Arenas, who disappears mid-shoot), but also a mystery of atmospheres in which the vague, nameless tones between genres are explored in all their beauty and authenticity.

7. Coma (Bertrand Bonello)

Although Coma premiered at the Berlin Film Festival in 2022, it has taken two years for it to receive theater distribution in the United States, and so qualifies for TFS’s end-of-year features (it ranked at #30 in our Top 50). Undoubtedly the best film to emerge from the pandemic, Bonello’s low-budget masterpiece not only captures the eerie seclusion of that period but also its dark, often ugly, subcurrents. The problem on Bonello’s mind is a kind of modern crisis of faith, a loss of confidence in the capacity for ordinary people to bring about solutions to climate change, extremism, etc. As the titular Patricia Coma puts it, “What can we expect of modernity when all that awaits us is survival?” Bonello’s articulation of the question is nothing short of astounding, even if his answer is largely incoherent.

6. The Beast (Bertrand Bonello)

In The Beast, Bertrand Bonello uses Henry James’ original story not so much as a text to adapt as a starting point from which the histories of various sexual, cultural, and existential anxieties are traced and examined. Predictably, most major reviews of the film failed to mention any of these histories, focusing instead on the general zeitgeistiness of the film’s allusions to AI and incel culture. But, as repeated viewings bear out, the major discourse within The Beast is less concerned with specific instances of social conflict than with the patterns and developments of such conflicts over time.

5. It’s Not Me (Leos Carax)

Leos Carax’s It’s Not Me is both a dazzlingly entertaining autobiography and a touching homage to Carax’s friend and mentor, the late Jean-Luc Godard. What begins as an answer to the question “Who is Leos Carax?” quickly turns into a highly discursive commentary on the inseparability of biography and fiction, the metonymy of the photographic image, and the ambiguous, fragmentary nature of the idea of the artist. On the latter point, It’s Not Me stands as the natural conclusion to the auteurist conception of filmmaking that Godard and others posited in the late 1950s: namely, that directors are just as much products of their films as their films are products of them.

4. Chronicles of a Wandering Saint (Tomás Gómez Bustillo)

Argentine filmmakers have arguably been some of the most vital and creative voices in cinema in recent years—particularly the El Pampero Cine collective, comprising Laura Citarella, Mariano Llinás, Agustín Mendilaharzu, and Alejo Moguillansky—and Tomás Gómez Bustillo’s Chronicles of a Wandering Saint represents the very best of that tradition in 2024. In addition to some beautiful set design and two inspired performances by Mónica Villa and Horacio Marassi, the film brims with nuanced, empathetic, and frequently hilarious looks at religious faith, life after death, marriage in old age, and the trivialities of hypostatic union. Easily my choice for debut feature of the year.

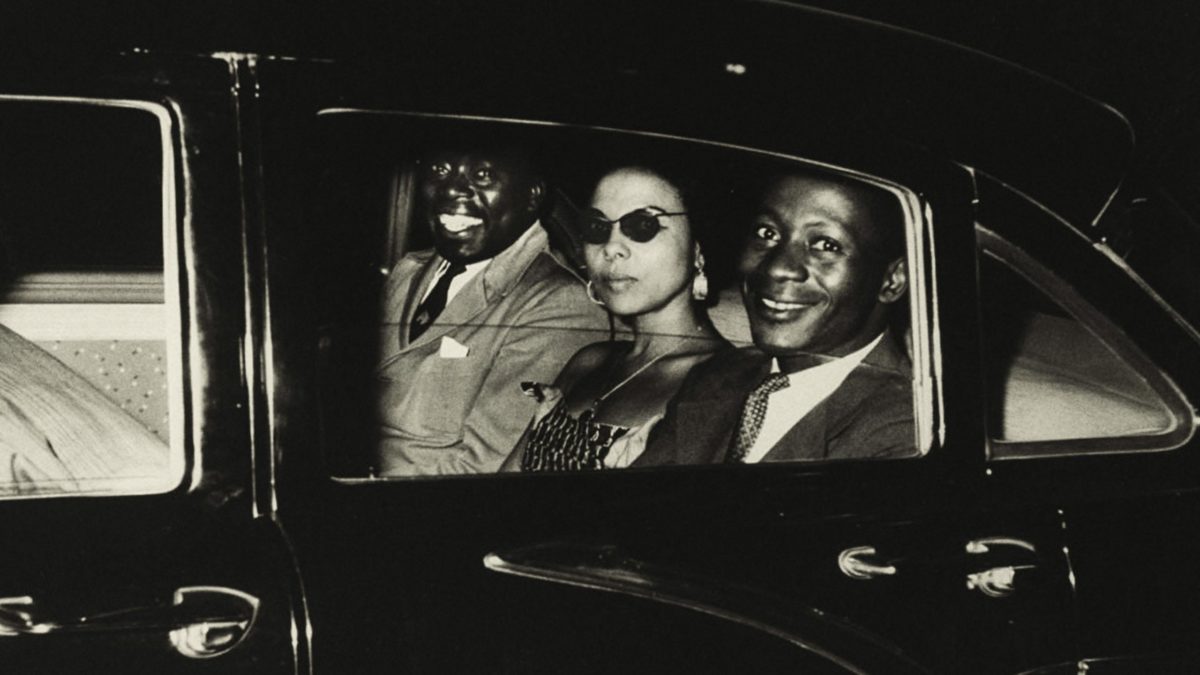

3. Soundtrack to a Coup d’État (Johan Grimonprez)

Soundtrack to a Coup d’État is a blow-by-blow account of US plots in the 1950s and ’60s to maintain control of key uranium reserves in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, undermine growing support for a United States of Africa, and, with the help of British and Belgian authorities, murder the Congo’s first democratically elected president, Patrice Lumumba, in 1961. The editing style—which takes inspiration from the CIA’s use of jazz icons such as Louis Armstrong and Dizzy Gillespie as smokescreens for their terrorism—is bold and freewheeling, mimicking the flow and syncopation of the soundtrack to great effect. A superb addition to the canon of anti-imperialist filmmaking.

2. Dahomey (Mati Diop)

Mati Diop’s Dahomey, which won the Golden Bear at this year’s Berlinale, centers around the repatriation of 26 artifacts that were stolen from the Kingdom of Dahomey (now part of modern-day Benin) during the period of French colonial rule. Blending materialist history with an ethereal visual style, Diop creates an incisive, astonishingly elegant study of postcolonial attitudes, cultural myth-making, and the legacy of Western domination in Africa, as well as one of the year’s most poignant meditations on the idea of places as processes.

1. Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World (Radu Jude)

In his previous feature, Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn, Radu Jude attacked and ridiculed a decidedly Romanian brand of state bureaucracy. The result was astonishing, even if it did occasionally play into a kind of “provincialism,” as Jonathan Rosenbaum put it, in which global problems were presented as being exclusively Romanian. In his latest feature, Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World, the scope of his subject matter is much larger, and he rightly reserves his most lethal attacks not for the state, but for the far more dangerous (because largely unaccountable) concentrations of private power that inevitably come to dominate capitalist societies. And even when he does critique his native Romania, it is through comparisons and contrasts that constantly touch upon larger issues, such as the effects of American idealism in Europe, the inseparability of exploitation and wage labor, and the crucial role that the mass media play in systems of control and indoctrination. In my view, Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World is the supreme cinematic achievement not just of 2024 but of the decade so far.