In the press notes for Ben Stiller’s The Secret Life of Walter Mitty, the following is written underneath the film’s title: “Walter Mitty: n. An ordinary person given to adventurous daydreams far grander than real life.” Clearly, this isn’t your film studies professor’s idea of a notable New York Film Festival entry: Stiller’s film, his fifth feature as a director, is unabashedly nice, crowd-pleasing, and earnest, and the movie’s globe-spanning scale is perhaps too daunting a task for Stiller’s modest formal ambitions. But taken purely as a pleasant, holiday-season studio release, there’s really not much to take issue with here, especially because Stiller’s front-and-center presence — his choices as a director are always in permanent harmony with his character’s emotional state — effectively gives the film the feeling of a passion piece, making it easy to forgive and even disregard potential nitpicks.

The film’s plot, for instance, is surprisingly flimsy, resting as it does on what ultimately amounts to one man’s worldwide search for Sean Penn. Adapted from James Thurber’s classic 1939 short story (which was first turned into a movie, starring Danny Kaye, in 1947), Steve Conrad’s (The Weather Man, The Pursuit of Happyness) screenplay is consistently clunky in its balancing of real-world solitude and fantasy-realm illusions; that the movie’s fantasy sequences, moreover, are so broad and arbitrary (what in the world prompted that Curious Case of Benjamin Button gag?) depletes their resonance all the more. It’s hard to continue being invested in the movie’s central romance when, right after the two characters share a serious, adult conversation, daydream-prone Walter Mitty (Stiller) is suddenly imagining them living out the circumstances of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s age-distorting narrative.

What complicates this is that Stiller is clearly at home while depicting Walter’s corporate angst; he and cinematographer Stuart Dryburgh seem to relish the act of filming the strict, geometrical architecture of the Life magazine offices, the walls of which are all cloaked in steel blues and greys. When Adam Scott walks in, threatening beard in tow, as a managing director bent on transitioning Life into an all-digital enterprise, Stiller lingers lovingly on the roll of film his Walter receives from fabled freelance photographer Sean O’Connell (Penn). In a sense, then, Stiller has rendered Walter Mitty’s story contemporary by fashioning a rather blunt (though hardly unwelcome) allegory for the increasing evaporation of celluloid. The hazards of downsizing, meanwhile, position the film within a recession-plagued environment, with Scott and his menacing posse of corporate hounds looking to cut disposable employees.

Walter, with sixteen years of Life employment under his belt, begins to fear for his job when he can’t locate the O’Connell photograph that’s supposed to grace the cover of the magazine’s final print issue. Described as “the quintessence of life,” the photograph is mysteriously missing from the reel O’Connell mailed to Walter (though the two have never met in-person, Walter is the only Life worker O’Connell entrusts with his pictures). Walter’s mission, then, becomes a sort of adventure-mystery, with him using the roll’s workable photographs — one is a close-up of a thumb, another hints at the name of a boat — to attempt to locate the famously remote O’Connell. Walter’s journey takes him to Greenland and eventually Iceland; comprising the film’s middle section, these sequences are basically just an extended travelogue, complete with small, odd, offhand scenes (like one altercation with a drunk Greenland pilot, played by Ólafur Darri Ólafsson) and conventionally life-affirming montages set to Arcade Fire and David Bowie.

Much of the information accumulated during this section of the film comes off as extraneous and not necessarily crucial to the story. Because Stiller nails his character’s situation so nicely in the film’s opening scene — in which Walter goes to great lengths to try to “send a wink” to the eHarmony profile of a co-worker (Kristen Wiig) with whom he’s smitten — most of the additional background information we get of Walter (former employment at Papa John’s and KFC, a longtime affinity for skateboarding) only serves to make the character’s persona more confusing. Stiller’s Walter is so efficiently conceived on a visual level — the short-sleeve dress shirts, the monotone windbreaker, the loupe glasses — that we come to understand him quite immediately on an intuitive level; the abundance of eccentric character traits isn’t needed.

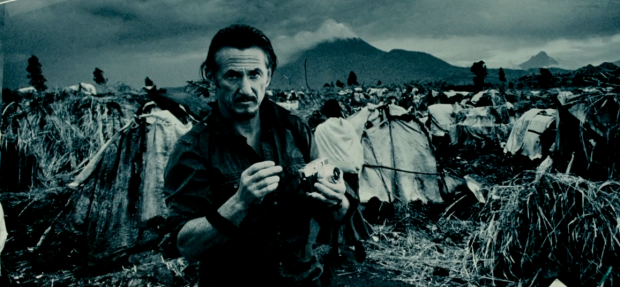

In addition to Wiig, who’s very sweet in a pretty basic role, Stiller is surrounded by the likes of Kathryn Hahn, as Walter’s quirky, performance-artist sister; Shirley MacLaine, as Walter’s mother; and, unexpectedly, Patton Oswalt, as an eHarmony consultant from whom Walter seeks help. That these minor characters are mostly forgettable is another sign of the strength of Stiller’s character; as written, they all seem thin and even boring when compared to Walter, which is saying something, since he’s the one who’s supposed to be going through a mid-life funk. That the film chooses O’Connell’s AWOL photograph as its consummate gesture further reflects its harmlessness: it’s entirely possible that your opinion of The Secret Life of Walter Mitty will hinge on whether or not you like the picture that appears on the final print issue of Life magazine. I like the photograph, and find Stiller’s sentiment there to be kind and genuine; therefore, I think The Secret Life of Walter Mitty is a nice movie.

The Secret Life of Walter Mitty screens this weekend at the New York Film Festival, and will open in theaters on December 25th.