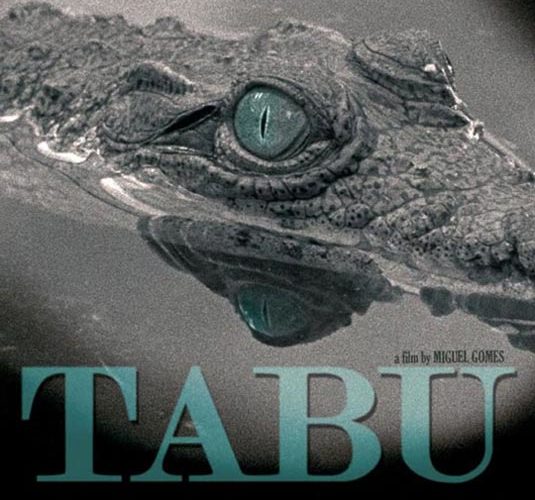

Miguel Gomes‘s Tabu, one of the year’s true incarnations of movie magic, is an irresistible tailspin into a world that covers everything from an old woman’s gambling addiction to suspected witchcraft to symbolic crocodiles. There is, to be sure, a longingly romantic narrative that unifies all of these things, but the film’s more resonant connective tissue is its heartbreakingly nostalgic, wistfully yearning spirit, which Gomes, working with his usual cinematographer Rui Poças, communicates through pristine black-and-white photography.

Structurally — and likely in a few other ways, as evidence by, well, the title — Gomes‘s film is inspired by F.W. Murnau‘s 1931 Tabu: A Story of the South Seas, which was split into two separate halves: “Paradise” and “Paradise Lost.” But whereas Murnau‘s Tabu proceeded according to that order, Gomes‘s Tabu inverts the paradigm by opening up with “Paradise Lost,” a dizzily, at times even frustratingly dry story about a withdrawn woman named Pilar (Teresa Madruga), who, though retired, is nevertheless kept very busy by her eccentric, debt-ridden neighbor, Aurora (Laura Soveral), and the black maid (Isabel Cardoso) believed, by Aurora, to be partaking in voodoo-related activity.

The general aura at work here is mystery, because the characters do things that suggest a lifetime of despair and conflict — conflict that we desperately want to learn more about. This is predominantly true of Aurora, because, while Pilar isn’t an uninteresting personality — in one scene, we see her crying in the middle of a movie theater, her companion asleep beside her — she at least appears graspable. One of her behavioral ticks is to hang up a painting whenever the work’s artist is dropping by, and then take it down once the artist leaves, and we sense, in this considerate gesture, the prevailing aspects of Pilar’s character.

Aurora is different — more mystical and enigmatic, and not solely, we suspect, because of her various old-age afflictions. It’s something much deeper, as Gomes and Soveral get across in her introductory monologue, which takes place in her regular-jaunt casino. Employing minimal cuts, a dreamy close-up, and giving his actress an intimidating pair of dark sunglasses, Gomes is able to create an immediate fascination about Aurora — nobody without a whammy of a past could give a speech like this right off the bat.

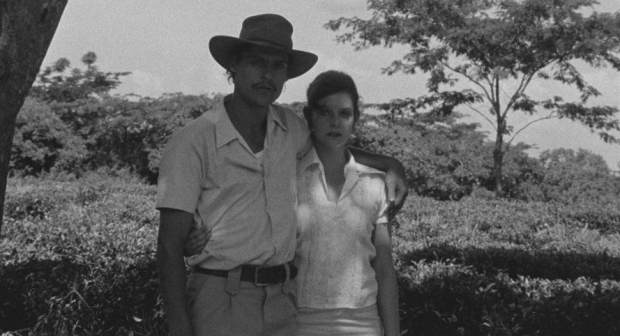

And then, a little later, comes “Paradise,” an extended flashback narrated by Ventura (Henrique Espírito Santo), who we learn was a deeply significant figure during Aurora’s early adulthood. (Santo, who plays Ventura in his old age, provides the voice-over; Carloto Cotta plays the character in the younger years. Ana Moreira, meanwhile, plays the youthful Aurora in the film’s second half.) Set in Africa during the onset of the Portugese Colonial War, “Paradise” remains intensely personal in its focus on the illicit, impassioned affair that develops between Ventura and Aurora.

It’s in “Paradise,” too, where the Murnau influence is felt even more. Essentially throwing out dialogue altogether — there is, remember, that poetic, stately narration — the film’s second half takes on the overall pacing and feel of an enchanting silent film, and though this may be a trite thing to say, it’s one that, in all honesty, makes the Best Picture-winning The Artist look like child’s play. There’s hardly a single detectable word spoken between Ventura and Aurora throughout our witnessing of their budding affection, but what Gomes records instead — the nature-sounds that surround them, including chirping birds and crunching leaves — gradually works its way under our skin.

The reason for this is not simple romanticism — as uncommonly rapturous as the film may be, it’s still seeped in the sadness of “Paradise Lost,” so the dynamic between the two young lovers at times plays like a melancholic photo album, filled with snapshots of people who went on to live much sadder lives. You could make the argument that the film’s recurring Portugese cover of “Be My Baby” ensures some measure of emotional hope, but the unforgettable rendition of the song ultimately does more to seal the deal on the unfortunate futures that await these two people, who want nothing more than to live in each other’s perspiring arms under the shadows of Africa’s Mount Tabu.

The genius of Gomes‘s formal devices here, however, is more related to their rather amazing commitment to the intention of realizing Ventura’s memory. Think of all the films you’ve seen that use this narration-driven flashback structure to tell a decades-old story, only to then give us a handful of extended dialogue scenes that delineate a relationship’s development. Can people actually remember entire conversations once they’re four or five decades removed from them? I don’t think so, and neither does Gomes. What they do remember is the smell of the place they were at, or the sweaty lips of the person they were with. I’m proof of this myself — two weeks removed from having seen the film, I’m not sure I can recall one word of Ventura’s voice-over, and yet the blissfully beautiful sensation of Tabu continues to linger like a bedside photograph.

Adopt Films will release Tabu on December 26.