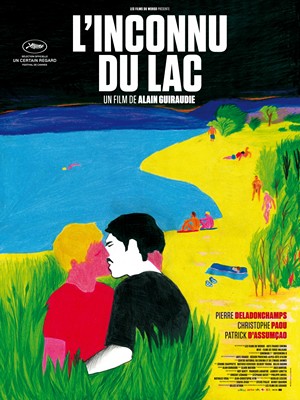

The parking lot, always glimpsed from the same perched, high-angle camera position, is the edge of society in Alain Guiraudie’s Stranger by the Lake. Men pull up here, in their cars, take a short walk through the forest, and emerge onto the shore of a lake, where the sun reflects off the water, leaving little sparks of summer light. The men sunbathe, gossip, chit-chat, ogle — and, above all, cruise. Guiraudie’s film never leaves this location; his coiled, merciless plot is constructed entirely out of what these men do near this lake over the course of a handful of bright days and portentous evenings. At first glance, there doesn’t seem to be much reason for conflict: many of the men know each other and are friendly, and the ones who don’t are generally content to hook up in the trees and then part ways. But the film ends in blood and ambiguity, revealing a dim view of human nature.

The other Guiraudie film I’ve seen, 2001’s hour-long Sunshine for the Poor, also took place in a single, isolated setting: the dry fields and wide vistas of the Causses. But Sunshine for the Poor had a kind of magical-realist quality that is largely absent from Stranger by the Lake, which has a psychological and atmospheric intensity that doesn’t often make room for light comedy. (Which isn’t to say the film is never funny, but rather that the laughs are almost all underlined by urgent suspense.) The film’s main character is Franck (Pierre Deladonchamps), a twenty-something hunk who arrives at the lake looking to kill some time in-between jobs, and ends up experiencing a whole lot more.

The first relationship Franck strikes up isn’t of a sexual variety, but a gentle, conversational bond with a heavyset older man named Henri (Patrick D’Assumçao). Henri, who has been with women before and seems to consider himself no longer sexually active, sits far away from most of the other lake dwellers. Understandably, many of Franck’s friends are confused by Henri. Why does he show up every day if all he does is just sit and stare out at the water? Guiraudie’s handling of the Henri character is one of the film’s great pleasures: at a certain point, he and Franck begin inviting each other out for drinks or dinner, and, because Guiraudie refuses to leave this setting, we’re invited to imagine their encounters based on what we, the viewer, have observed of them at the lake.

To be sure, speculation regarding these men’s overall lifestyles isn’t limited to Henri and Franck. Indeed, the amount of time these people spend at the lake raises all sorts of questions. Do they have jobs, families, other friends, or even other cruising spots? Guiraudie’s compact, deliberately snug narrative seems to have a game with the audience: because there are large sections of the film during which nothing of note happens (outside sex), we have no choice but to feast on small details and see where they might take us. Simple colors or items of clothing — a pink polo, running sneakers, a Batman T-shirt, a left-behind condom — become the focal points of scenes or moments, drawing our attention and tempting us to consider, even momentarily, the significance of these seemingly stray objects.

The movie takes a turn when Franck locates an object of fatal attraction: Michel (Christophe Paou), who almost looks as if he could’ve been Tom Selleck in another life. Michel reciprocates Franck’s feelings, and the two have sex like nobody’s business. Guiraudie, pushing the envelope in interesting, provocative, likely NC-17-caliber ways, populates his film with unsimulated sex, on-screen ejaculation, and climaxing staged in haunting silhouettes. This already-heated relationship takes on an added dimension when, one evening, Franck witnesses Michel drown one of his hook-up buddies. Guiraudie films this scene in an astonishing point-of-view shot, which is held so long we almost forget that Franck is even part of the scene. Franck’s knowledge of this event — and his dual unwillingness to report it and end his relationship with Michel — forms Lake‘s central tension.

This is clearly an enjoyable thriller scenario, and Guiraudie crafts the film with spotless composure — stringing out Franck’s moral predicament for everything it’s worth — but the idea of sex and death as related, intertwined companions isn’t at all revelatory, and when it becomes clear that Stranger by the Lake isn’t totally gunning for anything more ambitious, the movie hits a bit of a standstill. When that realization arrives, our expectations of the film shift slightly, and all we’re looking for is a good, punctual, visceral knock to the teeth — something which Guiraudie’s splendidly gruesome conclusion, with its off-screen footsteps and increasing body count, delivers with authority. But when the abrupt cut-to-black arrives, there exists the feeling that a more profound film is probably hiding somewhere amidst the careful gestures.

Stranger by the Lake will screen at the New York Film Festival on September 30 and October 2; Strand Releasing is currently planning to open the film, theatrically, in spring 2014. One can see the trailer above.