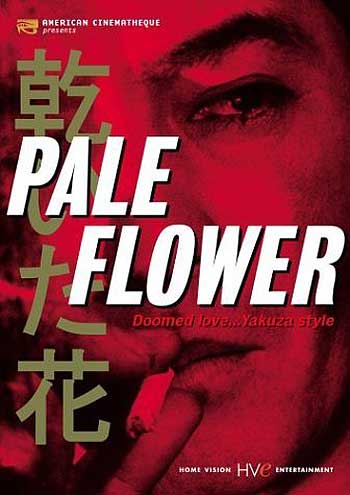

For over 40 years Japanese director Masahiro Shinoda both played within the confines of genre and sought to break from those same restrictions in exploring universal themes, such as faith and mortality. Shinoda’s 1964’s Pale Flower and 1971’s Silence, two of the Shinoda prints selected to play during the New York Film Festival, reflect this diversity on a rather epic scale. On one hand there’s Pale Flower, a black-and-white, well-paced, simply-told crime saga concerning a career criminal and the woman who wins his cold, cold heart. On the other is a sweeping tale of Catholicism and martyrdom, featuring landscapes and vibrant color – for at least some of the time.

Flower, while more successful as a narrative and more impressive on a technical level, lacks the personal passion present in Silence, which seems to be a reflection of Shinoda’s own conflicting beliefs. That said, both films feature principled protagonists who break their own rules. Muraki (Ryô Ikebe), in Pale Flower, is James Cagney in Angels With Dirty Faces or Rick from Casablanca or the master thief in Jules Dassin’s Rififi: a man built on guilt and regret, determined to look out for himself. But, of course, he remembers how to care and how to love, thanks to a broken beauty.

This is cliched stuff, even back in 1964. Thankfully, Ikebe’s turn as the criminal is both enigmatic and familiar, like recognizing yourself in the mirror after forgetting what you look like. Likewise, Mariko Kaga’s performance as Saeko, the aforementioned beauty, is haunting. She barely exists in Shinoda’s film, more like a wild spirit or painful memory. She’s lit like Barbara Stanwyck in Double Indemnity but plays the role of the “pale flower” like Ingrid Bergman at her most vulnerable.

Scenes in a back-alley gambling den linger for far too long. And then Saeko enters, and the viewers, much like the other gamblers in the frame, are brought back to life. Who is this woman? And why is she here, of all places?

Shinoda’s Muraki is a samurai in many ways, silent, stoic and loyal to his calling. He does what is asked of him by those he worked for before he went to jail, and now works for again. From what we can tell, he’s stronger, in every way, than these men, but follows them anyway. Thanks to this stubborn loyalty, the conclusion of Pale Flower will be far more frustrating and significantly less romantic for American audiences than that of Casablanca or The Asphalt Jungle. But the passion’s there, deep in the narration, in Muraki’s face and in Shinoda’s frame. SPOILER ALERT: Standing outside in the bright, overexposed prison yard, Muraki receives news that Saeko has been murdered. Upon hearing this, he’s told his time outside is up and retreats back inside. In seconds the light evaporates, a sliver following Muraki inside the abyss as the door outside closes.

Nearly every frame in the first 30 minutes of Shinoda’s Silence is as arresting as this final shot in Pale Flower. The setting is 16th century Japan and the camera reflects as much, offering grand exteriors full of nature, the main players in the film dots within a tapestry of greens and yellows and blues. The protagonist, a Catholic missionary, is on a search for his mentor, lost 5 years ago and feared captured by the anti-Catholic Japanese government. His journey appears futile at first, as he and his fellow missionary find themselves in the middle of a firefight, trapped in a cave. When they ask of their mentor, they’re met with laughter. This is a simple, yet intriguing, metaphor for the Catholicism these two missionaries intend to bring to a Japan bred of tradition far from Christ and crucifixes.

Throughout, however, Shinoda’s hero remains steadfast, determined to complete his mission/s. He instills Muraki’s loyal determination, if not for a greater cause. Of course, this cause becomes the focal point of the film’s second half and, somewhat ironically, its downfall. Vivid locales and ambitious camera moves are replaced with stale prisons and meeting corridors populated with tired dialogue concerning the necessity of Catholicism in Japan. Our hero feels Catholicism, and its significant number (though they be a small minority) of Japanese followers, deserve the right the practice it. The government goon who’s imprisoned our hero does not. It amounts to two censored history books yelling at each other, and with about as much charisma.

And though it’s ending be troublesome and daring, it is also overwrought and unbelievable. Shinoda has built a martyr in our hero, only to break him down. Unfortunately, our hero plays it too strong to not choose martyrdom when the time comes. And if Shinoda’s point be that no one is too strong, perhaps it is well made. History, unfortunately, does not support the claim.

Shinoda’s filmography will be played through the NYFF at the Lincoln Film Center.

Do you know Shinoda? What do you think of his work? These works in particular?