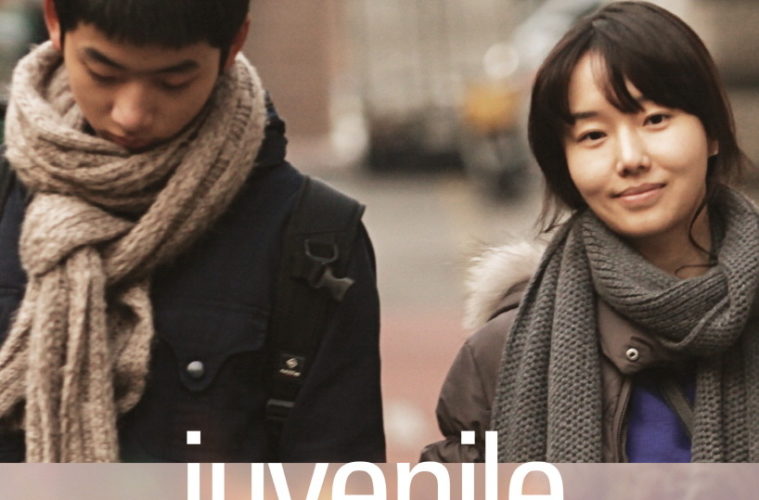

Yi-Kwan Kang’s Juvenile Offender is a film 2Pac would have endorsed, as its struggle feels completely universal: misguided youths are bound to repeat when another way of life is unknown. Fittingly, I saw this film the same day I saw the film adaptation of Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children (a complex film also dealing with socialization as two children are switched at birth). Kang’s film, produced by the National Human Rights Commission of Korea, is an intimate work of social realism.

16-year old Ji Gu (Seo Young Joo) has been abandoned by his party girl mom Hyo Seung (Lee Jung Hyun) and has been raised by his terminally ill grandfather. In and out of detention centers, and on probation, Ji Gu is in a relationship with a young women (whom we see as the film opens) and life of crime. I’m not sure if the punishments are too lenient or there isn’t the proper social program to curb this behavior but Ji Gu is given time to “think” about the path his taken, perhaps ever receiving the proper mentorship.

Juvenile Offender is an intimate film and it does not glamorize teen violence or bring it to the extremes of Larry Clark’s work; it’s more on par with the Dardenne Brothers or Mike Leigh, a study of social structures and really terrible decisions. Once out of a brief stint in a detention center, Ji Gu is reunited with mom, a hairdresser with serious financial problems. They flounder, attempting to reconnect they never quite as they move from cheap apartments and hotels, never finding stability.

Observation and restrained, Juvenile Offender is mature and subtle, although quite frustrating. The film bares similarities to a National Film Board of Canada classic, Nobody Waved Good-bye, about a troubled youth from an otherwise upstanding family (that film I imagine must have been produced as a cautionary tale for high scholars). The National Human Rights Commission of Korea perhaps funded this film as a brave means of self-exploration, questioning if a system been created to fail juvenile offenders. While the film is a grounded character study, it aims to expose the larger system and in a very modern society, it appears there is no safety net. These kids are detained verses rehabilitated; it’s no wonder every time he’s caught, Ji Gu asks “can you forgive me, just this time?”

Bleak, the film never lets up nor does it sensationalize any part of this experience; Ji Gu’s motivations for his behavior are also never truly clear either. What is clear, from one painful scene in particular with his mother, is he has been left to fend for himself with no good role model. The film is less a cautionary tale than it is a matter of fact; detention isn’t like Oz — in fact, like much of Ji Gu’s life, it’s a circumstance.

Juvenile Offender screens tonight and on July 11th at the New York Asian Film Festival.