Northwest India’s Jammu and Kashmir region resides at the center of a longstanding geopolitical stalemate involving neighboring Pakistan. While those tensions are referenced in The Shepherdess and the Seven Songs, they are not the film’s focal point. Instead, paranoia and opportunism have become fully ingrained in the forest area’s mountainous bedrock. Of more importance is why these characters either accept or subvert such societal realities, and how they normalize modes of corruption and gender inequality under the guise of tradition or progress.

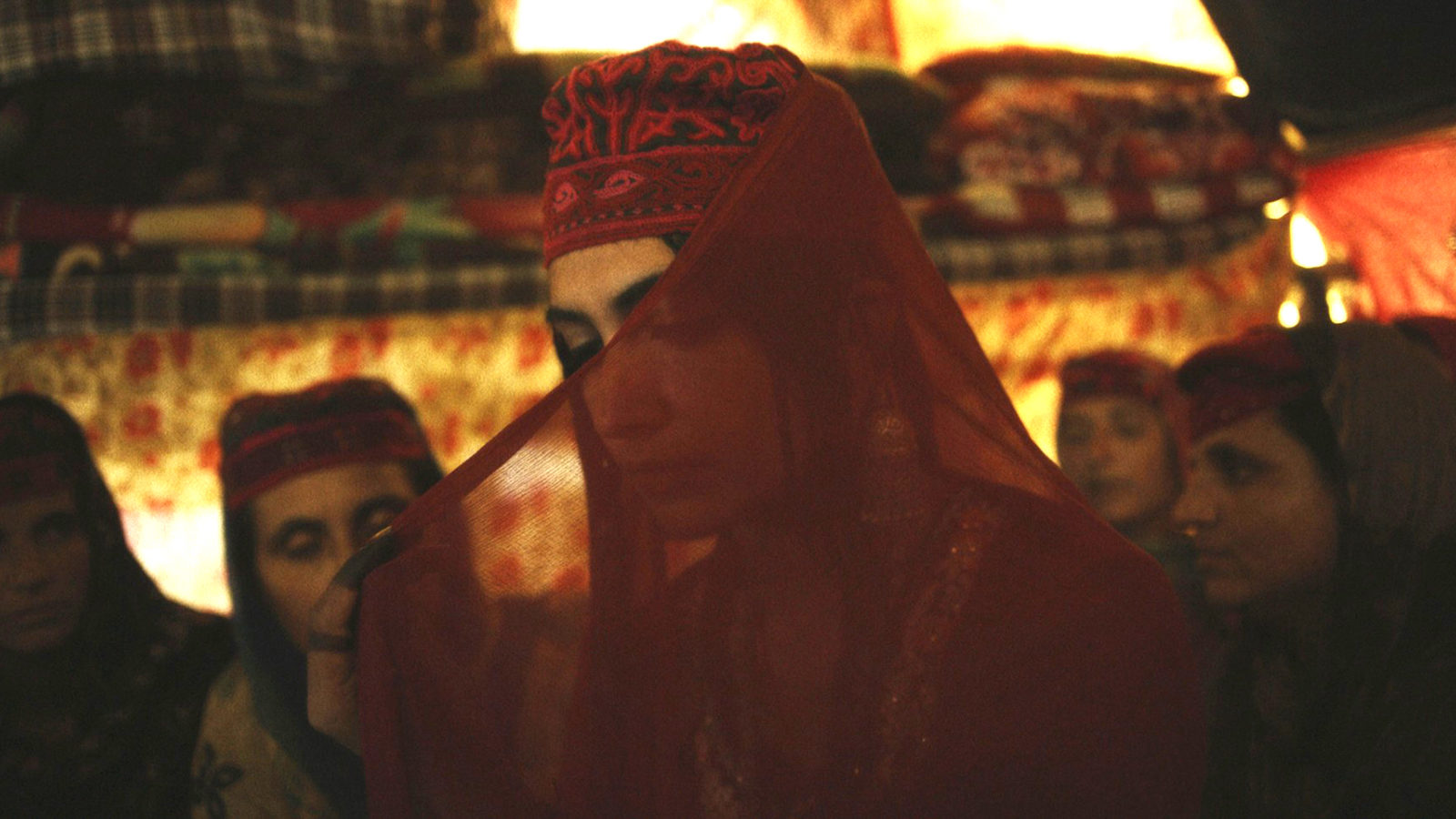

When split in half, the title of Pushpendra Singh’s riveting character study represents competing forces of assimilation and freedom, patriarchy and artistic expression. Laila (Navjot Randhawa), who comes by her occupation not out of choice but an arranged marriage to the shepherd Tanvir (Sadakkit Bijran), embodies this strain wholeheartedly. To make sense of the suffocation felt as an independent woman in spirit and kept bride in practice, she relies on the titular melodies as guides, both acknowledging and upending the very traditions that have landed her in a cultural briar patch of which there is no escape.

Tanvir’s nomadic life takes them (and their massive flock of goats and sheep) across invisible borders and literal slopes. Eventually, he and his family’s extended clan arrive at a small frontier hub. Almost immediately, the sleazy forest guard Mushtaq (Shahnawaz Bhat) takes an interest in Laila, as does one of his superiors in the local police force. The lecherous men make half-assed attempts at seduction, having wielded this power many times before. Laila grows increasingly angry at their brazen callousness, and even resorts to violence in one instance, emasculating and enraging them both. But these horny flies won’t be easily shooed.

Singh’s methodically well-paced film slowly escalates a potential for betrayal and disaster, mirroring the tightrope stakes of great neo-noirs. Laila flirts with the role of femme fatale, attempting more than once to set up situations where surprise confrontations between men would spiral into brutal retribution. At one point, she confesses through voice-over, “Why am I playing this dangerous game?” But the answer to that question is clear, and it has to do with reclaiming the power of identity and self.

Laila’s reawakening is also sexual in nature. Consistently turning the tables on Mushtaq helps clarify physical desires that now seem emotionally connected to an otherworldly call clarified further by the songs themselves. Fittingly, Singh’s film remains malleable to the very end, defying any indication of B-movie tropes for a narrative direction more suited to Laila’s choosing. A telling conversation with Tanvir reveals the film’s true intent. “One has to be polite to powerful people,” he says with the utmost clueless male privilege. Laila defiantly responds, “For how long?”

Even genre, it would seem, is just another storytelling form that Laila wants to break free of no matter the cost. The Shepherdess and the Seven Songs admits as much in the hallucinatory finale, stripping away all distractions and boundaries associated with linear narrative. For so long her ferocity as a woman (Mushtaq often calls her a “tigress”) has been defined entirely in masculine terms. But when that aged, archaic filter is finally removed, Laila is not remade or renewed, but given the chance to remake and renew on her own terms, away from the male gaze completely.

The Shepherdess and the Seven Songs is now playing at New Directors/New Films 2020.