“Focus the text” commands a translation app pop-up at the mid-point of Matías Piñeiro’s new experimental essay film You Burn Me. It’s a mantra that the Argentinian filmmaker has taken to heart. Using Sea Foam, a chapter from Cesare Pavese’s book Dialogues with Leucò, as a creative catalyst, Piñeiro envisions audiovisual dialogues between characters (Sappho and Britomartis), between actresses (María Villar and Gabriela Saidón), between filmmaker and text. As pertinent pages and mnemonic games unfold, repeat, and recontextualize, the spectatorial thrill of Godard’s Goodbye to Language comes to mind. This a formally bold, playful, reinvigorating work––a love letter to language both verbal and visual.

After a warmly received North American premiere at last year’s New York Film Festival, You Burn Me opens in the U.S. in limited theatrical release this week from Cinema Guild. I first saw the film last June, when it had a U.K. premiere at London’s Institute of Contemporary Art. Returning to You Burn Me now, I notice details that previously escaped me, and I find myself bringing different focuses, reflections, and points of interest to my spectatorship. Watching You Burn Me is a highly active, participatory viewing experience that profoundly reflects the film’s central concerns, its text, its process, and its form. Sitting down with Piñeiro over Zoom, we expand that text further.

The Film Stage: I want to start by exploring how You Burn Me differs from your past work. You had made many films exploring Shakespeare. Recently, your Sycorax co-director Lois Patiño went on to make Ariel, and you went off in a different direction. What prompted you to depart from Shakespeare towards these new horizons?

Matías Piñeiro: I was initially involved in Ariel, and I was thinking that it would perhaps be my last Shakespeare film. Due to circumstances of scheduling and life and so on, I had to step out from the project. All of a sudden the Shakespeare cycle––a project of ten-to-twelve years––had ended. It was not that I declared “now I finish the cycle.” I had to step out, and then the cycle was over. It was an interesting thing for me.

In the meantime, this other text appeared––the Cesare Pavese text. At first I sort of resisted it because I wasn’t able to fully finish the book; it’s very dense. But then, on a second try, I found this text, the one between Sappho and Britomart: Sea Foam.

There’s something in there that I hope is exposed in the film, this thing of Pavese––a man of literature who kills himself––projecting himself onto the figure of Sappho. He not only wrote the Sappho lines, which have to do with these ideas of death and desire, but also the lines of Britomart, the [figure that] is accepting life, accepting conflict––coping. For me it was interesting that, in that text, you would have both energies, not just one. That’s why it was important in the film not to fall upon the admiration that you can have for a figure such as Pavese, to instead try to go beyond the romantic myth of the troubled artist.

I do think that the Shakespeare cycle needed to end, in a way. I usually make films because I react to literary texts, such that I somehow feel that they should be put up there. Usually those texts offer a resistance. I wouldn’t say that it was obvious that I would make films about Shakespeare’s comedies. But it was interesting to spotlight those works more than they had been, putting the focus on the comedies that were supposed to be minor, working around that. With Pavese, the text is so dense that it offered me a challenge of what to do with it. Where is the enjoyment of this text? Where is the enjoyment in this resistance? What is it that can be shared?

Why an essay film, rather than something more theatrical?

In 2020, I practiced this more essayistic form with Mariano Llinás, a filmmaker friend from Argentina. We were asked to conduct a video correspondence during the pandemic. Something in that experience opened a gate, which I continued through in You Burn Me.

I’m not only adapting the text, but also the idea of footnotes. The book is full of footnotes, and those footnotes make the text bloom––they expand the text. I said, “Why not include this information if it’s what is making me have a stronger connection with the text? So what could a footnote be in cinematic terms?” It made me go there very intensely, working with these ideas month after month. It’s not that you fully consciously decide. You suddenly get interested in something, and that something has a question that you aren’t able to resolve. So you insist. And that’s how you work.

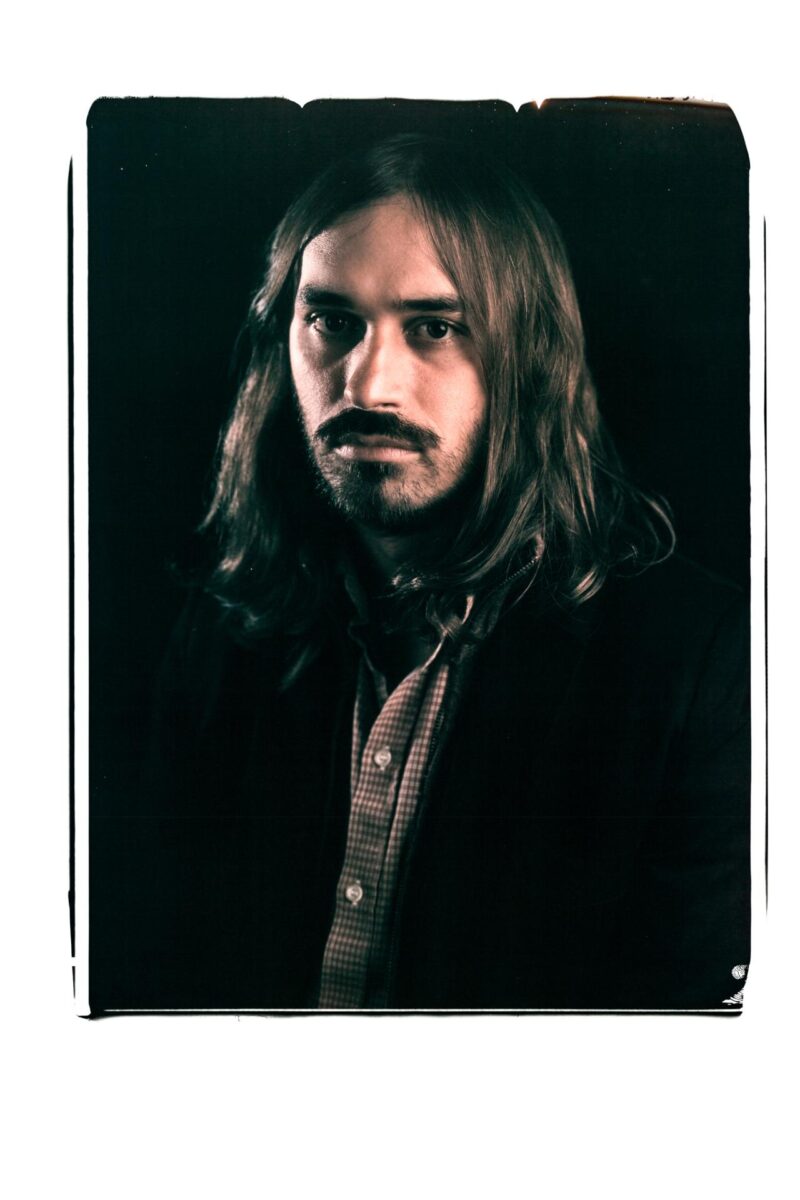

Matías Piñeiro

What do you feel this process of deconstructing and reconstructing a text can do for us as artists, as audiences, as human beings?

Maybe understanding that knowledge is pleasure, in a sort of Rossellinian way. Cinema, for me, is a medium to share materials and to multiply them––to invert them, to give variations. We go back to texts and see them differently. I realized, in the beginning, that I hadn’t read the Shakespeare plays. I read them in high school and that’s it. One or two, and I hope that there were no abbreviations of the text. Even with a name like Shakespeare that is so big, you take it for granted and then you lose the detail. So what I like to know is: have you read this little one? Have you read King John, for instance? I know there’s something interesting in this paragraph here, you know.

I like the idea of detail. I hope that we can pay attention to small details, small segments. We provide a lot of stimuli, and I hope that people will connect through different parts of that stimuli. It’s about sharing––enjoying information and seeing things for the first time. Sometimes what happens after screenings is that people want to go out and read the text. It’s a nice thing for me that it expands from the cinema also.

What led you to “You Burn Me” (“Tú me abrasas”) as the key, titular phrase of this film?

Initially, I didn’t intend to title the film that. I knew that I wanted it to be a poem by Sappho. If I had to think fast, maybe the film could have been called Sea Foam––the name of the text that it adapts in full. It was the first time that I was adapting material in full. With Shakespeare, I was just riffing here and there. But then I thought that the title was too much Pavese––what the movie needed to do was to confront Pavese. By making the title a poem by Sappho, I would be shifting the balance.

The movie has this idea of memorizing, of learning by heart. There are a couple of sequences where we play around with this idea of the memory game, to learn Sappho’s poems by heart. The movie also does other things with the text: little adaptations and jokes, or they become dialogues. I thought that making You Burn Me the title would be another way of memorizing it.

I wanted to do three of these memory games. One with a three-word poem, which ended up being You Burn Me. Then one with eight words. And then I wanted one with a lot, like 30. It would be very kaleidoscopic, but I thought that it was a little excessive, so I changed it. But the other two remained.

You have a finished film that almost functions like a thesis––you’re presenting the findings of your research. I’m curious as to whether you feel that your film has a finality to it, or if you feel it’s open-ended, that it expands beyond the film that we see?

I think it’s open-ended. And that’s not just theory; it’s practice. Two weeks ago I premiered a short film that is a preface to You Burn Me. I finished the movie in February of 2024. At first I was going to make a trailer, but then it went off-track and became much more than a trailer; it became an independent thing. Pavese’s book has a lot of prefaces; they’re a key element in the text. And I said, “This is a preface, actually.” It’s an idea that I couldn’t include––the movie actually rejected it––so we had to leave it out. I felt that it would also give context to how the film is before it starts. Maybe audiences are familiar with my Shakespeare films. So now there’s a preface: six new minutes that give a sense of what the movie will be.

When I was shooting I really wanted to keep myself in that state. I didn’t know how the movie was going to be. I started with the idea of the memory game. I knew that I wanted to do something with Pavese’s text. I didn’t know how to shoot it. I filmed around San Sebastián and New York and put shots together to see if this memory game worked. It did, and I continued it. From October 2021 ’til January 2024, I shot almost every month. It’s not that there was a thesis. I was working on a form. I was working on patterns, working and reworking. I was finding the movie while I was making it. I wasn’t pressured to end it, but there’s a moment where you feel that you found a balance. It’s a hybrid between fiction and essay, but it’s not that I had a “point” to make––more that I wanted to move around certain ideas.

I didn’t want to make Pavese a totem. He’s a wonderful writer; I wish that he wouldn’t have killed himself. But I didn’t want to romanticize his suicide as so many movies do. Myths and the construction of myths are very male-centric, and there’s a lot of mythology in the text. So it was how to work with that and somehow point out how those myths are representing a certain society. All the time, there was the problem of how to bring that text into images and sounds––how to open it up, how to put it in circulation. What is the movement of this text? What are the images that would allow this text to move around? That was my research.

Do you think with the same logic when manipulating images and text? Do they come simultaneously to you, or do you find that mentally editing and manipulating fragments of text versus image takes a different kind of mental acuity?

It required a different way of working for me compared to my previous films. Did I take the scroll to London? I have it here.

[Piñeiro produces a paper scroll, 25 meters long, to which shots from the film have been affixed along a drawn chronological timeline.]

You showed photos of it during the masterclass at the ICA.

Yeah. With this object I was able to find the position of the relationship between images and sound. I wrote the whole text, and then I started associating it with the images that I had. Then I started creating the detours of what the footnotes could be and what images could be related. And then what I was missing, I still had to shoot.

In this process of shooting, writing, shooting, editing, writing, etc., you’re constantly combining. That was something that I also did a little bit in Isabella, my previous film. I printed the shots of the movie, like this, and I would say: “Okay, which one comes first? Okay, this one has to come first.” But then I’d grab another one and say: “Should this go after or before this new compound?” And so on. It was by combining and seeing the results that I found the form. And I needed it as objects. I needed to touch physically, I needed to cut, to print, to manipulate, to carry it in my backpack.

I needed to take time, also. This slowed me down. Same thing with the 16mm. Digital is too fast and it wouldn’t have allowed me to find detours. You fail and you reconstruct. That’s why I’m always shooting: there are wrong paths. You need to rewrite; you need to reshoot. I shot around six hours in 16mm, and the movie is 1 hour and 10 minutes now. There’s a lot that I left out because it didn’t fully work.

You mentioned gender, and it’s an interesting aspect of this film. In your previous films, you centered women prominently onscreen. Here they’re focused through voiceover and the characters in the text. What has that shift done for you and the film?

I think that has to do with Pavese’s text. It’s the only chapter where it’s two women talking in the whole book of Dialogues with Leucò, which I think says something. Pavese seemed to have a problematic relationship with women, and it showed in his work. It’s not so innocent that myth was a way to convey certain ideas of his. So there was a need to review that, and to expand––because Pavese is a complex figure. We should not reduce him. We should expand.

The collaboration that I have with María Villar and Gabi Saidón, the actresses and musicians of the film, is very strong. A movie is an opportunity to meet and to create encounters––to create a life together. In my previous films there was a crew with ten-to-thirteen people. This one was mostly shot between three people. It’s very different––up-close, intimate. That intimacy has to do with friendship. The film was a good excuse to meet and to see what the meetings would provoke. The meeting is not only with humans, but also with books or with a city. It’s the intersection of all these elements. As a man I also needed to have this energy, this relationship with different women. It was important to listen because I was going to have a lot of biases. There were discussions around how the poster should be, for example, with the producer Melanie Schapiro. They helped me to understand how it’s better to think certain things. It’s like a cinema family, in that sense. I’m not the employer, and it’s not an industrial bond.

This is a highly formally inventive film. What excites you formally in cinema beyond your own work at the moment?

One that’s a big reference for me is Hong Sangsoo because he’s constantly breaking patterns. People think that he’s always doing the same movie, but he’s constantly changing. Of course, not in a psychotic way. It’s not that now he’ll do the complete opposite. There’s a sort of working program, thinking and rethinking. It’s interesting to see how he stops doing the zooms. He’s doing things that he hasn’t done before. That extreme close-up of Isabelle Huppert in A Traveler’s Needs. Then in By the Stream, he comes back more to plot again, like in the films that he did in the 2000s. He’s constantly trying to escape, a bit like the Cheshire Cat. And there’s something about how he merges production with the formal ideas of his films. I’m very interested in how he’s becoming so small. At the same time, the films become so blurry––not only because the image is sometimes blurry, but because the relationship within the shots is very ambiguous. He keeps on pushing certain boundaries in this world of fiction.

Mariano Llinás made this huge movie, La flor, and then now he’s making these more essayistic, smaller films––one every year, when he used to do one every ten years. I’m really interested in that sort of transformation.

And I’m interested in films by new filmmakers, such as Paula Tomás Marques, a friend of mine who just premiered her first film in Berlinale. I like films by Nicolás Pérez, for instance. Roberto Minervini. Eloisa Solaas––also from Argentina––she did a documentary called Las facultades that is very good. There’s a constellation of films everywhere. I’m, of course, forgetting a lot of great films, but I must say that Hong is making us used to having this meeting with him once or twice a year––which I’m always very excited by, because I think that he’s always running away from what you expect him to be. There’s something very provocative in that.

As a final question: where are you heading next with your cinema? The libraries of the world are vast.

I’m already working on something. I’m working with a Francesco Petrarca text called Remedies for Fortune Fair and Foul. It’s cool. I started shooting last August, and I’m shooting more later this year.

It’s always literature. I don’t know why. Or theatre. I think that the thing that I’m seeing as a continuity is that the Petrarca is also a text made up of dialogues––similar to the Pavese. It has this more essayistic side. I’m always going to be making things that are a little bit hybrid, but with this one I want to experiment with form whilst also embracing fiction. I think that fiction can be a way of experimenting. I don’t think I’m going to be shooting text in a book in this one. It’s a fiction film that will have very explorative and curious ways of being.

You Burn Me opens on Friday, March 7 at New York’s Anthology Film Archives, accompanied by a special series curated by Piñeiro, and will have its Los Angeles premiere on March 15 at American Cinematheque as part of a series featuring films by the director.