At this year’s Tribeca Film Festival, Robert De Niro hosted friend and collaborator Martin Scorsese for a freewheeling conversation about the director’s career. They discussed his titles ranging from their 1982 flop The King of Comedy (and how it was resuscitated by film culture) to Scorsese’s massive success with Leonardo DiCaprio in 2013’s The Wolf of Wall Street.

Seated at the Beacon Theatre, the duo tie their latest project, The Irishman, into Scorsese’s oeuvre of operatic scoundrels. De Niro introduced the book I Heard You Paint Houses to Scorsese, which the director chose as the feature film to follow his 2016 religious epic Silence. “You profoundly feel the heart of this character and the situation. It’s a universal story that happens to be set in that world,” Scorsese said of Frank “The Irishman” Sheeran’s story, played by De Niro. Scorsese’s other Irishman tidbit is the movie borrows musical themes from other films, à la Casino.

We’ve excerpted the best of their conversation. Each section features the clip Scorsese used to talk about his films and his breakdown of how the scene came to be.

Mean Streets

This scene gave an evolution to the film when I was cutting it. I know you did Bang the Drum Slowly and Brian De Palma’s films, but when Mean Streets was released, this scene is the one I think grounded our careers. Something just shot out of the screen. It was your idea to do it because you felt Charlie, played by Harvey Keitel, goes through so much to defend your character Johnny; it’s complicated, but he does. You said I had to show how Charlie was taken in by Johnny. You came up with an improv and I wrote down those notes in a little book. On the last day of shooting I had to beg our producer, Jon Taplin, to give us another two hours to shoot this, and I forgot the book! You had to remember everything from four weeks earlier.

When I made this movie it was a real dream, but I didn’t know if the picture would be released. I thought when this scene was done, if anyone wanted to know what it was like living in that world at that time, it’s like a time capsule. Just play this one scene to get a sense of the subculture of Sicilians, Neapolitans in downtown, not necessarily in the Bronx, but the east side. Some of the people who the characters were based upon were offended, understandably.

I grew up on Elizabeth Street in Little Italy in 1949. We were surrounded on the east by what they called Devil’s Mile, the Bowery. The West was called Murder Mile, Mulberry Street. Those were names given to those places over a period of decades, so they had to have elements of the dark side, and that’s where we grew up.

The Last Waltz

Music conjures up images in my head. It’s the most extraordinary feeling of freedom, the imagination and frisson in music that you respond to, all kinds of music. Here you have “Evangeline” by Emmylou Harris and The Band, being in America is amazing because you get the influence of all these different kinds of music, especially on the east coast. “Evangeline,” “The Wait,” and The Last Waltz itself were done and designed on paper, to music, shot-by-shot. All the drawings do exist. It wasn’t a situation where you have seven cameras and you select later. It was a matter of: the first shot was a tracking shot which ends on Emmylou and it comes around and you cut on a tracking shot from the rear… I’m sliding along to the music, sliding along to the guitars, and her voice is like an angel and you start soaring away.

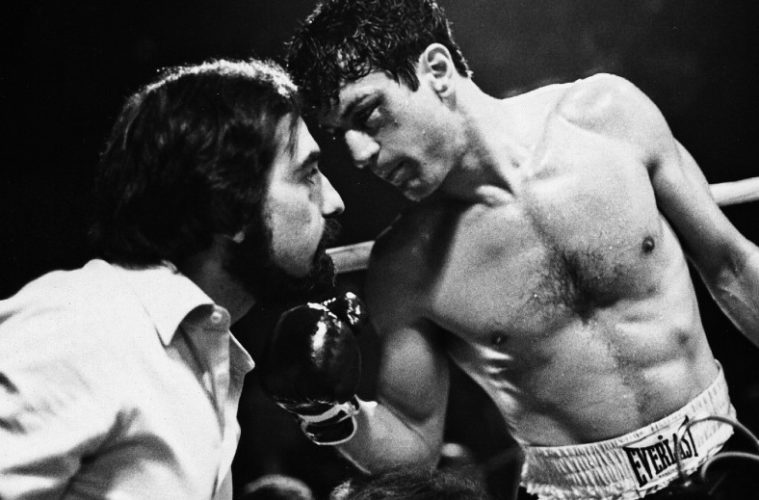

Raging Bull

I resisted Raging Bull for some time because I didn’t understand boxing. I didn’t have any experience with sports. But I realized it was about De Niro’s character and not about the boxing scenes. This character is so extraordinary that I thought the boxing scenes had to be special and I didn’t know… I designed the fights according to your choreography and I let the music move me. If you had four lefts and one right that was two bars of music. So what I did in The Last Waltz was applied to the boxing scenes.

Casino

There’s a gloss with the shot of the sunglasses with the car’s reflection. It was a three-hour film packed with music. I think up until that time it was the most expensive soundtrack ever, including that instrumental piece you heard on the car, George Delerue’s music for Godard’s Contempt, which has themes of prostitution, cinema, etc. We mixed it in with the drums of Ginger Baker of Cream. We started to pull themes from other movies.

In this scene, Joe’s language is like a jazz riff, it’s like music, music, music, and finally you’ve been warned. Bob’s character’s whole thing is the frozen look, trying to get a word in. Often a lot of people confuse something for good acting because they can see it; but when you think you’re not seeing it, that’s the big deal. The look on the face, the eyes. That’s why when a silent film is restored, the style, the acting—not all of them, believe me—in many of the great ones you can see this extraordinary expression in the actor’s faces.

Silence

In the middle is Shinya Tsukamoto, an avant-garde horror filmmaker, and the older one on the right is Yoshi Oida, who’s worked with Peter Brook for fifty years–he was eighty-two years old on that cross. The only thing he said he wouldn’t do is go in the water, but they wanted to stay on the cross and keep doing it. I was very concerned.

For me, the faith I was instilled with as a kid changes; it’s been a struggle towards a mature faith, whatever that is. This film took me a long time to pull together this story by Shūsaku Endō because I didn’t know how to write it based on the script by Jay Cocks. Ultimately, it’s about the struggle toward the very essence of faith–not certainty. The kind of thing I dealt with here [and also] in Kundun and The Last Temptation of Christ is not fashionable, but it doesn’t mean it isn’t true. It doesn’t mean we don’t do it with conviction. It doesn’t mean there isn’t room for it. Terrence Malick wrote me a letter [after seeing Silence], and he said “What does Christ want from us?”

Watch their full conversation from Tribeca here.