The return to Twin Peaks did not begin with this summer’s third, possibly final season of David Lynch and Mark Frost’s medium-shaking television project — despite what almost everything, from general public perception to the kind-of-sort-of-but-not-really subtitle, would have you believe — but through last year’s The Secret History of Twin Peaks, a visually dense, textually opaque epistolary novel penned by Frost. Though initially perplexing in scope (it begins with Lewis and Clark, folds the likes of Richard Nixon and L. Rob Hubbard into the Peaks mythos, and only hits the original series’ events at book’s end), it proved a more-or-less-perfect tee-up: plenty was said, seemingly nothing revealed — perhaps the most notable exception being the existence of Agent Tamara Preston, played in the new series by Chrysta Bell — and its tethers to events we’d eventually follow (or at least observe) week after week proved, in hindsight, rather deep.

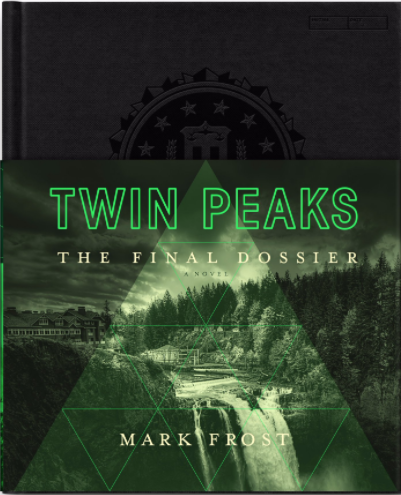

Frost has returned, post-finale, with a second and, judging by its title, more definitive text: Twin Peaks: The Final Dossier. The conceit, like the title, is only clean when taken on paper: Preston, following Gordon Cole’s demands, details the heretofore unknown events of characters’ lives in the 25-year span between season two and season three. It’s inevitable that bits and pieces will play as fan service, though much of what’s revealed is far darker, sadder, and all too real-seeming to register as catering to pure pleasure, regardless of satisfactions in quenching (certain, not all) curiosities and finally answering, to name but two obvious examples, “How’s Annie?” and the fate of Donna Hayward.

Complications begin springing up, eventually proving the book’s raison d’être: direct reckonings with the series and Fire Walk with Me are made, and while they may easily be taken as mere suggestions rather than answers, they are, no surprise, some of the more persuasive I’ve ever heard, and thus the sort that can’t be cast aside. The Final Dossier, like the show to which it’s inextricably linked yet manages to stand aside from in matters of perspective and tone, lets its many possibilities flourish by digging in clickbait articles claiming the book “unlocks” season three’s perplexing final hour are greatly exaggerated — as Frost himself says below, this is largely yet another “what if?” in a grand tapestry of “what if?” (On that note: yes, he and I already have a disagreement in interpretation.) I’m happy to be toyed with and play in this sandbox again, be it for the last time or as just another step along the journey.

The Film Stage: We saw, three years ago, an announcement of The Secret Lives of Twin Peaks, which was said to bridge the gap between the two shows – then we get The Secret History of Twin Peaks, which is not only different in approach, but, in fact, defiantly not what was promised. What happened along the way?

Mark Frost: Honestly, that was just due to an unvetted press release that went out prematurely and described one of the two books I was going to do – that being the second one, the first obviously being The Secret History. So it was no more complex or mysterious than that.

While writing The Final Dossier, had you seen footage from the new series? I’m thinking of Chrysta Bell, who brings an edge to the character that’s her own.

Yeah; I wrote The Final Dossier after we finished production.

I feel as though the character in the book has a different voice from the character in the series. Did writing for her after seeing Bell’s performance change your approach to or ideas about the character?

I feel as though the character in the book has a different voice from the character in the series. Did writing for her after seeing Bell’s performance change your approach to or ideas about the character?

No, it didn’t change it in the slightest. I had created the character with David in the script and elaborated upon it in The Secret History. So I think what you might be describing is simply the character in The Final Dossier is the character after having gone through the experience of The Return.

Why this character to anchor the stories? I read Secret History before seeing the show, The Final Dossier after, and the experiences were informative in how I think about this character. I’d like to know about your attraction to her as the center.

Well, she was the legacy character from the first book, so it made sense for her, then, within the framework of that task force, to be given the job that Gordon asks her to do. It felt like a logical extension of where we’d been with her role in The Secret History. And she’s a character who wasn’t familiar with Twin Peaks, so she was a stand-in for an audience that maybe didn’t know any of the material; and through her, you could filter your perceptions through the lens of hers.

You fold in so much of the Twin Peaks universe – not just the shows and film, but even references to your brother’s book, The Autobiography of FBI Special Agent Dale Cooper: My Life, My Tapes. Did you revisit it in preparation for this book?

No. I revisited it when we were working on the script, because I needed some reference points to Cooper’s backstory, and that was the most extensive work that had been done on his backstory, so I revisited it up to that point.

Is Lynch familiar with My Life, My Tapes?

I do not know that.

There are so many small character details, e.g. the fact that Jerry Horne built a giant, forest-disrupting speaker inside a cabin, that feel true to the characters. Had you thought of this and other similar material while writing the series, but had to excise for whatever reason? What is the balance between what was conjured up in that writing process and during production of The Final Dossier?

I’d say it was a mix. There’s nothing I can think of that we wrote for the script that subsequently didn’t make it and I included in the book later. But these are all characters, obviously, very familiar to me now, and it was more just a process of turning my imagination loose on what had happened to them in the intervening years.

Though I have to ask if, for instance, Donna’s fate was envisioned entirely on your own, or if that grew from discussions made while writing the series.

Um… no, I’d rather not speculate on that.

And the book envisions dark endings for most characters.

I would characterize it as “realistic.” Not everybody gets a happy ending; in fact, most people don’t. That’s what I was trying to convey.

Some have called the book a “conclusive narrative” to the show, but I feel like that’s not true at all – it doesn’t really answer so much as comment upon. Do you see this as more open-ended than “final” would indicate? And how might you strike that balance?

I would say that, particularly, those last chapters were an effort to expand and elaborate upon the ending of the show rather than make conclusive statements about it; it was fun to just kind of hold it and look at it from different angles. And, again, it’s looking at it from Agent Preston’s point-of-view, which is not privy to everything that happened in the show – she’s only looking at it through her own perceptions, which are a little more limited.

The Final Dossier‘s ending also allows, I think, room to interpret the new show — which, likes its predecessor, doesn’t follow traditional temporal continuity nor adherence to laws of logic — as its own closed circuit: the description of what happens after Cooper saves Laura — she’s pronounced missing, not dead; Cooper comes to town and, with no trace to follow, there isn’t much of a case to solve; for most people, life goes on as it did in the wake of her death — has a weird way of aligning precisely with what we’ve seen in season three: her father’s absence, her mother’s intense depression, the gap she still left in the town despite the change in her fate.

I wouldn’t say that… I mean, if the timeline is going to change, it doesn’t change until the end, so I don’t think anything that precedes the end — if you’re viewing the show as chronological in time and space, which I believe it more or less is — there would be no effects, retroactively, to material that happens before we see it; it would have to happen in sequence. So I’m not sure I entirely agree with your thesis there.

The show is, nevertheless, open to interpretation, and I love how one of the series’ few concrete places is in social and economic commentary. You’d said season three reacted to the recent world crises, and your Twitter account makes perfectly clear that you follow these things closely. Is the same true of Lynch? I wonder if you two had particular conversations about your reactions, and if these things are also part of his consciousness.

I think he’s got his own consciousness.

Well, absolutely. But do you know if he keeps up with these things the way you do? Because it comes through in the show.

No, I don’t think he’s as focused on those things as, perhaps, I am.

The melding of what’s written and shown is really beautiful. You’d expressed an attraction to Las Vegas, setting-wise, because of homes that had been built and then abandoned, and the way he and Peter Deming photograph it is rather haunting.

Well, he shot what we wrote. It’s in the script, so, for the most part, that’s the blueprint. But those things were spelled-out, to some extent – particularly in the Las Vegas scenes – and I thought he did a great job depicting them.

How much time did you spend on the set, and what was your response to seeing that depicted?

I was there about 40% of the time; the rest of the time I was working on Secret History. A set’s a set – you don’t really notice much on a set, and sets are all kind of the same, in a lot of ways. It’s basically a mobile factory that moves around and manufactures images and sounds. David runs a really good set. Aside from that, it’s a set.

I imagine there was a lot of soul-searching to figure out what Cyril Pons has been up to for 25 years.

Oh, yes — that took months.

It shows every second you’re onscreen.

Well, you know, you try to put your whole performance into every moment as much as you can.

At one moment you look alarmed; at another, you’re pointing at something.

I spent literally minutes thinking about it.

I was actually very happy to see him show up again.

Yeah. It was a bit of an Easter Egg, and it’s kind of fun to do.

Reports told us you and Lynch spent about a year working on the first two hours, then a year with the rest. There seems to be a big discrepancy, time- and length-wise. Was the opening just particularly tough to crack?

I wouldn’t say it was a whole year to write the two hours. What I meant by that was: it was a whole year before we started writing the script in earnest because it took, kind of, that long to cross the ts and dot the is on the deal with Showtime. The actual writing of those first two hours took, maybe, two or three months, and then there was a long period where we were waiting to see whether it was going to happen; and then it took about another year to do the rest. So I would refine the timeline that way.

Even thought it was constructed in one long film, did the first two hours still become something of a separate entity?

Well, we had to have something to show to Showtime; those first two hours had to function as a sales tool to get them to jump onboard. So I’d say that was the only distinction: we needed to cover enough of the story to give them enough information to make a decision.

And it ends, roughly, with Cooper getting out?

Yeah, more or less.

The screenplay for episode eight was said to be about twelve pages.

Yeah. My memory is twelve-to-fifteen pages.

And that the atomic bomb sequence was only about a paragraph. How much of that was written together, and how much of it was part of the material Lynch is said to have later written with your approval? And was it a particularly fun hour to write, standing out in your memory the way it’s since stood out for viewers?

We wrote it together. It was certainly different from a lot of the rest of the material, and it was challenging in that regard, but it was just part of the story on another level. So I wouldn’t say it was distinctly different, no.

There’s an inclination in contemporary storytelling to lay out things that don’t need to be laid-out. I love that it’s an origin story told with abstract images, and I’d like to hear about the processes of making that come to life. The book, for instance, makes clear that the girl at episode’s end is Sarah Palmer.

It’s just following a very basic tenet of moviemaking, which is to show and not tell. I guess one of the things we’ve always tried to do is not spell everything out for people. Our fans seem to enjoy having a chance to kind of wrestle with things on their own.

Do you know if the series exists as a single, 18-hour piece?

I don’t know; that would be a question for David.

Were you present for editing?

As much as I could, yeah.

Are you allowed to say, to what end, you had a hand in editing?

I’d rather not comment on that.

With the success of Twin Peaks, have you discussed relaunching On the Air?

Not… even for one second. But we have talked a little about getting it released as a DVD, so we’ll see what we can do about that.

That show has its fans.

Yeah, that’s what I’ve heard.

I will still make references to Bozeman’s Simplex; if somebody gets it, I know they’re to be trusted.

Yeah, no: it’s a very serious affliction.

Twin Peaks: The Final Dossier is now available.