When it comes to discussing his films, Paul Thomas Anderson doesn’t necessarily exude Terrence Malick levels of reclusiveness, but there’s a playful coyness to his interviews in which he insinuates he wants the viewer to have a pure viewing experience––whether that may be one’s first screening of one of his films or their 50th. With that knowledge, it means it is often from other sources where we get the most information about the making of his films, and we now have the definitive exploration of the cinematography behind his latest film, Phantom Thread.

In a 2.5-hour masterclass courtesy of Lux Lighting, First AC Erik Brown, Gaffer Jonny Franklin, and Lighting Cameraman Mike Bauman gathered to have an in-depth discussion of lighting the film, featuring a wealth of behind-the-scene video and images (pulled from a pool of over 11,000 stills Bauman took on set to judge exposure) detailing the production process. We’ve gathered the best bits from the conversation, but the entire talk embedded below is well worth watching, especially for anyone interested in the craft of cinematography.

Being Inspired by Stanley Kubrick

One of the first rumors coming from the set of Phantom Thread was that Paul Thomas Anderson would be acting as his own cinematographer for the film, which did turn out to be the case. However, for those looking through the end credits, you will not see the distinction. Rather, PTA was inspired by Stanley Kubrick’s credit of “Lighting Cameraman,” given to John Alcott on Barry Lyndon, and he gave that credit to his longtime gaffer Mike Bauman.

It wasn’t the only Kubrickian inspiration for the film as the team notes how the candle-lit scenes in Barry Lyndon was a major touchstone for Phantom Thread, particular in the bigger dinner scene later in the film, pictured above. They also commented on how the driving sequences––the distinctive camera setup for which was also a moment of impromptu planning by PTA––shared a connection with those from A Clockwork Orange.

Testing for Phantom Thread

Although Phantom Thread started shooting in January 2017, Paul Thomas Anderson and crew spent quite some time before that not only testing cameras and lenses, but also the setup for how this collaboration would work with PTA ascinematographer. They found the perfect avenue to do such tests were music videos, specifically with Radiohead and HAIM. The video for Daydreaming, Radiohead’s single from A Moon Shaped Pool, released in May 2016, was the first test with this camera crew setup.

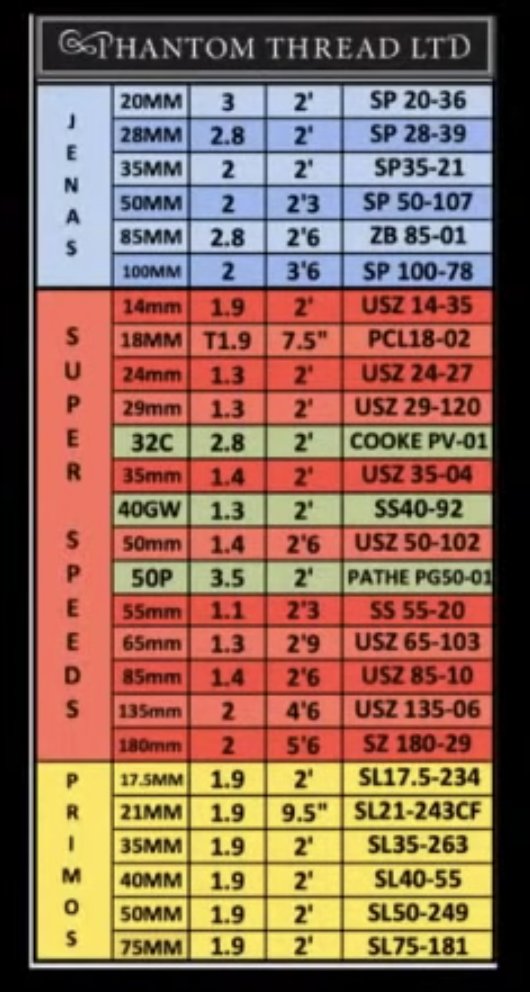

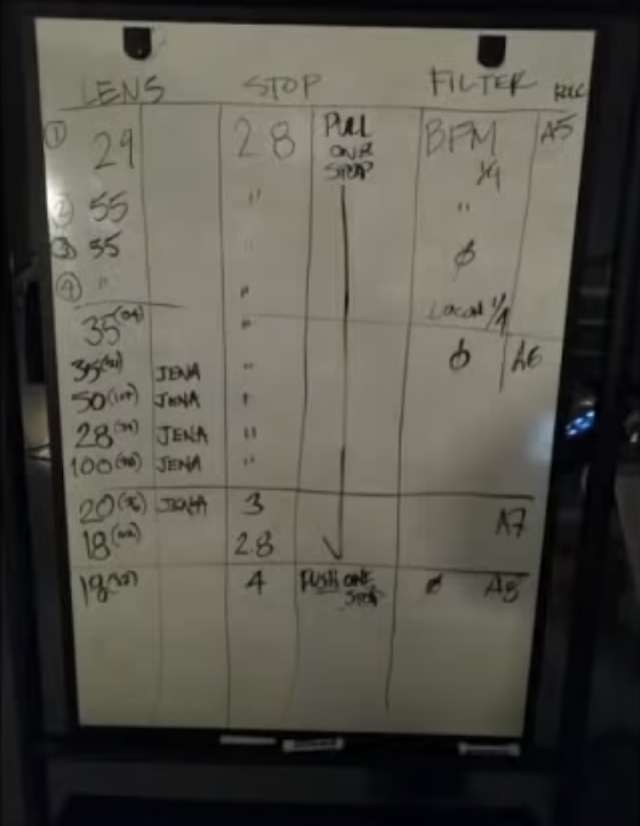

Paul Thomas Anderson is also “always testing” for what he may use in forthcoming films. He even tries out different lenses on other film sets, including The Master and Inherent Vice, as an opportunity to experiment for future use. The crew touched on how these camera tests may end up in the final cut, noting an example of Katherine Waterston camera tests in Inherent Vice. Based on this intense researched, a “bespoke” set of nearly 30 lenses were used on Phantom Thread, as seen below.

PTA Didn’t Want Phantom Thread to Look Like The Crown

When it comes to what kind of cinematography PTA didn’t want for the film, it was very clear. “There’s a lot of gorgeous photography out there when it comes to period films,” notes Bauman. “[But Paul Thomas Anderson] didn’t want it to be super glammed out and beautiful. It was all about ways to degrain the image.” Brown adds, “Paul’s reaction to [some of the camera tests] was, ‘It’s too beautiful. This looks like the fucking Crown. We’re not doing this.’ It’s beautifully done, but he didn’t to emulate that.” Brown went on to reveal that they even had to reshoot the first scenes of Reynolds’ dress-making in his atelier because even though it looked beautiful, it was not what PTA wanted.

Daniel Day-Lewis’ Method Approach

The dedication and preparation on the part of Daniel Day-Lewis should be no surprise to any viewer, and the cinematography crew confirmed that was the case for Phantom Thread. “As the stories are true, he embodies every character,” said Brown. “He was Reynolds Woodcock. I never once referred to him as ‘Daniel’ or ‘DDL’ anything. It was ‘Good morning, Mr. Woodcock. Good evening, Mr. Woodcock.'”

He goes on to tell a story: “I remember Daniel Day-Lewis, when he would [come on set], and that table was laid out with scissors and thread and other things, he would always set it up his way. There was a reason in his mind behind everything that was on there and why it was in that position. He would ask for certain things, like that prop you didn’t even know existed. It’s a very high level. It’s not just an actor showing up on set. “

If you’re looking for your own piece of lavish clothing, you only need to ask Reynolds Woodcock. “Daniel Day-Lewis can make a dress. He can measure anyone and make a dress for them,” said Bauman.

Happy Accidents

A moment in one of the best scenes in the film was a happy accident. “In this scene where we meet Vicky’s character Alma for the first time and the flirting is going on with Reynolds Woodcock, there’s a moment when she trips and then serves him the food,” notes Brown. “If you look, she’s very red. She’s very flush. That wasn’t a lighting trick. That was just real life intervening in the moment. She actually tripped and she was terribly embarrassed we were rolling on her and she completely blushed. It was so perfect for her character. It’s in the movie.”

One of the best shots of the film wasn’t an accident, per se, but it was entirely unplanned. The New Year’s Eve party scene featured many extras, lavish costumes, complex blocking, 1,000 lightbulbs to change, and numerous balloons. You can hear the team discuss how they felt about resetting the scene, but perhaps most interesting is a tidbit about the end of the sequence. The shot of Reynolds and Alma dancing by themselves after the chaos ended was completely improvised on the fly. As the extras left set and overtime kicked in, a reduced cast and crew pulled off the shot as envisioned by PTA in about 30 minutes.

The Difficult Shoot in The House of Woodcock

The House of Woodcock is as sacred a space in the film as it is in real life. Set in the Georgian square named Fitzroy Square in central London, this particular, historic building was under a strict code in which very little adjustments or additions could be done inside or outside the house for production. It was also five stories–with footage being shot in every square inch–and not only was there no elevator, but lifts for any equipment outside the house were not allowed.

“It [was] an incredible nightmare,” Franklin said. “Whoever the owner was previously essentially gutted the whole place, pulled out every single cable. All the heating, all the water was gone. It was just an empty carcass.” The crew had to create reports for every little thing they did. They were also supposed to only be shooting there for 30 days, but the shoot there lasted five weeks. Making the constraints even tighter, they could only shoot between the hours of 8 AM to 8 PM with no extensions given. This made one particularly memorable scene in the film quite difficult.

The fever dream scene in which Reynolds sees a vision of his mother “was finishing at 7:59 PM and you hear footsteps coming up the stairs saying you need to shut down,” Brown said. Bauman notes they would usually wrap filming around 7:50 PM to give themselves time to get ready for the nightly inspection, but on this evening, they wanted to finish the scene. While those keeping them in check were storming the gates and making their way up each new level, the rest of the camera crew was wrapping up, and not alerting that a small crew was finishing an intimate, emotionally poignant scene upstairs.

While they indeed got the shot, the next morning, Daniel Day-Lewis had some less than kind words to say to PTA and the producers… which they didn’t reveal in this conversation.

200 Feet of Dolly Track

Paul Thomas Anderson’s affinity for dolly tracks has been evident throughout this career. Following up 700 feet of dolly track in a scene for The Master (where Joaquin Phoenix is walking by the boat) and nearly 500 feet of dolly track for the “Journey Through the Past” scene in Inherent Vice, the scene that takes the dolly track cake for Phantom Thread is a special one: “Whatever you do, do it carefully.”

As seen in the images below, they used about 200 feet of dolly track to pull off the early-morning shot featuring Reynolds and Alma taking a sea-side walk, part of the first week of the shoot. It was “blistering cold.” There was no additional lighting. They simply prayed for the perfect sunrise, and they got their wish.

The Hardest Shot to Pull Off

When it comes to pulling focus “everything with Paul is difficult,” notes Brown. The crew joked that they often use the term “freeform jazz odyssey,” referencing This Is Spinal Tap, for PTA’s mode of production. “You don’t really have marks. You don’t have focus marks. You go with the flow.” Considering they wouldn’t see dailies for 3-6 days because of their remote shooting location, it proved to be a challenge to know if what they were capturing was worthwhile––particularly when it came to a scene late in the film.

“I think the hardest shot was at the end of the movie,” Brown said. “We were shooting the Barbara Rose wedding reception scene and at the very end of the day we had to run across the street at the park to shoot Alma and Reynolds walking with the baby carriage, the end of the movie. In typical film fashion, we were way late getting out there. We had almost lost all of the available light. It was beautiful, but it was a one time crack at the shot. Somebody else had set it up with the dolly track and second camera. So I ran out there at dusk. I didn’t have any tools. There was no remote focus. Push two stops, 2000 ASA, there’s no light left. We put the longest prime lens we had. It’s wide open. I’ve got no focus marks. There’s no light ranger. There’s no CineTape. There’s no nothing. We just shot. I had no marks. I didn’t know where they were walking. It was an absolute crapshoot… I really thought I probably didn’t have that shot in its entirety. That was without a doubt one of the hardest moments.”

Check out the full conversation below, along with camera tests. As for Paul Thomas Anderson’s next feature, they say the crew is “getting ready to gear up post-COVID” for the shoot to begin.

Update: The cinematography have published an hour-long addition to the talk, answering more questions. Watch below.

Phantom Thread is available on 4K/Blu-ray/DVD and digital.