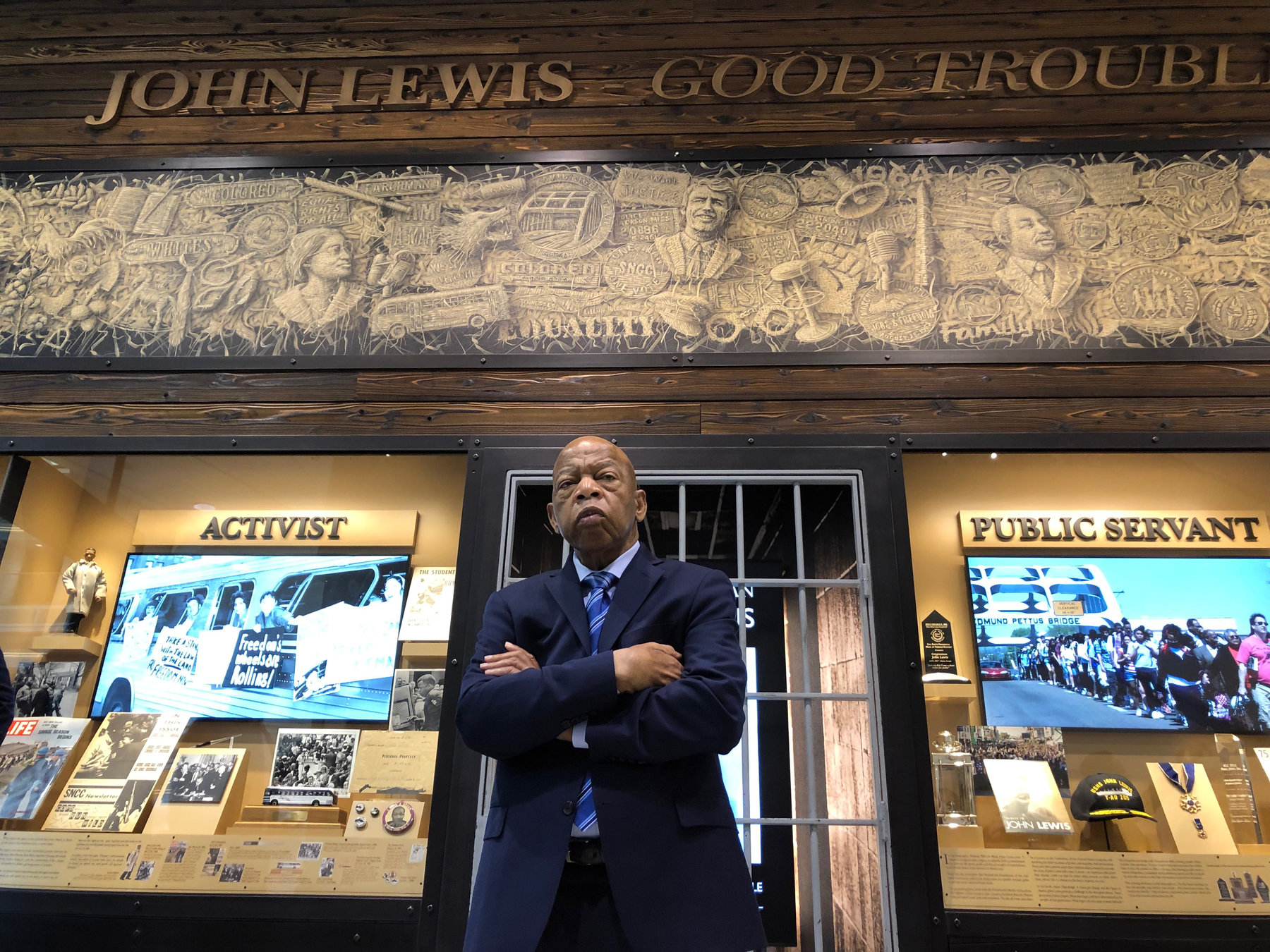

If it seems impossible to stay positive at this moment in history, look to the enduring spirit of John Lewis. The Georgia congressman, who has encountered all forms of adversity in his 80 years of life, has remained a smiling and resilient example of optimism in the face of hardship. It’s an enviable attribute that’s hard to miss in John Lewis: Good Trouble, Dawn Porter’s new documentary about the longtime civil rights activist and politician. In the midst of a global pandemic, and in the wake of America’s renewed and sustained reckoning with racial justice, what might otherwise be considered a hagiographic survey—similar in vein to the recent Ruth Bader Ginsburg documentary, RBG— has now taken on the added gravitas of current events and stark need for leadership.

Throughout this eight-decade portrait, little attention is spent on the current White House administration and its principal figure in the Oval Office. For better, and occasionally for worse, that specific subject—one of many impediments facing Lewis and the Democratic party—looms ambiguously. Instead, Porter aims a broader lens to highlight Lewis’s personal, ongoing fight to combat injustice, from his early days as a civil rights activist to his current office meetings in congress. “There are forces today trying to take us back to another time, and another dark period,” Lewis addresses the camera at the documentary’s beginning. “We’ve come so far, made so much progress, but as a nation and as a people, we’re not quite there yet.”

It’s an important reminder—Lewis’s life is by no means a closed book, but part of a relay race that he remains dedicated to winning. Through rare archival footage and recent digital material, Porter observes both the breadth of Lewis’s work and the urgency he brings to his daily campaign stops and meetings. Though he is most remembered for walking on the front lines across the Edmund Pettus Bridge during the Selma-to-Montgomery march in 1965, Lewis has been in the foreground of the entire civil rights movement. In 1960, he helped organize sit-ins in Nashville to fight for integrated restaurants; the next year, as a member of C.O.R.E, he joined freedom riders on dangerous bus trips into the south. Eventually the leader of SNCC in 1963, he spoke to the masses during the March on Washington, becoming an ally of Martin Luther King Jr., and several years later witnessed Robert F. Kennedy’s assasination, prompting a dive into politics.

Indeed, Lewis offers a unique prism through which to follow history. Raised in Troy, Alabama, picking cotton and preaching the bible to captive chickens on his family’s farm, Lewis felt called to do more than agrarian work. Eventually, he left his siblings to pursue education and absorb the nonviolent teachings of Rev. Jim Lawson, a pivotal juncture that shaped Lewis’s worldview. Despite worry from his mother, Lewis committed to taking part in peaceful demonstrations and protests, the “good trouble” he continually advocates for, which often put his life in danger. His staunch belief in nonviolence ultimately lost him his SNCC leadership position to Stokely Carmichael in 1967. But two decades later, Lewis channeled his spirit into the political sphere when he upset longtime friend and incumbent Julian Bond during a prickly campaign for one of Georgia’s seats in the House.

Most of Porter’s documentary splices this historical exegesis with close-ups of present-day encounters, which include campaigning for fellow Democrats in the lead-up to the 2018 midterm elections. Along with trusted chief of staff, Michael Collins, Lewis shakes hands and walks through large crowds, a celebrity at this point—he pauses for photos, signs autographs and briefly connects with fellow Southerners about their shared past. He plays an enthusiastic supporter for his party’s more progressive wing, rallying crowds for Beto O’Rourke, Stacey Abrams and Ayanna Pressley, while remaining a distinguished friend of long-standing democrats, such as Speaker Nancy Pelosi, Hillary Clinton, and the late Elijah Cummings. In this way, Good Trouble works as an addendum to Knock Down The House, the 2019 Netflix documentary about four young candidates—Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez among them—making their first bids for congress. Ocasio-Cortez, along with a host of other Democrats and politicians, family and friends, show up to share their thoughts on Lewis, his impact on their careers, and his persistent pursuit of justice.

At its best, Good Trouble offers a painful reminder that voter suppression continues to affect plenty of states and districts. Lewis’s courageous efforts in Selma to pass voting rights legislation 55 years ago remains a battle today—he urges crowds to stir up trouble, to make voter registration easier and more accessible—as racist policies disguise themselves in the form of gerrymandering and limited polling centers. But because Porter is concerned with Lewis’s entire arc—his family life and other roles in congress—the documentary’s emotional center loses the momentum that other, more focused examinations, like Ava DuVernay’s 13th, have achieved. Still, the packaged collection of his various accomplishments and causes near to him proves valuable, even as it slightly undercuts a more defined narrative.

The one closest to emerging might just be written in the future. Without a mention of 2020, nor Lewis’s recent cancer diagnosis, the fight to enact more substantial change has never been more urgent. Of his most notable achievements, Lewis’s ability to work across the aisle, over multiple presidential administrations, to sustain the Voting Rights Act of 1965 offers the best example of his leadership. Whether that Act will be renewed another time is a question that lingers, but its success will not hinge solely on Lewis now. As he perches from a chair in a dark theater—one of Porter’s filmic flourishes that gives Lewis a small, dramatic stage—the message becomes clear. “You have to be hopeful, optimistic” he says, a self-taught motto and a reminder to everyone taking on his fight.

John Lewis: Good Trouble is now available digitally.