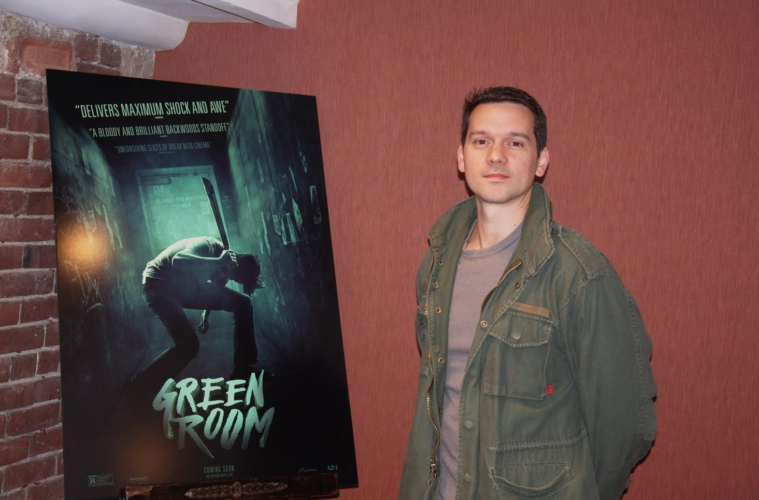

One of the most accomplished filmmakers to break into the American independent scene in recent years is Jeremy Saulnier, a NY-based writer/director who has been gaining serious momentum after the success of his 2014 revenge fable gone awry Blue Ruin. Saulnier has returned with an even more brutal thriller Green Room, about a group of punk rock musicians held captive in a skinhead club house after accidentally witnessing a a dead body. Relentlessly tense while balancing a constant sense of dread, the film encapsulates the essence of the interesting and compelling voice that sets Saulnier apart from the dime-a-dozen violent thrillers.

We were fortunate to sit down one-on-one with the director about his latest endeavor and discuss in detail some of the methods to his madness when he approaches a new project. From his writing habits to allowing actors to improvise on set, Saulnier delves deep into his inspiration behind the project, what made him decide to make another film outside the traditional studio system and how his personal history with the hardcore music scene influenced his desire to preserve the cultural scene on film.

The Film Stage: Can you describe your method for writing this script? Did you start by developing characters and paring the script down or by focusing on the structure and building from there?

Jeremy Saulnier: My method for writing is not even known to myself yet because I’m very intuitive and very practical in my approach as I’ve been just trying to generate material. This idea I’ve had for a long time, so I had the premise for almost 8 or 9 years, just shy of a decade. I definitely referred to my youth and my experiences and the people I knew in the hardcore scene, my bandmates. So building the band was easy because I had people to refer to and I had my own experiences in the hardcore scene and I injected all that into the characters. But also, I don’t do a lot of exposition or contrived back story. I think there is depth to them but surface level as far as my approach, I don’t need to know their full history, I just need to know who they are and then they just behave as I think they should.

I definitely try to inhabit the characters and play a bit with that but I don’t allow any false injections of contrived backstory or exposition or artificial conflict. That drives me crazy too, like “let’s just have more tension randomly.” If it doesn’t have tension coming, a lot of bands I knew they were all in it because they wanted to be there. You’re road wary and bitching about who’s going to pay for gas and these little things come up. For the band I needed some cohesion and some camaraderie to start the film. As far as the process, it’s a rare thing that this is a relatively unfiltered screenplay. I was able to be very intuitive and as I was writing I would just be surprised. I would find myself without an option, so someone would die, like I didn’t have a way out so neither did they. It was not all planned, it was just a general arc and feel and I knew where the film would start and roughly where it would end, but getting there was really fun and kind of mathematical. I love problem solving and staying true to my intuition and not my intellect — that’s how I get to be surprised by my own writing. I let things evolve in a haphazard way that’s very grounded and disregards the rules of screenwriting structure and formula.

Do you sometimes rely on the actors’ performances to improvise on scenes? For example, did you let Patrick Stewart add any nuance to his character Darcy?

Dialogue wise we were locked in. There wasn’t much to do. The funniest thing was Patrick added one little line of dialogue, it was the word ‘fuck’ and it was under his breath and it was between other lines and it’s was the fulcrum of the movie. Everything is turning and he’s making a huge decision and he mutters fuck under his breath and it was my favorite line of the movie. It’s so great how that one little detail is like, “Oh, come on we shouldn’t do that. Oh, actually, wait Patrick, but that’s kind of perfect.” There wasn’t a lot of room for improvisation as far as the spoken word, but there’s a whole lot of room given to the actors for the emotional continuity that they would need to manage over the course of the shoot. That was fun in that they trusted me as a screenwriter and director and I trusted them completely as actors because there was so much room for interpretation of performance. And we occasionally cut a line or tweak it if it sounded false, because when you have someone actually speaking your dialogue it’s the easiest way to smell a rat and be like that’s a bad line.

Or I would have to tell them what their line actually means, because they would say something that doesn’t quite make sense and the inflection would change just naturally. It’s hyper-detailed; if you just take a random page of the script it seems like all throw-away dialogue but the key is that every single utterance means something important and to get through every narrative beat and every intention I had fantastic partners. I lost sight of it sometimes when we were on set, deconstructing the script and shooting just single lines or whatever it is. Then only when we edited the finished film, the last pass, the tightening up of all the dialogue, the overlapping, the haphazard nature. It seems improvisational and blurted out, but at the 11th hour the intention of the script was realized. It was tough for awhile. When you have just 6 frames too long — a pause between these lines — they all of sudden make no sense, they have no intention. When you dial it into technical perfection, all of sudden the unbridled chaos becomes clear.

Can you discuss your personal experience in the hardcore music scene and how this affected making Green Room?

I started as a skateboarder and there’s an obvious association with punk in skating, especially in the mid 80’s when I was skating. I would be around cooler older kids and they would have t-shirts and I would see what they were and I would ask my mom to take me to the store and ask her to buy me records blind. I would listen to the on cassette primarily. I was experimenting with punk rock and skateboarding, so there’s always this physical association with punk and that is how I become so attracted to it, is the physical element of it. The performance level, being in the slam pit, it’s really an amazing outlet for energy. I loved being part of the scene but I was not an archivist, I don’t have a ton of vinyl, I can’t name drop a thousand bands. I just was there and enjoyed being there but wasn’t precious about it. It totally affected me and will for the rest of my life as far as my influences in my formative years.

The other thing is the aesthetic of it. I loved the subculture and how it looked and felt. It’s always evolving, thousands of subgenres of metal, punk, hardcore you could find. You could find your tribe no matter what, but within a general subculture it was one of the most diverse. I was attracted to the more aggressive side of the music. I loved metal and just felt I needed to harness that power. As I got older and more into the film, I felt this inevitable connection and I could never find closure on that experience and I had to archive it. And this is my way, I don’t have many old records or cassettes. My friends are more the tastemakers who would introduce me to bands. They would write music for the bands I was in. I was just a singer. I wrote a few songs but primarily I was just a mouthpiece and there to have fun. I was very grateful to be in their band and yeah, this was a perfect way to express my love of the scene and also my distance from the scene. Even when I was there I didn’t feel like I was an authority — I felt like a wallflower and somewhat of an imposter. The fictional band in Green Room, they perform songs that my friends wrote in high school and that’s really cool. It’s a literal archive of some of the songs that I grew up listening to.

After the success of Blue Ruin, were you offered any big-budget projects or did you want to stay working on a smaller scale?

I definitely was entertaining the idea. I had a lot of offers or submissions. I didn’t quite know if they were real deal or just development fluff. Development is a hard concept for me to grasp. There’s a lot of commerce and energy that goes into not making movies and I didn’t want to be part of that. I felt if I had momentum from Blue Ruin the last thing I want to do is keep that studio game of development. I’ve had friends who have had a certain level of success and they kind of take the bait and get involved, but there is no guarantee that film is getting made and you can end up doing two-to-three years of development then all of sudden you’re back at square one. You’ve got to re-introduce yourself to the industry as a director which takes a lot of trouble.

So I said, I’m just going to make this movie, I’m going to write it myself and I’m going to shoot it this year and it was almost an exact year from page one to when I wrapped production which is a rapid-fire process. I did it because I knew that I didn’t trust my environment and I needed to capitalize on the success of Blue Ruin to con people into making another movie with me and I didn’t want to make Green Room in two years. It’s probably my most aggressive and brutal movie I’ll ever make. It’s super intense and hyper violent in some ways and I knew it was a film I had to make but I was worried I was getting too soft to make it. So I gave myself a self-imposed deadline, which is how I’ve gotten any film made, was the fall of 2014 and it was make or break. Either I make the movie or it never gets made and that’s exciting when you set the terms and force people to get on board. We had some pretty enthusiast collaborators, but it got pretty scary there, but it was hell or high water. There was no way I would make it in 5 or 6 years. I would be too lame.

Is there any thematic connection with the color palettes of your film?

It honestly just happened to line up. Blue Ruin had the beach and blue sedan that was already blue before I came up with the title; maybe it was named after the car, I don’t even know where these things come from. But Green Room predates Blue Ruin and if the backstage holding room at a concert venue was known as another name, that would be the name of the film. With the punk rock movement, you have a lot of surplus clothing, a lot of green and army clothes. In Oregon you cannot avoid green so that became a part of the palette but not symbolic of anything specific. Blue Ruin was definitely a contrived palette, but it actually ended up being very warm and went from cool neutrals and tans, blues and greens and modern neon sources from the beach and transitioned to earthy colors, browns and oranges and greens at the end. With Green Room we were just trying to be native to the environment and then also color temperature wise with the lighting, have a little diversity in there.

So there’s no plans for an RGB trilogy?

There’s no RGB trilogy, but I make up shit all the time. One is the cluster fuck trilogy, that’s already done with Murder Party, Blue Ruin and Green Room. It’s also the inept protagonist trilogy, but I think the inept protagonist is an on-going theme that I never let go because I really gravitate towards that. But for now, let’s call this the cluster fuck trilogy.

Green Room is now in limited release and expanding. See a talk with Saulnier above, and watch him analyze a scene.