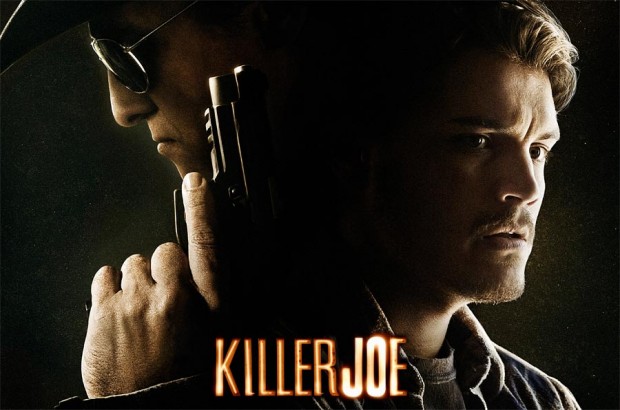

William Friedkin‘s latest, Killer Joe, is a gritty, trailer-trash madhouse that builds to a climax that is superbly sudden and unexpected. The SXSW premiere was filled with gasps and lots of dark laughter. The following day I was able to sit down for roundtables with the cast and crew and below you can find the results from our talk with Matthew McConaughey and Tracy Letts, as the film heads into limited release this week. We discuss fight sequences, inspirations, the way Friedkin likes to use one shot and move on, and much more.

The Film Stage: We were talking a little bit about the difference in terms of screening here versus screening in Toronto and Venice. Were you both at those screenings as well?

Matthew McConaughey: I was not.

Tracy Letts: I was at all three, and it’s played very differently at all three places. Venice was very quiet – there may have been translation issues there. And Toronto was not quiet, but not as raucous as Austin was last night. Austin was a pretty rockin’ response.

Was there a similar response to the play itself when it’s performed in theaters?

You know, it’s a different experience – movies and plays are just really different. And when you’re in a small theater and you’re watching some of those things unfold, it’s…film gives you a bit more distance. And the distance can be ironic. And so I think the laughs actually come a bit easier in the movie than they do in the play. Quite often when the play is performed – in the chicken leg scene, for instance – there is no laughter at all. They’re quite scared by what’s going on. So it just plays very differently in the cinema.

There’s this really interesting dichotomy to Joe where you see this kind of coolness about him but inside he’s very much an animal. And you also see him be quiet. Did you and Mr. Friedkin kind of talk about that?

MM: Yeah. We talked about this, we were talking about it earlier. Order and structure and family are the three major things for Joe. Mind you, what he does can be very animalistic or horrific, but it’s a business. This is what he does, and [these] are the rules, and this is how, you know, if things get thrown out of order he has to re-tilt the scale to get it back in order. Or try to. And in a very destructive way. So kind of the first two-thirds – in general sweeps, the first two acts – were keeping things very internal, and then when it’s time to really at a moment go outward, we would just steamroll that all the way through. Which all happens in the trailer – all in one long scene, really.

Gina [Gershon] and Emile [Hirsch] kind of talked about how Friedkin was very smart about how he shot inside the trailer itself. They said that they could pull away a wall and then shoot from that angle – you know, different things like that. But they also confirmed that it still felt cramped, it still felt very close quarters. How did you feel about that situation – shooting in an actual trailer, even though it was built on a set and things like that?

MM: Well, [with] the walls blown out – to make movies, people do that a lot. Like, in U-571, we were on a submarine, and they’re just on gimbels and you pull half of it out. A lot of times they’ll build things larger than scale just so you do have more room to move around. [But] this was pretty close to scale to a double-wide. It was pretty damn close to scale to a double-wide. And everything really takes place in the living room, and mainly in the kitchen. And some things outside. There’s some very still stuff going on in [Juno Temple’s character] Dottie’s room. And then I think the only time you see their bedroom is when Joe goes there and takes the clothes and clears him. It smelled like that trailer looked like. [Laughs.]

And after all, even if it’s fake rain in the studio, the mildew starts to add up. So as soon as you stepped on – a blessing is like if you stepped on there and you go, “Oh, we’re in it. Someone could turn the camera on at any time now, so be your man.” And I guess what I mean by that – and I’ve said this in different ways with different films – is it’s very nice when you go to work and there’s not a real line between, like, you’re behind the camera and you’re talking, and now go around – [and] it’s precious. You walked in, it was intimate, you were on it as soon as you were on it. It was packed with people a lot of times. I personally would hang out on that couch or on that set a lot just because it was nice not knowing what time of day it was and talking there and hanging out.

TL: Billy is really good at moving the camera around those spaces like that. I remind people that he made the film of The Birthday Party, based on a play by Harold Pinter. He made the film of The Boys in the Band. I mean, he’s got some experience in translating these small spaces into cinematic language.

What made you decide to translate this from the stage to film?

TL: I wanted to see the movie made. [Laughs.] I wanted to make a movie. I wanted to work with Billy again. We had such a good time on Bug. We really enjoyed each other’s company and found we were of like minds and of like tastes. And this had been kicking around for twenty years. The play is over twenty years old. Been kicking it around for a long time, people talking about making this into a movie. I can’t tell you all the different – it’s been through the ringer out in Hollywood. But Billy is a guy who does what he says he’s going to do, and he said, “Oh, I want to make a movie out of this.” And, boom, it happened. He’s a man of his word. And he got the thing put together. So I wanted to see it happen so I could see this thing reach a larger audience than I can reach in a theater and see an audience full of people in Austin, Texas enjoying the story.

Were you there on set while it was being filmed?

TL: Never, no. I was doing a play at the time, so I wasn’t there. But you know, I was never on set for Bug either. I think it’s probably better in a way. I would just be there pulling on Billy’s sleeve saying, “Hey, he didn’t say that line quite the way I wrote [it].” [Laughs.] I don’t think that would necessarily help anybody, [so] it’s probably better. Writers can be precious about that kind of thing.

Matthew, I saw Bernie the other day, and the contrast in being an authority figure in Bernie and then this authority figure of a totally different stripe. Can you – without giving away too much to people who haven’t seen Bernie yet – the contrast there? How close were they filmed together?

I think I left New Orleans – I don’t know, I think it was within a month I came back from New Orleans to Austin and then went to Bastrop and shot that. I don’t know how to compare the two, they’re two very different characters. Bernie is based on a true story about what happened in Carthage. And Rick’s a guy who I’ve worked with three times and he pitched the character. He said, “I got this movie, I got this guy” – kind of just like what he did the first time, “I got this movie, I got this guy, you just might be right for it.” [Laughs.] Now I’ve known Rick well enough where I’m like, he’s one of the guys that I can go, “Well, I’m in. Now let’s go talk about it. Let me go read it and let’s go work on it.” And we’ll talk more about that probably in the next couple days.

In the film, Dottie says Joe’s eyes hurt. Why do they hurt?

TL: Well, I don’t know. [Laughs.]

Is it just a funny line?

TL: No. I think it’s up for – somebody said to me last night, “Is it because she sees that there’s some pain in his past or something?” I said, “Well that’s a good explanation.” But I think there are a number of interpretations that might all be [good] – but I don’t have an explanation for it.

Did you come up with an explanation for yourself?

MM: I mean, I don’t know. [Laughs.]

Obviously a lot of fight scenes are filmed, you know, guys with guys – or even, in certain terms, girls with girls.

TL: What are those movies? [Laughs.]

Did you talk with Gina [Gershon] before the sequences? It very much looks like her – no stunt doubles? Nothing like that?

MM: No, no. No stunt doubles.

So did you have conversations with her about that or did you all just go in and do it?

MM: Those scenes are partially about – you kind of have to be athletic. It’s a spatial sense thing. How you line that up, and let’s get the distance because when you’re in the moment and you’re doing it you don’t want to screw up and go long. Or you’re doing it and the [camera] isn’t right – you go, “No, we saw it, you came up short.” And then if you’re going to go, you kind of walk through and kind of say, “Can I get up to speed?” [Then] you go half speed and you’re rehearsing and you go down here…and up here…and then take you to there…so if we go through there…you got to flip the table…maybe I flip it on the way, maybe I don’t. We got to get back to the counter…slam against the counter here. Well, all right, let’s bring in some rubber tape against the back here because if the back goes up against that – or do you need a back plate from the stunt man? So you kind of go through where your problem is going to be. There are spots in there where I knew my shins were going to get hacked up and I had things on my shins. So you just try and protect a certain few areas that you know you’re going to hit. [But] don’t get too technical about where exactly you’re going to be because you don’t want to be aiming for it or thinking about it. But you kind of protect “the spaces,” meaning, like, if we’re going to come over and slam someone on this table, well, let’s make sure these aren’t real glasses because these glasses could break.

And then you kind of walk through it. Lay her down over there against the sink and then you’re going to get around the neck – we’ve all seen the movies where you go, “They’re not really choking him.” So, partially, that’s much more to do with the person receiving it, and the great stunt trick is you get your hands here and pull. ‘Cause then they can act like their straining but you can just be like that. So there are little tricks that you learn along the way that I find fun. Because they’re kind of stunts, and the thing with these is…you know, a really good, and this is the same kind of violence, that domestic violence – you ever see Lee Tamahori’s Once Were Warriors? It’s a couple of shots, a couple of good blows and that’s it. It’s not the big street fight that goes on for twenty minutes – those movies you’ve been seeing. [Laughs.] And so it was in a contained space. And then there are these great ways to edit it. Like, when Joe throws that punch and hits her, it’s, “Oh shit, this just took a turn.”

And that’s sound – there’s great sound in what happens – [and] whatever frequency that is, that hit, it’s good sound. Not-as-good sound, which we’ve seen, doesn’t have near the impact. It’s also the editing – that it’s a surprise, it catches you. You don’t anticipate it coming. So going into that we were very sure about Joe [needing] to be very deliberate, act normal, going easy, seeing what we’ve seen, take his watch off as she comes up – and then it turns. And you just walk through it. You get spatial sense. And if someone’s too close, all of the sudden in the middle of the take, you have to stop in the middle. You don’t carry on if you turn and there they are. You go, “We’ve got to go back to the mark,” and you just reset. Because the last thing you want to do is – and you come out of them with…I had some blood on me. Wasn’t hers, it was mine. [Laughs.] But things happen and you just walk through it and get your major sort of scenarios and then do it.

Can you continue that on to the chicken bone scene? How did you feel as an actor in the sense of being this dominant force?

MM: Well it was one of those “go for it” scenes, that’s for sure. You put a pin in it and go, “This is going to be really scary and really fun.” It’s one of those – and this character had a lot of [them] in the third act – it’s not one of those scenes where you go, “Well let’s put a ceiling on it.” Everyone – her, me – wasn’t talking about the scene but we knew it was coming, and here it is, so let’s blow the top off. And in my mind I think a question was – and I don’t know if it was a question, but it was always in my mind – well, let’s play it where Joe actually physically does [this]. And the clinging moment, or whatever you want to call it. Anyway, so we said, “Let’s go [there]. Let’s do it.” And we just shot it and did it, and then all of a sudden, as soon as we yelled cut, everyone was howling and laughing. [Laughs.] And I dropped down and Gina was like, “Are you okay?” And I said, “I’m fine, just let me catch my breath.” [Laughs.]

We talked a little bit in the last conversation about the length of the scenes and them being very long scenes, not doing a lot of takes. Had you done work like that before?

MM: No, this was the beginning. Not the beginning – I’ve done some other ones – but not like this. This was really getting on it. And that’s intimidating if you haven’t done it before. Now it’s actually kind of become a preference for me. Just for, if you know you’ve got five takes, there’s something in the human body that kind of strolls through the first couple. But if you know, “No, this is it,” you get up to speed. [It’s] like a survival mechanism. Bring it now. It’s actually a good lesson, because I’ll go all day just for the fun of it. [I’ll] do fifty takes if the director wants to. But it’s not really necessary. And if people know what they’re doing, and you have a few rehearsals, the first one’s usually the best. Unless you just completely – you know, there are times when you just go, “Eh, I caught myself acting, can I get one more please?” And [then] it’s, “Yep, go. Do it again.” [But] it’s fun doing one or two. It’s vital. And there’s a certain energy on the set, from the camera department to everybody. We’re all in it. It’s live. This is our one time.

You have kind of an athletic background. Did it feel like playing a sport where this is “this play” and we have to get it right?

MM: I mean – I don’t know. I always try to – I like to do it right. I like to win. To run the race we’re supposed to be running. I learned very early that that doesn’t mean you hit grand slams every scene. [Laughs.] I’ve had some performances where I’m like, “Geez, it feels like I’m hitting a grand slam every time,” and [everyone’s] like, “Yeah, hon, you just need to get some bunts and some singles and a double.” [Laughs.] But the athletic part goes to the action sequences [I was talking about] – spatial senses and being able to sell those. And that’s very fun. I enjoy that because it has nothing to do with the mind. You kind of feel it. And it’s movement. I like movement. And even in violent scenes like that, they can be done with grace and yet still look like they’re out of control. It’s all somewhat choreographed.

You’ve worked for some really fantastic filmmakers this past year – with Jeff Nichols, Mr. Friedkin, Mr. Linklater, Mr. Soderbergh. Is there one through-line you noticed in terms of collaboration and also what makes a good film?

MM: In different way, Billy said it last night – if you’ve got the material, and you cast the right people, back out of the way. Let it [roll]. Let it go. Let ‘em run. Every actor wants to come in on fire and feel like they got sixteen lanes in the direction they’re going, and if you’ve got a good idea I’d love to hear it, but we don’t want to talk about this. [Just] shoot it. And if you get an actor that gets a line – a direction they’re going in, and they’re on fire – you just want to let them go. The best directors I work with let that happen. I’ve [also] worked with directors where it’s going great and they just feel like all of a sudden, “Man, I’ve got to go implement myself. Or [else] I’m not directing. So I have to go interrupt this thing and say something intellectual.” If it’s going – if it’s on a line – and it’s working, then maybe it’s a little different than it was conceived in their head.

But if you go, “Man, that got me from A to B and it’s different, but I buy it, and it’s true”…Of all the ones you brought up, Jeff [Nicols] would be the most linear – “This adds up to this.” [Steven] Soderbergh, again, is just one take, look over, next. [Laughs.] Rick’s very much like, “Yeah. Yep. Want another one?” Or if you go, “This isn’t quite hitting the screws,” [he’ll] go “Yeah, let’s talk about it.” Billy would throw in certain things, but Billy and I didn’t have a lot of conversation. We got that down before we started shooting. We got that done in rehearsals, we got that done beforehand. And I think, by the time you’re there shooting, I suppose every good director would want to be telling their actors, “You got it. What do you want me to do? We already did that work. We already went through that.”

I’ve heard some actors talk about how, when they shoot a movie and then finally sit down and watch the finished, edited version of it, sometimes it doesn’t match up with what was playing in their head. But with this film it almost seems as if maybe it does in a way because of the fact that there are so many one-shot takes, on go-through and then that’s it. He doesn’t have other secrets.

MM: True. Okay, true. If you go on and you got somebody that’s doing ten takes – I suppose if you’re working with [David] Fincher, who’s doing a lot more than that – you’re going, “Wow, what movie are they going to make?” I didn’t have that. We weren’t laying out a bunch of options and Billy didn’t have four films he could get back in the editing room to make. I’ve had movies – I remember back on TV and Ron Howard was like, “I could make four films. First cut’s four and a half hours.” Well, which one are you going to make? [Laughs.] The thing with acting is that the first time you go to see it is always pretty tough. Each frame is like a history lesson. You go back in time and you remember everything that day and you’re doing the math, and they you’re into the next frame. So you’re not really a voyeur sitting back and watching. But this one – that’s a good point. We knew what was laid down. We didn’t have too many options. We didn’t do it in Spanish. [Laughs.] We didn’t wear the red boots in one scene and the yellow boots in the other. [Laughs.]

Tracy, how much influence does James Ellroy or Jim Thompson – ?

TL: Jim Thompson, absolutely. From Oklahoma, Like I Am – I was reading a lot of that stuff when I wrote this. But, yeah, Jim Thompson definitely.

You also have a kind of Ellroy vibe going on where he’s got the real sharp – especially with Killer Joe’s character – this staccato, in-and-out type vibe.

TL: Some of that is just good-old-fashioned pulp fiction, crime fiction. Raymond Chandler, all that stuff. It’s just those certain things in the language, an edge to the characters. That’s why people are attracted to this, I think, in some ways. Beyond the genre elements, the need of the characters is right there – it’s out in front. And in characters like these, they may not all five of them be the smartest people you’d deal with, but when they feel stuff they feel it really strongly. So there’s a lot of feeling, there’s a lot of emotion and need up on the screen, which I think makes for more compelling stories.

Killer Joe hits limited theaters on Friday, July 27th.