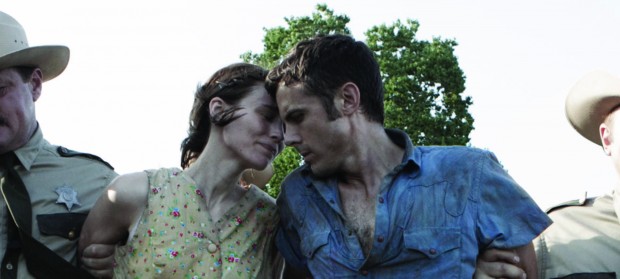

Premiering at Sundance Film Festival 2013, writer/director David Lowery has crafted a subdued, slow-burn drama with Ain’t Them Bodies Saints, one that aches with excellent performances from its ensemble, which includes Rooney Mara, Casey Affleck, Ben Foster, Nate Parker and Keith Carradine. Following the aftermath of a crime-filled life, the film skirts around the major peaks one may find in another drama of its kind, instead focusing on quiet, sublime exchanges.

We got a chance to sit down with the filmmaker during the festival to discuss his latest project, including how it came to be, as well as the editing process, crafting the beautiful score, the cinematography, production design and more. We also dive into his influences, which include Paul Thomas Anderson, Robert Altman, Apichatpong Weerasethakul and even a touch of David Cronenberg and the Coens. Lowery also helped out with two other Sundance features, Shane Carruth‘s Upstream Color and Yen Tan‘s Pit Stop, and we discuss his process with the former, so check out the complete conversation below.

The Film Stage: From what I understand this project had a different iteration in the beginning. Can you talk about how that process was, when you realized that the script started getting attention?

David Lowery: It was always going to be the same script but my original plan was to make it very low budget, very guerilla style, and just scrape together whatever funding we could, to just make it in a very tiny fashion. At a certain point I was advised (along with my producers) to consider that a really good plan B, whether the script was good enough to potentially warrant an expanding of our horizons. So we took that to heart and decided “Let’s try to see what would happen, what will happen” and we knew that we could always go back to making it that tiny, guerilla way that we intended in the beginning. So we joined forces with some other producers, Jay Van Hoy, Lars Knudsen, Amy Kaufman, who had read the script and wanted to just help out however they could and it went from being, “What do you think? Do you have any advice?” to “Hey let’s all team up and work together!” And through them the project picked up a little bit of steam; and they have done other movies and have outlets and resources that we didn’t have and were able to start getting it out to people. It got to an agent in WME and Craig Kestel who then was really excited about that and my short film and started sending it to actors. From there where he was like, “Do you want to? Who would you like to send it to?” and it was a very quick response. It was while I was here last year that I got a phone call that I needed to go to LA to start meeting some people.

Was the main cast the initial cast you met?

Yeah, the first people we met are the people in the movie.

And so you’re on set the first day with a bigger budget than I assume you ever imagined. Did you feel a little more in control?

You know, I was wondering that myself because I didn’t know completely what to expect and ultimately I had complete control. From day one of preparing the production I talked to almost all the crew members, all the key crew members. I only hired people I had a good gut instinct on and that I knew I could communicate with and be a good collaborator with. I felt in spite of the size of the film the fact that we had trucks and drivers and all that…I think that’s the thing that makes it feel bigger; that you just have all these people to drive trucks around and have trucks, rather than having everything piled into a van. You have a big 18 wheeler full of gear but then once you get used to that (which you do very quickly) it doesn’t feel that different from making a $12,000 film or a tiny little short film. The techniques and the tricks of the trade, so to speak, are all the same and you just put your head down and start trying to make a really good movie.

In a post-screening Q&A you said the script cuts out the big moments and I’m always sucker for those kind of movies. Were those things in the script or in an outline? Did you have those big moments there and then pared them down a little as you filmed?

No, I never had any of them and in fact, the first version of the script didn’t even have the shoot-out in the beginning. It started out with Casey [Affleck]’s character already in jail, and I was like, “I think we need a little bit at the beginning.”

So did you find that prologue before the title, did you find that in the editing?

No, that was definitely written. I really like the idea of having a big prologue. The title hits almost fifteen minutes into the movie, and I like the idea of having a lot of stuff happen really fast and very quickly and covering a lot of ground. Then it just slows down, and that was always the intention.

I have to ask about the score. It adds to the folk song-esque title and it adds a lyrical feel. Those hand claps, how did they come about?

Daniel Hart, the composer, is a really good friend of mine. And he worked with me on my first feature, St. Nick, and then on my short film, Pioneer. He’s someone who I very quickly realized that I could just tell him what the movie was about or show him a picture and he would know what to write. I think that’s a very rare thing with any collaborator. That’s what you’re always after, having that sort of shared wavelength and he and I had that right away. So, for this film he read the script (and got it of course) and came down to set and watched us shoot some scenes and watched all the dailies, not all but some of them. I described certain [music]; I’m a big fan of Joanna Newsom who’s one of my favorite musicians. There’s a video of her playing one of her songs live and there was one part where I was like, “I always that it would be amazing to have a scene with a score that sounds like that”. That was about as specific as I got, I just like the way that stuff sounds. So he went off while we were editing, like two weeks in, sent me a first track of music and it was the piece that plays at the beginning of the movie when Casey goes to jail and he writes his first letter and all of a sudden you just start hearing those hand claps and I was like, “Ok, you did it. This is great!” That’s in the movie. It hasn’t really changed, and that became a motif because it was so strong and something I’ve never heard before; and just completely captured the tone I wanted.

When it comes to the cinematography, I loved how the camera was always slowly gliding. Was there any storyboarding at all?

When it comes to the cinematography, I loved how the camera was always slowly gliding. Was there any storyboarding at all?

It wasn’t storyboarding, but I shot listed it to a certain degree beforehand and I just really love finding a point of focus and I think camera movements are great for that because whether it’s a zoom or a dolly, I love just being directed where I’m supposed to look and you can do that without moving the camera too but it just adds a degree of intentionality when the camera starts moving and it’s also just dynamic. I like it. Also, especially that scene with Casey and Keith Carradine, where we have a lot of ground to cover, he’s on one side of the shot, Keith’s on the other and it’s going to get more and more intense as it goes along. We were really able to turn it into choreography with the camera and that was something we started doing more and more, just figuring out a way. Ben Foster described it the best, “you’re dancing with the lens.” That’s what we really began to do more and more as the film went on. There’s always an intention behind it, we never moved it just to move it, we always had a reason. Then, when the camera doesn’t move there’s very specific points where it’s like here’s a shot that we’re going to hold and we’re not going to move and that’s again for a reason. I always try to (at least on some ephemeral level) be able to explain why it should or shouldn’t be moving.

One shot that stood out to me in particular, one that tells you everything need to know about Rooney Mara and her daughter, was the shot where she was walking down the street. Was that something that was in the script?

It was kind of in the script. We just said they walked home from church. The great thing with Rooney is that she is so wonderful with children and they instantly [got along], from the day they came in. They’d done a couple of auditions and they came to meet her. Just instantly they all just gravitated towards her and attached themselves to her and just wanted to be around her. So basically, whenever she is in a scene with them it’s more case not me directing but her just interacting. I was like “We’re just going to follow you for a while and just walk home and dialogue, talk about whatever.” That point in the movie the spirit is a little lighter. It was a good moment to capture the dynamic between the two of them and it really was that’s just how they were acting all day long.

You have two other projects here at Sundance, so how did your relationship with Shane Carruth start with Upstream Color?

We had a mutual friend and I was big fan of Primer way back when and I knew he lived in Dallas. We met officially last October as he was getting ready to make Upstream Color. Toby [Halbrooks], my producer, and I were like “whatever we can to help out we’re happy to do that,” and at the time Amy Seimetz was in post-production of her feature and I was editing it. So Shane was certainly aware, and he was an editor and he liked the way that film was coming together, I guess. At a certain point he asked if I would work on Upstream Color and I wasn’t sure if he was still shooting and I wasn’t sure if he just needed someone to do an assembly or whatever; but I wound up working on it now with him, all the way up until we started Ain’t Them Bodies Saints.

Did you come in to make an assembly or was there already one?

There was random scenes that were cut together. He had done a little bit and he had some other folks try things out but I think nothing was really working. I think because they were still shooting, he didn’t have the time to actually tackle it himself. I mean, he is an amazing editor and he has exactly what he wants; but he was shooting 12 hours a day for however many months they were shooting and it was too exhausting to put together, I think. I just kind of came in blind and started from scratch. So even the scenes he cut together I tried and did them over again. I didn’t look at his stuff, and more often than not I would cut them together exactly as he had because he is a very intentional filmmaker. He’s someone who when I would see the footage and there’s plenty of it (as you saw) there is a lot of cuts and every scene has multiple angles and you just look at it and go, “Ok, it’s a puzzle” and you just figure out how it’s supposed to go together and you get an understanding. [He would] tell me something like “the first act of the movie needs to be done under 25 minutes and she needs to have the worm taken out of her by that time” and my first was past that, almost an hour, because there was so much footage. He was like “No, no it needs to be under 25.” Then you’re just like, “Ok, if that’s the pace he wants, and here’s all the footage, then how do you make that work? Then you just gradually figure out the musicality of it all.

How long was that entire process?

Shockingly fast. I think I started on it in February. I started on it in LA while I was out there meeting the actors and I had a hard drive sent to me and we finished it in mid-May, something like that. And he certainly, after I was done, did some more work on it as well but when I watched it the other day I can’t tell. It’s all one big movie and I’m so proud to be involved with it.

Back to Ain’t Them Bodies Saints, I could definitely tell some certain influences, some as recent, when the three guys were all in the bar, as A History of Violence.

That’s funny that you mention that because I didn’t think about that at all, but that’s true.

There are little touches of No Country for Old Men, but I also know just in the filmmaking style it feels more like a Robert Altman feel or a Paul Thomas Anderson movie. Is any of that on the right track?

For sure, Altman and Paul Thomas Anderson are probably my two favorite American filmmakers. Someone else who I really love is James Gray; I really love his work. Then there’s other things, I spent a long time just being obsessed with the Pan-Asian cinema of the early aughts. I really just developed an appreciation for letting things linger and letting things be quiet and that still resonates, I think, on how I view things. Seeing those movies like, Ming-liang Tsai’s What Time is it There and Hsiao-hsien Hou’s Three Times was sort of like a revolutionary experience for me — Apichatpong Weerasethakul, I also love his stuff. I think it’s just so wonderful. Even though this film is completely different from that, I think that stuff still seeps in somehow and definitely had a huge influence on how I approach a scene. When I’m editing, removing dialogue, I’m like, “Ok, there’s still plenty of dialogue in the movie but there was originally more” and I love just letting silence speak for itself.

Did you actually shoot the scenes with more dialogue and then remove in the editing process?

Yeah, there were scenes that had…or sometimes in the script, there would be dialogue and we would be going through it and it’s like “You don’t need to be talking here, let’s just let this be quiet and then be silent.” Knowing that would work is always just really exciting, realizing you don’t need that is one of the best realizations you can have on set.

I loved Nate Parker and last year he had Arbitrage and Red Hook Summer here. Did you see any of his roles or any of his films before?

Yeah, I hadn’t seen Arbitrage yet, but I had just seen him in Red Hook Summer and Red Tails, both out the same week around Sundance last year. Especially in Red Hook Summer, I was just so taken; his performance was just electrifying in that. So his agent called and asked if I would be interested and I was like “Yeah, absolutely!” and we talked. I mean the second we first met, he got it — he got what we were trying to do; and he is just such an amazingly dedicated actor and so thorough. One of my favorite things is I got a peek at his process one day when I saw him on set, just by himself with a notebook. I saw the notes he had been taking. I didn’t read what they are, but I just saw how many there were and the handwriting he had written them in was so beautiful. I was always disappointed on set thinking,” Man, we need more scenes with you!” I wish that. I can’t wait to make another movie with him because he was so thrilling to work with. He’s such a wonderful human being.

I loved the environment his character was in. Is that something, in terms of location scouting, did you build that set or was it something you found?

That was one of the most specific sets we knew. We knew what it needed to look like and we definitely, it was like, the saloon in McCabe & Mrs. Miller. We looked at pictures of that and said “let’s make it look like that but not that old,” and it was the second to last set we found. It was actually an old grocery store in a hundred-year-old building, and it had a masonic lodge on the top floor and it was just gutted. We didn’t have to do much. I mean Jade [Healy], our production designer, added a lot to it, but the walls were all the same, we just left them the way they were and then she built the bar inside of that. That was one of those, we knew exactly what we wanted it to look like. Then once we had it built, Nate came in and just spent a lot of time getting to know and moving stuff around and so he owned that place by the time we started shooting.

How early on did you know that your film was going to be in Sundance Dramatic Competition?

We didn’t know. We found out the day before Thanksgiving and we just didn’t know if the movie would be ready in time. There was a point we were just like “I just don’t know.” We finished shooting at the end of August and it took a little while to just get in the rhythm of things with the edit. We called Sundance and just asked for an extension and then I asked for another. At a certain point I believed that we could finish it but I was like “if we show it to them I don’t know if they’ll actually think that it can be finished.” If someone else were showing this film I would be like “You got a lot of work to do.” I knew what needed to be done at that point; but they watched it and thankfully really responded to it. We certainly, had no idea if they would take to it or not. We just showed it. We sent it to them with a letter saying: “This is about to be a lot better, we’re just not quite there yet.” I feel like we were 60% there and luckily they really saw the potential of it and responded to what was there and then that was it. The next month, or three weeks, it all of a sudden just started clicking. There always comes a point with every film where it just really starts clicking and everything, all the decisions come really quickly and you just understand “Ok, this needs to happen here, this here, this here.” It just exponentially increases in quality and that’s the most exciting part, when all of a sudden everything just starts working. That happened in the last two weeks.

So you definitely don’t have the feeling, “Oh, I could’ve had one more week on it.”

I could have taken another week but I don’t know if the film would be that different. I think if I would have, I would say, “this shot might be a few frames longer” and “this shot would be cut in half”. I don’t know what it would be. When we locked the picture it was like six o’clock on a Friday and I was like “it feels like we’re done.” We keep messing with stuff but it reaches a point where it’s sort of arbitrary, the film is what it is and it’s good. I didn’t have the obsessive need to keep fussing with it. I think it’s in great shape. I watch it now, and I watched it at the premiere, and there are a couple little sound tweaks that I’m like “Oh, I can go fix those.” You know, make the volume better, switch out a sound effect, but those are the things only I would notice, hopefully. I don’t know, I mean if we had shot it at a different time frame and we had another month to edit or another two months or six months, I certainly would have used them; but I don’t think the final film would really be that different from what was seen or in some way.

In terms of your overall Sundance experience, have you been kind of consumed by this or able to check out other films?

I’ve seen one and a half films that I didn’t work on. One of them was Fruitvale, which I just loved. The other was Mother of George which was shot by our cinematographer. I had to leave halfway through to go to a meeting, an emergency meeting, so I’ll have to catch up with the rest of it. It was really good though.

Ain’t Them Bodies Saints premiered at the 2013 Sundance Film Festival and hits theaters on August 16th.