Dionysus in ‘69 is a nice title for a film that balances interests in intimate moments of human congress with the implications of such behavior on the social upheaval surrounding it. Its titular 69 goes both ways to the profane and the political — textbook Brian De Palma as many see him. But his documentary of a late-60s theater group adopts a non-didactic, wholly experimental manner, where pronounced cinematic ideas can find full flower to match the wild gesticulations and lawlessness that seem to be the ideal for the avant-garde group we see onscreen. The film is playful in this regard while still being held to many of the same basic formal requirements of a standard feature film. It has a runtime of 85 minutes, centering on a theatrical performance that at least has a beginning, middle, and end in the story of Pentheus, King of Thebes, and his duel with the Greek god Dionysus. But the performers are less concerned with the dramatic integrity of the story than the boundaries they can pass through with their orgiastic approach to a theatrical space. De Palma tries to use his unconventional techniques to dissolve similar boundaries between performer and camera.

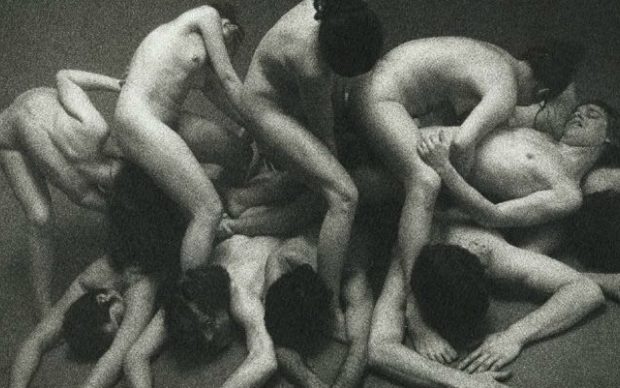

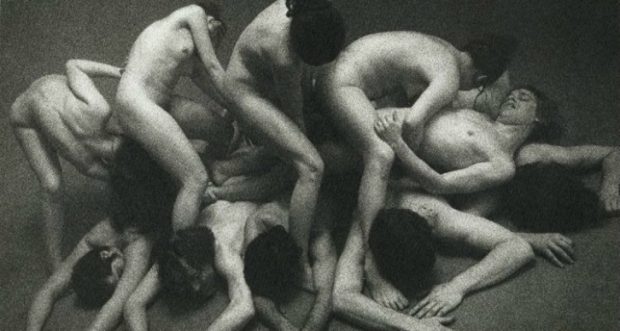

The battleground between Dionysus and Pentheus is in the plane of all human pleasure, the primary interest of the theater company putting on this play. The time and energy of performer and filmmaker alike is channeled into several set pieces of dramatized group canoodling. These scenes vary slightly over the course of the story; where some are loud and bestial, others have a rhythm and sense of jovial process to them that the performers and spectators seem to revel in discovering as the moment happens live. The end results of these scenes are multiple contorted human tableaus that, in the heap of bodies, convey different emotional charges. Each arrangement of performers and spectators shapes itself, and not simply as a blob. The arrangement of bodies in each becomes a living sculpture pursuing erotic emotions without reservation, evoking the visual modes of ancient Greece — which is at the skeleton of the play itself. The marble of these sculptures is a swaying, exposed limb in unbridled animal behavior.

The film has a visual palette consistent to a particular manner throughout. It is shot in constant split-screen, with one half of the screen occasionally black or depicting the same shot twice over. But, for the most part, each half of the frame, shot from two cameras on two operators at the same time, shows cross sections of the same action. In true De Palma fashion, the camera effects serve to make the viewer aware of the artifice of cinematic space. It has the added effect of being readable as De Palma’s treasuring of the camera’s tools for their own sake, another of the auteur’s stock characterizations. Where it might be an overhead shot or a particular kind of lens in a different De Palma moment, in Dionysus in ’69, the tool is the camera operator’s body, another player in this social erotic display.

If we take as more than apocrypha the story that Terrence Malick saw early De Palma films and thus shifted his focus to filmmaking, then certain moments from Dionysus in ’69 reach across time to find reference in Malick’s own works, particularly the later ones. As the first dance sequence transpires, the two cameras on either side of the split screen, with operators on foot, settle in to follow along with the rhythms that make up the core of this film’s meaning. The cameras push in on the action, and often walk from a wider shot directly into a performer’s personal space. In the second minute, the camera makes a sweep from behind his performer, turning over the shoulder to reframe the performer staring off into the distance. This J pattern is a common set-up in later films by Malick, the floating camera often pushing in to its characters to assign your perspective with theirs and reveal their ways of seeing in a flurry of loosely associated moments. De Palma’s use of this move works on an entirely physical level, delighting in the camera’s (and the camera operator’s) capacity to mimic the actors’ bodily presence. It works instead to assign your body to the scene, just as the performers and many spectators at the performance within Dionysus do.

A recurring game at hand in the staging is a denial of authority, often literally the denial of the authorial conceits of character and dramatic irony. The play finds drama in the clash of powers and denial of agency, which this theater company chooses to evoke in a lack of respect for a scene’s integrity. Dionysus tells Pentheus that “you are not Pentheus, king of Thebes” before calling that same actor Billy moments later. As Dinoysus struggles with the fact that his position as the God of pleasure leads man to regard him as more vulgar than other gods, the actor acknowledges that this regard is shared by the crowd watching the play. He is “Dionysus, not recognized as a true god by everyone in this garage.” This churlish behavior frustrates any attempt at stately seriousness with which one might regard the drama. In the closing sequence, the Dionysus character admonishes Pentheus, and, much in the way a Greek god would administer punishment, Dionysus instructs Pentheus’s actor, Billy, that he “will have to do the same thing tomorrow night.” This trope demonstrates that the style of the play stands as a rebuke to all of the day’s established authority, particularly as the play and film conclude with Dionysus’s campaign for President of the United States.

Dionysus in ’69, like any good self-announced time capsule, has all the hallmarks of its age with tendrils reaching out into the present. It bears connection to the recent, dance-inspired experiments of Terrence Malick, but also to the newly-restored Out 1, to which it more explicitly compares given that both focus on narratively oblique but propulsive goings-on of avant-garde theater companies. Both give images to what is in part the legacy of how the late ’60s felt: flights of fancy shakily built on the ethereal foundation of play and youthful trial-and-error, the hallmarks of a new generation’s social contract. Both use experimental theater adaptations of classic works as a metonym for their own method of creation, where the roving and reaching-out of the performers to one another represents the cameras’ attempts to collapse distance, both between camera and performer and between two cameras on the same frame. The ritualistic aspects of this theater company’s artfully wild performances mirror a clash between the rules of the establishment and the governing impulse towards free expression of the younger, more artistic generation.

Continue reading our career-spanning retrospective, The Summer of De Palma, below.