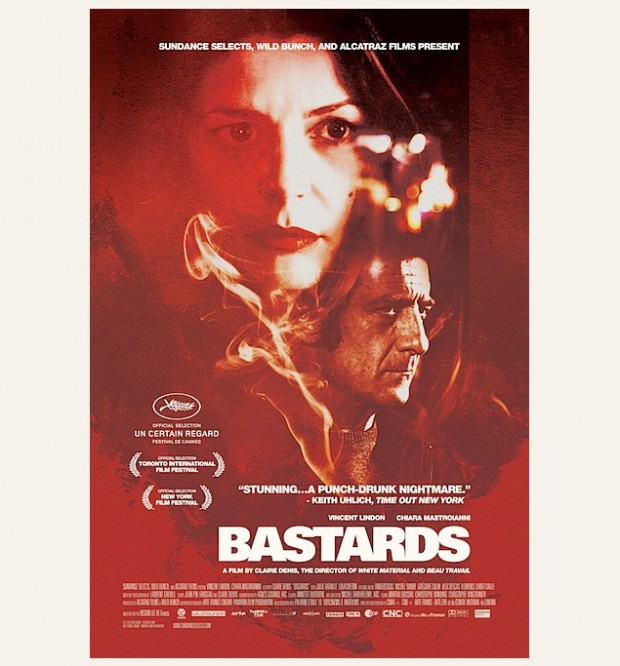

Some four years after White Material, the inimitable Claire Denis has reentered our sights with Bastards — a picture which, though very clearly the result of her particular skills and interests as a filmmaker, is nevertheless something of a shock once seen with one’s own eyes. Less than an hour after its brutal, uncompromised final images played at the New York Film Festival, I, still processing what really transpired, had the opportunity to speak with her, and our twenty-minute discussion is what follows.

While sitting down and activating the recorder on my phone, I told Denis, with full earnestness, that it was an honor to have her time — prompting what is easily the best start to any interview I’ve ever conducted:

Claire Denis: I don’t wish to open with a refusal of your introduction, but… I consider the word “honor” a little bit too much. It’s nice to hear from you that you like my film — and it’s nice to try my best to answer your questions — but “honor,” for me, it’s such a military word. I would prefer “pleasure,” or…

The Film Stage: Well, it is also a pleasure.

Okay!

[For the next ten seconds, I stumble through a hasty joke attempting to tie the mention of military and her 1999 film, Beau Travail. Denis politely smiles.]

The film has been “available,” in some sense, for a while now, having premiered months ago at Cannes and getting a few stopovers between now and then. I wanted to ask, first off — I’ve just seen the film, myself, and am still processing it; reeling from it a bit, too — what have you made of the reception to Bastards thus far?

It’s… other people, they like it, and for very different reasons, but they understand something in the film that they like. Some people completely dislike the film — and, I must say, mostly for a reason I tried to capture, but I’m not sure I understand. It’s something that… I don’t mean that I expect all my films to be appreciated completely, but it’s just… to be suspected of doing something “taboo,” or out of morality, or whatever, is weird. Because, number one, I don’t care so much about morality; and taboo is not in the filmmaking. The taboo is what happened between a daughter and her father, maybe. But taboo is something… if the word exists, it’s because it can happen.

I tried to understand, in Cannes, the critics — the ones who completely disliked the film. Even people who kept telling, “We like her so much when she does White Material, but suddenly, my God…” But it’s difficult to understand not being disliked, but why. I would like to learn why; I would like to understand. Is it the image at the end? If this is the image at the end, I don’t understand. Is it the subject? We had a debate in the Cahiers du Cinéma, and it was nice, because… we were not even speaking about the film. We were speaking about “why did I make a film like that?” And it was interesting for me, too.

But I was trying to grab information: Why? Why? What did I make wrong? But I didn’t know.

The way reaction is noted, I glean that you, while making a film, go through some process of figuring out your own work and why you’d take certain directions. When in development — from the first stages of screenwriting up to the last edit — do you have a moment where everything dawns on you? That’s how I felt watching the movie; there was a certain point where it all cohered for me and where it became a full vision.

No. There is a part of that, at the end of the scriptwriting — I have a sort of vision at that moment. But, in the process of shooting, it’s more difficult, because I tried to keep in mind the totality of the film — but, of course, it’s a day-by-day process with drawbacks, and whatever. It’s only in editing, at the end of editing, that it clicks again, and I think, even though the editing… it’s always a rush. So I think, when mixing the film, that I am in the auditorium, mixing the sound and the music, and watching the film, that there is a full… I see the film for the first time, then.

For myself, the actors you often collaborate with provide a connecting thread, and after so many similar roles, associations begin to form. The tender masculinity of Marco [Bastards’ lead] brought to mind Vincent Lindon’s character in Friday Night, while the quietness of Alex Descas couldn’t help but raise 35 Shots of Rum. Is there a balance when working with new and old performers — when, on set, there are both actors who’ve never been with you before and those who might be making their sixth collaboration? Or do they work in the same way for you?

No. Vincent Lindon is a very anxious actor, and he trusts the director — he trusts me — so he is not asking for a lot of explanation, but he needs… love. He needs attention, because his anxiety is really big. Alex Descas is, also, a very anxious actor, but it doesn’t show; he’s like a blank, so I have to understand what is… “maybe this is not good for him,” but you would never say. Chiara [Mastroianni], I’ve known her for a long time, but it was the first time working with her. She had a completely different reason from the others: she never asks for time, she’s ready to jump, and she’s very generous, never showing doubt. She trusts. It’s great to work with her. Lola, the little Lola Créton, the same; completely trustful. Michel Subor, it’s different: it’s like a guy smoking a cigarette. I enjoy that moment. After, I think, he will complain about this and that, but when it’s time to shoot for him, he enjoyed that moment very much.

I was rather excited upon hearing Lola Créton would be in the film, as she’s become, I think, a young face of modern French cinema, having worked with Mia Hansen-Løve and Olivier Assayas. Could you talk about deciding to go with her?

I was… she was… I did not decide for her at all. Because I like her so much, I was afraid to ask her, and I knew someone who had said yes — and who was, maybe, in my opinion, stronger to resist — but, then, in the end, I thought, “I’m wrong. Lola is going to be better, and if she accepts — if she trusts me — it’s going to be better with her.” But I was afraid to ask her.

Did you speak with any of those directors about her?

No, because I think everyone’s experience you can read in the film. If I ask, to Mia, what she felt… it’s important, when I saw Mia’s film or Olivier’s film, I saw things that I understood immediately. So to ask the director would be offending for me — as if the actress, itself, is not the one who is doing their job.

This is also your first feature shot digitally, and seeing it with that in mind provided a unique experience. It still “felt” like one of your movies — you could still detect the texture of the images — but there was something smoother to it, which perhaps comes from the technology.

Yeah.

Was there anything that needed to be changed? Something which was conceptualized but, when you actually began filming, you realized the digital had too strongly altered?

Of course. I wanted the film to be dark, to be nocturnal, and with the RED Epic, this darkness is not an easy thing, because it’s a camera that sees everything. So, to balance and create this feeling of darkness, the process of lighting was very difficult. Of course, if I used the RED Epic in this room, with no light like that [gestures around the room], you would see everything, even the grain of my skin.

But, me, it’s the opposite: I wanted the apartment to look like a tomb; I wanted the forest to be deep and dark. So, it meant to go back to a very artificial light. Not to use it as digital — of course, with digital, you don’t need so much light, unless you want this mysterious obscurity — but digital softened, in a way, some lines, and… it softened the lines and increased the contrast. It’s very strange.

Now that you’ve had something of a learning process on it — and, having seen the film projected digitally, on a big screen, it looked rather nice; it felt as if it was “yours” — do you see yourself sticking to it exclusively from this point forward?

I don’t know. I will see. I think, for me, what is interesting is to have the choice. I think it’s terrible to decide, “Because you invent a car, nobody is allowed to go on a bicycle.” You know what I mean? For me, right now, I’m happy labs are still developing film. But of course I will work on digital, yeah, but why not — for a certain project — work on film? I will do it, yes. I saw the film The Master. I was in a theater, in Paris, and when I saw the 70mm film, I felt a sort of emotion that I thought I would never feel anymore. This texture of the 70mm film blocked my… I couldn’t breathe, you know? I was, like, [throws hands in air]. And I think it’s great to be able to see that today, you know? I think Anderson was right.

After the film, a friend of mine remarked that, while most of your work has a certain softness and sensuality to its character, Bastards would be the intense, rigorous, and hard inverse to that. How did you go about finding this sense in the story?

It’s the story itself. Every love moment is almost a rape — except the staircase, but it’s in a staircase, so it’s not in a bed, you know? So I think it’s a matter of the film. To quote William Faulkner — because I think he is very important for me, and he is in that film — it’s not a “love scene”; it’s fornication. And fornication means… even the sound of the word “fornication” means not the same thing.

You have something such as the staircase, with its rough associations, and you’ve commented that the apartment feels like a tomb. The spaces are, clearly, so elemental to the feeling you wish to evoke, so how do you go about in finding a location? When you find a location, how might it speak to you as what was initially pictured?

[Pause] It has to correspond to the script, even though I describe space and places in the script that does not exist — except when I know those places before. But, no, I figured I was looking for this kind of building style, and when I find two, I choose the one that, in the end, represents… something like fear, and a place I certainly could not live in.

In the film’s press notes, you say that using digital feels like the beginning of a new phase. Do you see Bastards as an especially important next step in your career?

Number one, I have to tell you I have absolutely no, and it’s very honest what I say… the notion of “career” is a very hard thing for me, because I have so little vision of my life that to have a career means… I would see a sort of line. Career? No. And if this film is going to mark something in my life, it has already. Like any film, it’s sort of a scar, you know? It’s there. It will never be the same after, you know? It’s not a… it’s not like, in banking, or for, like, a capital. You don’t get more land, more factories, more houses; in filmmaking, maybe it’s “one more film.” But it’s less of me. Something is gone, you know?

After being done with a film, as is currently the case, do you require a period of relaxation and contemplation?

Oh, no. No, I work. I don’t need relaxation. I’m not cool. I hate relaxation. I like to work, and the best way to soothe the mark of the last film is to project myself in another one.

Bastards is currently playing at the New York Film Festival, and will be released in theaters, courtesy of Sundance Selects, on October 23rd.