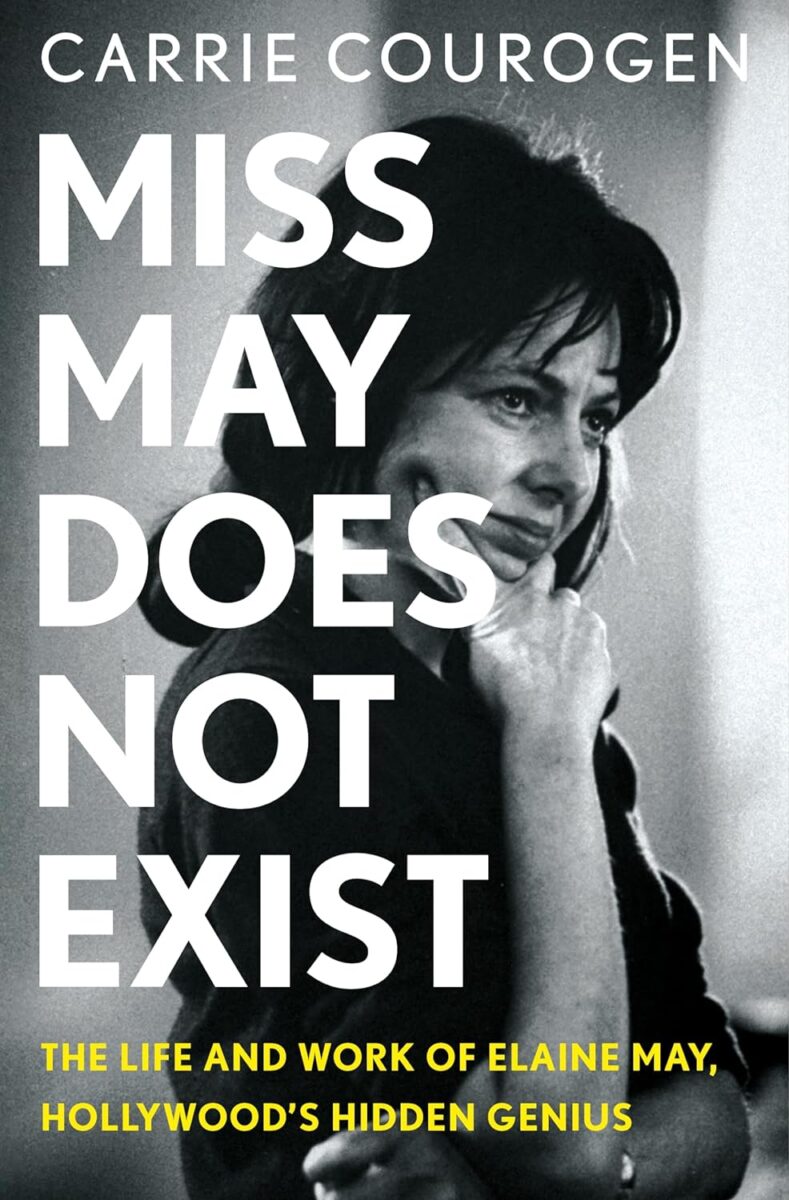

Before now there has never been a full-length biography of Elaine May, the icon known for being one-half of Nichols and May and the director of A New Leaf, The Heartbreak Kid, Mikey and Nicky, and the hilarious, unfairly maligned Ishtar. Miss May Does Not Exist: The Life and Work of Elaine May, Hollywood’s Hidden Genius is the book that fans of May have been wanting for, well, the entire career of the comedian, screenwriter, playwright, and filmmaker.

The world, it seems, was waiting for Carrie Courogen. The writer, whose work has appeared in Vanity Fair, Teen Vogue, Glamour, and Pitchfork, pored through archives, conducted interviews, and dug deep to highlight a person who has avoided the spotlight for decades. Miss May Does Not Exist obviously enhances one’s knowledge of May, but it also succeeds in something far greater: it deepens our cultural appreciation for a figure whose work has been ludicrously underseen and undervalued. While we are unlikely to ever hear May’s thoughts on the book, anyone who reads the biography will surely come to the same conclusion: Courogen writes with the wit, intellect, and insight her subject deserves. Miss May Does Not Exist is brilliant, indispensable, and utterly extraordinary.

As the book arrives on shelves this week, Courogen discusses the monumental task of covering the life and work of Elaine May, comments on May’s resonance to younger audiences, and explains why May is but one example of the many women of her era denied the opportunities afforded their male peers.

The Film Stage: Let’s start with your connection to Elaine May. What are your memories of discovering May and her work?

Carrie Courogen: There was a span of 20 years between the first time I discovered her and then the first time I connected with something that she did. I first discovered Elaine May when I was probably 12 or 13 and first falling in love with comedy. I saw Saturday Night Live and I had this obsessive “I love this and now I have to learn everything about this” sort of spiral down the black hole. And I remember, in my need to educate myself on the history of comedy, I went to the library and I got a copy of Nichols and May At Work. A lot of it went over my head, obviously, but I was fascinated by the dynamic between them. And it was the era of SNL when Tina Fey and Jimmy Fallon were on Weekend Update. So I had this sort of parallel when I listened to Nichols and May where I just immediately thought, “Oh, that’s what Tina and Jimmy are doing. They’re just doing Nichols and May, like these are the OGs.”

And I loved film, and loved classic movies. I was a big tape-shit-off-TCM girlie. I loved Mike Nichols’ work, but I kind of just forgot about Nichols and May for a long time. And I never knew at the time that Elaine made movies. And I think it’s probably because, for a very long time, her work was under-discussed. It was very hard to find. A lot of it was still out-of-print. There wasn’t such a focus in the early aughts on female filmmakers and Hollywood history of mistreatment. So I really went about my life being like, “Yeah, I love Mike Nichols’ movies. He’s great. Oh, yeah, he had that comedy act with Elaine May.” I don’t know why I never got curious enough to see whatever happened to her. Until 2018, when she was on Broadway in The Waverly Gallery, and suddenly her name was everywhere. It was like an old friend that I hadn’t seen for a really long time. “Oh, my God! That’s her.” And I remember reading a couple of early pieces that mentioned “now that we’re talking about her because of The Waverly Gallery, it’s time we talk about her movies.”

Immediately, the same 13-year-old obsessive, I-have-to-know-everything-about-this brain kicked in, and I just went down the wormhole, and I read her plays and I watched her films, and I think within maybe 30 minutes of seeing A New Leaf for the first time I was like, “I love this. I think this is so much fun. And I think it’s criminal that a movie like this isn’t more well-known.” I remember also kind of scolding myself because I had at that time kind of developed an interest in writing what I call revisionist history, where we’re looking back at great canons and saying, “Here are the women that we forgot about or misremembered or overlooked or have gotten bad raps.” And I was kind of like, “Here’s a prime example of that. Why have I not touched upon this sooner?”

How did you move from “this person is amazing” to “this person is amazing and I’m going to write about her”?

Late spring, early summer of 2019, before the Tonys, I started working on a profile of her for Glamour and at the same time also working on an essay about her plays for Bright Wall/Dark Room. I did a lot of reporting for the Glamour piece and it ended up being much, much shorter than the draft. It went through a bunch of different iterations, but I remember during that reporting thinking, again, “I love Mike, but it’s fucked-up that there are, like, three books about Mike and all these great books about Hollywood history and the era of New Hollywood where Elaine is really a footnote, or she gets to be the supporting character in all of these stories.” But at the same time, knowing there’s a reason why there’s not a book, and in my mind thinking, “I really want to write this book but I don’t know how to do it because she’s not going to give me access.” There’s a reason why if it hasn’t been done by now––it’s got to be impossible. I kept trying to think about how I could do it and how I could get around the access issues. And also thinking, “I want to write a book that isn’t encyclopedic. I want to write a biography or a nonfiction book that has life to it.”

I was sort of working through that the rest of the year into 2020. April 2020––the height of sitting at home, not doing anything––a couple of agents started to reach out to me about writing a book. I really connected with my agent who I have now; she’s wonderful. I remember I said to her, “I have a couple of half-baked ideas. But the one that I really want to do just feels so crazy and impossible; there are all these roadblocks to it. I don’t think I’m the person to do it, but I really want to do it because I had this sort of presumptuous sort of feeling of, if I don’t write this book, some stuffy white guy is going to write this book, and I’m going to be so pissed that I didn’t.” [My agent] was like, “Just go for it. Write a proposal and see from there.” I spent the rest of summer 2020 doing that. And slowly but surely it started to take form. Getting to the point of “I want to write this book and I am going to write this book” was a very long, slow process of talking myself into it.

It seems like people a couple of generations younger than Elaine May have really embraced her work. Why do you think that is?

That’s a really good question. I think part of it is just, like, she’s so undeniably funny and sharp and mean. We live in such a Ted Lasso world where people are so inundated with feel-good comedy that people––at least older millennials, I would say, or even Gen Z a little bit––they want sharp comedy again. They want to hear things that are witty and slightly cruel, but not punching down––just cruel because they’re honest and not so delicate about it. There’s so much conversation right now about how you can’t say anything in comedy anymore. Yes, you can actually. And here’s somebody who did say a lot, and her work for the most part holds up and is not inoffensive. I think that’s one reason, and I think another is that we have a lot of respect for people who are so unabashedly themselves, and so gonzo, “Fuck corporate America, fuck the corporate studio system, I’m doing things my way, I don’t care.” There’s something very punk and very independent about her that I think resonates with younger people.

In Miss May Does Not Exist you point out that pretty much every film she directed––The Heartbreak Kid, Mikey and Nicky, Ishtar––was ahead of its time. If she had been able to continue directing, what direction do you think she would have gone in?

It’s interesting, because I think, at the end of the day, she was a director mostly because it was a form of quality-control rather than having something specific visually that she wanted to communicate. It’s more like she had a script and she wanted to make sure the final version was as true to what she had on the page as possible. So I think she probably would have gone in the direction that her plays went in, almost always very focused on the same sort of themes of betrayal and relationships between two people. Mostly men and women. But they probably would have been smaller. I think Ishtar was a fun experiment. It was like a let’s-see-if-we-can-do-it-to-do-it sort of thing. I think she probably would have gone back to the realm of more independently shot films and smaller productions, more like Mikey and Nicky, more like The Heartbreak Kid.

In the prologue you refer to the difficulty in loving Elaine May––knowing that she could have had a more prolific career. Ultimately, when you look at her career, do you come away feeling positively or negatively?

I’ve come away from it, unfortunately, feeling more sad for her, but also frustrated by her because I don’t think it’s entirely Hollywood’s fault that she hasn’t done more. I think she absolutely has a hand in her fate, and I think that she is surrounded by a circle of protectors and colleagues that she only wants to work with, and they all sort of act as yes men to her––to her detriment. And I think that it’s very sad to see that she’s limited in this way, because I think a lot of times if she were more open––or if she had other viewpoints in her circle telling her to do something different or not encouraging her incredible paranoia and distrust of everybody––I just think that things could have been much different. But again, that’s who she is. And that’s what makes her work great––that she is paranoid and distrustful––and it shows up in all of her work.

You note that Elaine did agree to answer four questions in writing before withdrawing that offer. Now that the book is finished, how do you feel about that?

I am a touch disappointed, mostly because I had four questions that I narrowed it down to that would have helped explain a couple of little plot holes that I found. I could ask her a million questions. But if I only get four, these are the four that are most important to me. At the same time, she’s going to give me an answer that is a bit. She’s not going to be truthful with me; she’s not going to sit down and be vulnerable. She’s not going to submit to the mortifying ordeal of being known; she’s just never going to do that. And of course part of me also feels really sad for her that she doesn’t feel she can do that. Because she has a life that deserves to be known by other people. And she deserves to have a say in her own story. That was very important to me.

Unfortunately, I don’t think she wanted to have a say in her own story. I think my disappointment is more that, at the end of the day, I just wanted to meet her to say, “I’m not out to get you. This is not a hagiography––I love you, and this is a love letter to you. And yes, it’s honest, but it’s not an attack. I just want you to know that I want to do right by you.” I really just wanted her to know that and to feel that she could trust me. But I also completely understand that there are a lot of circumstances and a lot of contributing factors to why she doesn’t think she can trust me. There were certain occasions where people were like, “If you could just get her on her own, she would be completely sweet. But there are these people who surround her who are like gatekeepers. That makes it tough to prove yourself when you don’t have a direct avenue to be like, ‘Hello, how are you? I am a normal person.’”

Honestly, I think the book probably would not have been as good. It would have been funny, maybe, to have that brief Q-and-A––like, this is how controlling she is. Obviously it says a lot about her more than some things that I could write.

What’s your personal favorite Elaine May project? And for you, finally, what does she represent to you?

I am in Ishtar-head. I think my intellectual, highbrow answer would be The Heartbreak Kid. But at the end of the day, Ishtar is the one I rewatch the most.

As much as the book is about Elaine, I really came away from it thinking she’s not all that unique. There are so many more women who worked in Hollywood at that time who didn’t get the chances she had because they weren’t as lucky or who got some of the chances, but suffered the same fates as Elaine but weren’t as well known. She’s kind of a poster child for a catch-all women-in-Hollywood sort of ordeal. I think I came away from it thinking it’s not an accident that she doesn’t have a prolific body of work. It’s not an accident that so many women directors don’t have prolific bodies of work. They don’t have, you know, vast filmographies like some of their counterparts and peers, especially from that time period. It struck me that there was such a pattern of, like, one-and-done or two-and-done, or do a couple of and then move to TV because it’s cheaper and you can get a budget. And I think that was sort of what I came away from it thinking––Elaine was incredible, and a trailblazer, but she’s not the only one.

Miss May Does Not Exist: The Life and Work of Elaine May, Hollywood’s Hidden Genius arrives on June 4.