While you may know him as Bill S. Preston, ESQ, Alex Winter the actor has effortlessly become Alex Winter the director. Hot on the heels of his successful Napster documentary Downloaded comes Deep Web: a look behind the curtain at the 96% of the internet we don’t see. But while the film began as an overview of this expansive world freely accessible by Tor—for good (journalistic anonymity) and bad (illegal drug trade)—something happened during production that blew the doors wide open.

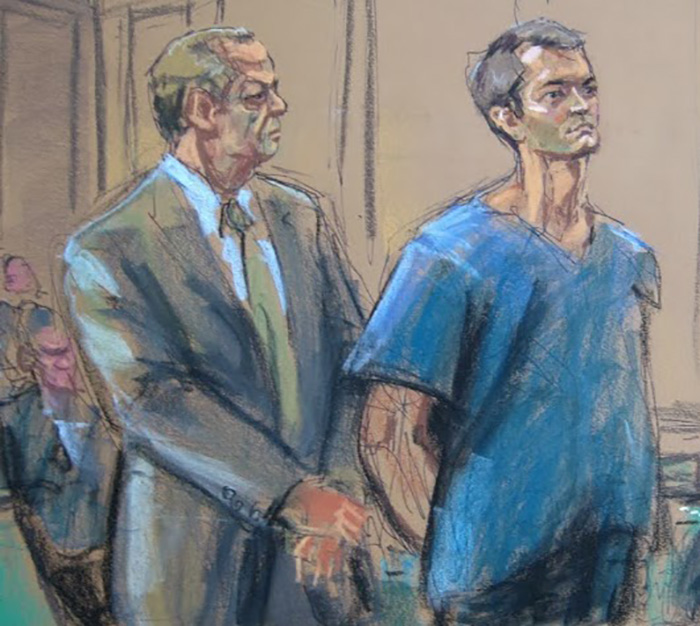

Ross Ulbricht was arrested under the accusation that he was “Dread Pirate Roberts”, leader of black market site The Silk Road. It was his story that Winter eventually focused upon because the ensuing case shed light on the government hacking its citizens’ digital footprint as well as the fight against it.

With exclusive access to the Ulbricht family as well as interviews showcasing former Silk Road merchants and cryptoanarchists active today and ever vigilant, Deep Web looks to open the public’s eyes to a reality of which most are wholly unaware.

The Film Stage: I reviewed Downloaded back in June 2013 and during that process discovered you were already talking about Deep Web as your next film. I’m curious to hear about the evolution from that initial idea to what it became in the aftermath of Ross Ulbricht’s arrest October of that same year.

Alex Winter: I was looking at it as a continuation of the same conversation we started with Downloaded. How these online communities were growing from the birth of the internet and then sort of exploded with the ease of use from Napster. Suddenly the Average Joe was connecting online by the hundred million. That was a very new thing and it gave way to a lot of stuff. To me it was a natural line of progression, as I think it is for a lot of people, from Napster through to WikiLeaks, the Arab Spring, Chelsea Manning, Ed Snowden, and The Silk Road. And that started from long before Napster with the work of the cypherpunks back in the 80s and 90s.

So it was really a kind of continuation of one conversation about how there’s this movement towards a free reign online community. They aren’t just about contraband, Libertarianism, political views, or even always anonymity. This story is sort of focused more on the privacy and anonymity movement that grew up on the internet and, really, Silk Road—just like Napster—was a catalyst for the ease of use of being in an anonymous community that’s scaled.

I think it was the simplicity and the brilliance of the way that Tor and BitCoin were combined. It was inevitable but someone went ahead and did it and it took off. Silk Road really put BitCoin on the map and really illuminated [things] for a lot of people who didn’t know there were anonymous communities that have always been on the internet. Suddenly it became a lot more widely known and more importantly a lot more widely used.

That was kind of the impetus and once Ross got arrested in October I sort of found my human way into the story by following his travails. I knew I wanted to make a limited story—meaning not just hanging onto this thing for the next two years because it’s certainly going to go all over the place. It really just localized my story to say, “Okay, I’m going to talk about how we got here, what’s happening to this guy, what happened in his trial, and what may happen from here.” And just leave it at that. That was kind of the aim.

In the film, Andy Greenberg from Wired becomes this crucial objective voice keeping things from going wholly into an anti-government, David and Goliath tale that the cryptoanarchists you interview are pushing towards. Where did his involvement begin? As a subject, a producer, or always as both?

The way it started was that I loved Andy’s book [This Machine Kills Secrets: How WikiLeakers, Cypherpunks, and Hacktivists Aim to Free the World’s Information]. I felt I had found this kindred spirit who also saw very specific threads flowing through a lot of the movements that had occurred since the 80s. And even before, but strongly in the 80s. With Napster I sometimes felt I was piling into a canyon—the purpose of that film was very narrow. I was only interested in looking at Napster as an online global community. That was the motive from my perspective. It wasn’t to either exonerate it or to denigrate it. It was simply to focus on it from that perspective.

I knew that with Silk Road I similarly only wanted to focus on this narrow perspective. But coming out of Napster—it’s hard to tell stories like this that don’t just toe the party line and fall in line with the prevailing narrative. Making a Napster movie that wasn’t about stealing music: it was more provocative than I realized going in. So with this story I was definitely looking for other voices besides my own that echoed my perspective. I really found that with Andy.

So what I wanted to do with this movie was have—I don’t think Andy even realized I intended to do this. I wasn’t duplicitous. You just don’t really vocalize subconscious ideas when you’re blocking a doc together. I knew I kind of wanted Andy to be “The Guy” for the audience. So I don’t think he quite realized the degree to which he’d be in the film. It was all good and friendly, but I don’t think he realized he was actually the protagonist of the movie from my perspective.

I certainly did reach out and option the book. Our team optioned the book and he knew he was going to be consulting on the movie and doing a couple of interviews.

What was it like to kind of create this film while its content was literally unfolding? Not just with Ulbricht’s trial and unearthing those details, but also more human aspects like Ross’ mother Lyn becoming a digital privacy rights advocate?

It was a really unintended facet of the story that deservedly grew to the forefront. I expected Ross’ mother to be supportive of her son. That’s pretty standard. I did not expect someone who—like my mother—is a total luddite, through this process, to become as versed in the digital rights issues at play [as she did].

You can cynically say, “Well, she’s going to do whatever it takes.” That’s all well and good, but a lot of my friends who are tech-based can’t explain cryptography as well as Lyn can. I think that she sort of blossomed into this other person. I think she surprised herself and I think that was a pretty extraordinary thing to witness firsthand. I kind of saw it happen and it was pretty extraordinary to witness. It’s sad. I don’t think it’s some inspiring tale. It’s an incredibly tragic story and I think this movie is pretty damn grim, but it was extraordinary to watch both she and Kirk really become radicalized. Intelligently and articulately radicalized.

To me there’s a thematic point there because I think a lot of people in this day and age are becoming radicalized by what they perceive around them to be very thorny issues—many of which are not being discussed adequately or properly or being criminalized or fought against. This is separate from Ross and The Silk Road, just to be clear. I think that became almost emblematic of the larger issue at play and I certainly wasn’t cynical enough to look at Lyn and Kirk and think they’re only getting radicalized because of their son. It went beyond that. They were sort of awakened by the circumstances they were thrown into.

Lyn makes no bones about the fact she’s—she’ll probably even contest what I’m saying and go, “Look, all I care about is Ross.” She would be very modest about this whole thing. She doesn’t view herself as an activist. She views herself as a mother who is very eager to try and claw some life back for her child. But the truth from an outsider’s perspective that was on the inside like myself, it just goes a lot deeper than that. And that became a human way into the story that I wanted to tell.

You’ve embraced the digital realm by building communities around your work through social media and the like. And while your documentaries are compelling stories on their own, they’re also pieces of a larger whole looking beyond the “evil” surface of the internet that the media loves to showcase. What are your goals as a filmmaker and as a recognizable artist with that social media reach to continue this conversation?

It’s not really about the technology—I don’t really care about technology or the internet. I just found myself at this moment in history where all these extraordinary things are going on. And I felt that way when I first encountered the internet back in 1983-84. It was just evident that it was going to change everything in ways that people couldn’t even imagine.

I find that really fascinating from a human side, but the thing I have always been most interested in is this notion of the democratization of culture. I was giving this example earlier: to me the Iranian nuclear arms deals are a really good case and point where you have a lot of propaganda on both sides. Sort of vociferously arguing for and against this deal from within each community—the Iranian community and the western community. And yet, because of the internet and because of global community, you have this capability to sit above that fracas, co-joined with these people. You can really separate yourself from the pluralism and the propaganda and the duality to be one with this community.

Again, it’s not to say that you had a hard and fast opinion one way or the other—it just was. This ability to rise above and outside prevailing narratives. It’s the first time as a culture that we’ve really been able to do that en masse. We’ve always done that in groups, right? We’ve never done that en masse.

So I’m really interested in community. To me Kickstarter or Indiegogo or webpages or Twitter accounts are just a way to jack into that community. Twitter may go away and be replaced by something else. The community will live. Napster exploded and that community stuck together and moved on. The Silk Road was shut down but that community stuck together and moved on.

With Downloaded, we didn’t Kickstart it but we created this online community—some of who were liking my Facebook page with that sort of hard and fast connection and some of whom weren’t that specific. We just kind of all knew each other because we were all in the ether together.

With Deep Web we wanted a more specific community so we specifically created a Kickstarter campaign. We didn’t ask for a lot of money because we just wanted to build a community and take it with us through the movie. And of course it had an additional benefit in that it smoked out most of the major deep web players who—I had a PGP key, they contacted me through that key, and I was able to actually meet most these people. Or at least learn about them and verify them through other means. But a lot of them I was able to contact and we planted that flag in the sand through Kickstarter. There are so many different ways of being present in these communities and that is something I do really connect with whether I’m telling a story about technology space or not.

Where Napster and its aftermath found the music industry finally adapting to its audiences’ desires, the cryptoanarchists in Deep Web are taking things further by disrupting the government directly to the point where Ulbricht has become a trophy for one side and a martyr for the other. Do you see an aftermath or will the fight simply keep evolving?

I think that Bruce Schneier put it best and Andy [Greenberg] quotes him in the movie. “It’s a game of cat and mouse. In the end the mice will win, but the cats will be well fed.”

I think that really sums up the hard and fast reality, that the median curve of these movements has done nothing but grow exponentially up. And from the beginning of the internet’s existence you can chart Napster as a huge explosion in the amount of people that were convening online outside institutional control. Then WikiLeaks and then BitCoin and then Silk Road and then the proliferation of markets and then decentralized markets and then mesh technology. It’s exploding exponentially.

Is there going to be continued institutional pressure against this movement? Absolutely. Are there—this feels so obvious, I hate even saying it. Are there bad things that happen in this space? Sure. Just like bad things that happen in whatever city you happen to live in. But the expansion of these movements is increasing.

A lot of people are interested in the potential of making the Bill & Ted franchise into a trilogy. Any plans on pushing forward with these community ideas to see that happen?

We’re working on a third one—it’s no secret. Whether we crowdfund some part of that is up for grabs as we’re into it with other players right now who have a say. So everyone has to agree.

I would love to see a crowdfund for Bill & Ted 3. I would love it. I think part of the reason we’ve gotten this far is because the community has been so behind it. There’s no doubt. We’ve been buoyed along by the community—there’s nothing premeditated about it. In a way it was sort of beyond us. We were like, “Oh. Holy shit. There’s all these people who really want to see this film.” [laughter]

I would love to be able to bring them into this thing in a more direct way through some sort of crowdsourcing strategy and campaign. It will probably be less monetary in a way—sort of like what we did with Deep Web where we didn’t rely on it for the whole budget. So that would be an interesting possibility that I would love to see happen personally.

And with the success of Super Troopers 2—something that kind of fits that mold—there’s definitely an audience to help make that happen.

Agreed. There have been many. I think we’d do quite well there.

Deep Web is currently on the festival circuit. It debuts on Epix on May 31st.