A renowned filmmaker in French cinema for her social realism across many storytelling modes, Claire Simon has crafted documentaries (such as depicting the admissions process for a prestige film school in 2016’s The Competition) and lesser-known largely scripted narratives (such as 2008’s God’s Offices and 2021’s I Want to Talk About Duras). Her films imbue a profound understanding of how systems confined people across all levels of its pecking order and how they don’t let it obstruct their journey.

Her most recent, nearly three-hour-long documentary, Our Body, captures Simon, and female, and transgender and gender non-conforming (TGNC) patients seeking medical care at Paris’ Hôpital Tenon. While it can be scary for them to go to a doctor due to systemic discrimination, Simon delivers a visceral, emphatic portrait of patients undergoing cathartic surgeries and cooperating with surgeons for a more admirable future that is beneficial for their health.

Ahead of the film’s theatrical release, I spoke with the director about the inclusion of herself in the film, critics’ frequent comparisons of Simon’s work with Frederick Wiseman, and how Simon doesn’t see Our Body being part of 2020s hospital nonfiction cinema.

The Film Stage: In Our Body, many patients have a fluidity of options for their concerns. What led you to pick Hôpital Tenon instead of other hospitals nearby?

Well, it was because my producer [Kristina Larsen], as I said in the beginning of the film, stayed there to be looked after because she had a special disease. She went there for two years and she knew the doctors. When she talked to me about her experience, the unit was really strong, because it was all about gynecology, from youth to old age for all kinds of things. Good things and bad things like having babies or being young contraception, abortion, gender transition, cancer, and all these things. I always thought it was extraordinary, this hospital would have only [one] unit for women. I did a film a long time ago called God’s Offices. It was fiction, based on the documentary research about family planning.

When I presented it in a town [hall] in France, the whole hospital came. And they did the same. It was in two, and they had the unit for all the gynecology for women. I thought it was wonderful because instead of cutting the woman’s body and slices, it brings it back to only one thing, which is the stages and the steps of life of a woman. Anywhere of someone who has a neutrois breast. What I thought was a really great thing to know was that the gender transition was included in this unit. I thought it was really very interesting. Not all the hospitals have this unit of all the gynecology together. Why not, I would say the contrary.

Unfortunately, sometimes I regret I’m not a journalist, but I am. Also, I always take the risk of the place and the people I film. I’m not at all interested in going to other places to check if it’s better or worse and everything, once you are in a place with what I thought was really interesting. Kristina was telling me she has this very strong experience. She suddenly found that she talked with other women in the commune, that she talked with the nurses, that she had a woman surgeon, that it was all this world that was so interesting, and so strong. I was told and shown. That’s why the idea was that the hospital was a tale, that it was the way to say all these steps that women go through whoever they are, from youth to old age. That was my point of view at the beginning.

She asked me because she loved that film God’s Offices and it was the first time that a producer offered me a very good idea. In God’s Offices, it was family planning. It was all about younger girls who were coming and the community that was answering. It’s an association, it’s not inside the hospital. I had a regret, which was that some doctors and advisors in France would also follow pregnancy. Not only abortion, and not only contraception, and I didn’t record it. So it’s not in the film. It was for me the occasion to bring back the whole of the women’s body in one film that was for me very important.

The film is bookended by your entrance and exit at Hôpital Tenon. Why did you decide to include your surgery near the end of the film?

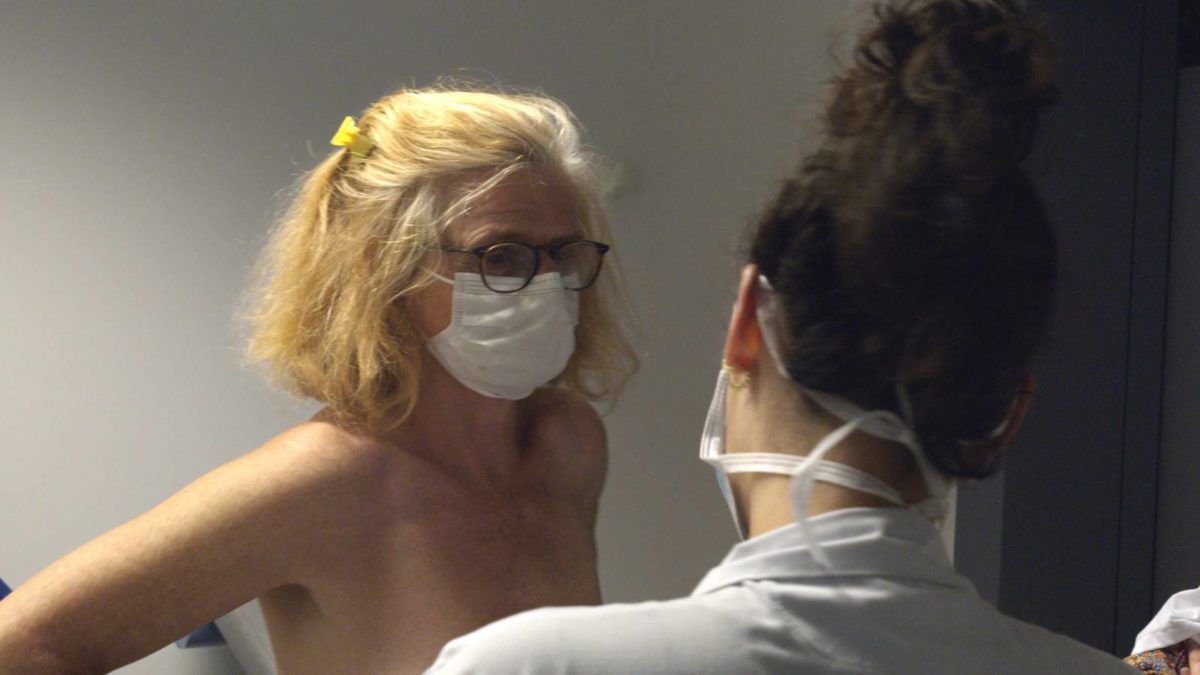

That was when it happened [at the end of production]. It happened to me after four or five weeks of shooting. It was important to show that I was not interested because I was sick. But because I was doing the film, suddenly I was sick. It was random. It was not at all organized and it was not autofiction that I got sick and then I was interested in other people; it was exactly the opposite. Then there was one thing that happened: meeting a very good surgeon of breast cancer before I knew I was sick. I told her I want to film a moment, a protocol that when you announce to a woman that she’s got cancer, or she’s got [something else]. When women come to see her, there is a doubt that there is cancer, but how big or maybe not all? “She told me yes, you’re right. It’s a very important moment.”

But I can’t go in the waiting room saying, look, I’ve got a small crew of documentary filmmakers in my office and will you accept to be filmed? And then tell her, “Look, you’ve got terrible cancer.” It’s not fair. It’s not correct. I completely understood that this moment was not possible to film it. I got sick and then I thought “Okay, then I have to go through a lot of exams. The doctor will receive me and tell me what I have and this is the announcement.” And so I could feel my own announcement because I was into the film. And of course, I wanted it to be filmed. So that’s why I decided I would be filming the announcement. Then I did another shooting, which was how I would get the surgery and I was naked. I thought that I filmed a lot of women naked. I did the same because everyone is on the same level.

Frederick Wiseman comes up in a lot of reviews of your films. How has he influenced you?

Well, I admire a lot of his work and we are friends lately. But I think I’m very different. Because he does the sound and I do the camera. I’m the camera person in all the films, whether they’re fiction or documentary. I think we don’t have exactly the same approach but I really admire his work. But on the topic of hospitals: he has always filmed hospitals as a place, an institution. And this was not a film about the hospital that I was doing. It was a film about the patient, the women patient, and the hospital is a tale. It was the way to have everyone in the film. I could have taken another tale. But it was very complicated. So it’s very different.

The hospital in my film is just a corridor. You see the corridor, and you can see the people who are in the hospital. But that’s all. Even though I did, I’m not filming the problems of the hospital, the nurses, the problem of money, and the problem of shutting services. There are lots of problems. But this was not my aim. My aim was to tell the difference [between genders]. As [Simone de] Beauvoir said, we are individuals, men and women, but women have this burden of the reproduction of people. Because of their gynecological nature, they have to go through a lot of problems that men don’t have. I remember this woman, this philosopher who told me, “Men go to the hospital when they feel bad, when they are sick, and women when they are well.” Which is true. I wanted to show this arc of life.

And also, what I believe in cinema is showing is okay. You know what a transgender person is, but you’ve never seen their consultation. You know what a little girl at age 15 wanting [their baby] after being pregnant, but you’ve never seen that consultation. You know what giving birth [is like], but you’ve never seen so many. You’ve never seen a C-section, you’ve never seen such material. You’ve never seen a consultation with the girl saying I prefer to suffer and to desire than the contrary. You’ve never seen the surgery and then you see what is endometriosis? You see it, really you see the flesh. And this is so important.

For me as a patient, I like to see, like ERT (Estrogen Replacement Therapy)––you’ve never seen what is taking the oversight. What is putting spermatozoa into ice and you’ve never seen the lab girl saying “Oh, this is an oversight.” I believe in cinema as something very strong as what it is to see things like the meeting of the doctors between them––you know the cancer doctor, the surgeon, the radio doctor, and they all discuss the cases. I had never seen that. I think for me, the fact to show those words, because all the time in a hospital you have the relationship between word and body. The words are the way to know the body, but you have to see the body. I was so amazed when I began to film surgery and those images, I thought “Oh, my God. I can’t understand [what is] inside the body.” It’s not at all like the drawings I used to do when I was at school. I don’t recognize anything and they do anatomy all the time. They say, “Look, this is it. Be careful. You don’t have to be careful of this part. You have this vein.”

I remember it’s not in the film, but I filmed a traditional surgery with a knife. The doctor would say to his assistant, “Can you draw me this vein? Yes, you are in the right place.” So it’s constantly a relationship between the knowledge which is in word and the flesh, and you have to recognize and understand how you name things in the body. I think it is very strong. As a patient. You have to know [your body] parts, how they work, and to visualize it. That’s why I did the film. Also, I was always thinking, “I have to film the body. I have to film that.” Because the moment you take off your clothes in front of a doctor is a very important moment. The fact that a woman who is Muslim, she’s got the veil. She’s completely covered and then we see a big pregnant tummy. I love to show that under the veil, there is a big tummy of pregnancy. I love that.

That’s a metaphor for many things. How did you contextualize showing the consultations and surgeries? It can sometimes be vomit-inducing when seeing surgeries on screen.

Well, I’m curious. I am interested. I want to know how it works. The first time I filmed surgery, I was really afraid that I would be scared and I couldn’t film. I’m not at all a camera person that goes into war and things like that. But then it’s this relationship between words and the body, you said “Oh, she’s pregnant,” and you think about c-sections for example. You think “Oh, they open the body and take the babies.” Then suddenly, you realize it’s much more complicated and that is probably more difficult than the normal [depiction of] giving birth. But you think “Oh, they are opening the abdominal muscles.” Then you see the water inside the tummy that goes up. Then you see those babies coming out and you think, “Oh my god, that they’re dead. Oh, no, they’re alive.” So it’s important to understand what’s going on. For me, it’s really important. It’s this relationship with words: you’re afraid of the words, then you see the body, then you understand.

The 2020s have been marked by the pandemic and hospital documentaries, like 76 Days (2020), The First Wave (2021), and De Humani Corporis Fabrica (2022). How do you see your film in relation to this canon of films?

I’m not making a film about a hospital. I’m making a film about women, patients, and the women’s body. I think most of the films about hospitals are not about patients at all. In my film, I realized it’s a lot about our civilization, like the way the doctors talk together. ERT, the fact of COVID, and making love is cut into slices. I think it’s absolutely amazing. What I think––and I said that Wiseman too-–is that we are making films for the margins so that they understand how we live. This is our civilization. I love to understand our civilization, what society has done. I remember the first time I filmed the doctors, I was thinking of Venice and the doge. All the people who were the governors of Venice in the 15th century, but they were only dealing with religion. They had this power because they were representing God.

These doctors work from six in the morning to 10 at night. They know they can discuss certainly there is a case and they say “Oh, but yesterday there was an article in an American review that says maybe we should change our point of view and everything.” So you think these people are so wonderful. They have so much knowledge. And why? Because they’re facing death and life. This is much stronger in a way. I mean, they have the doge in Venice, they only had power and they made fear about God. But here it’s every day the doctors, they have this threat of death and try to keep people alive and to understand how the body works. I thought it was absolutely marvelous. Even though my father has been ill all his life, he had multiple sclerosis. I was really not an easy person with the doctors because he had to fight for different reasons with doctors. He was looked after and I was amazed by our civilization, the science and it can bring a lot of problems. In France, the hospital is free. There is supposed to be no social difference between anyone in the hospital whether it’s racial or social differences. A bourgeois woman is treated the same as a homeless [woman] and I could see that. It is true. When I came into the hospital, I felt I came into a world that didn’t exist outside.

Our Body is now playing at NYC’s Film Forum and will expand.