Pasolini included an “essential bibliography” in the opening credits of Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom, proffering five philosophical titles by the likes of Roland Barthes and Maurice Blanchot to help viewers navigate his rich and daunting Sadean masterpiece. The closing credits of Arnaud Desplechin’s Ismael’s Ghosts also feature a reading list that could be called essential. Of the four authors listed therein, one in particular might hold the key to interpreting Desplechin’s exhilarating, overflowing mindfuck of a movie: Jacques Lacan.

Desplechin has frequently acknowledged his debt to psychoanalysis in general and Lacan specifically, but never had he dared plunge as deeply into the mysteries of the psyche as he does here. The hyper-dense complexity of Ismael’s Ghosts may be his attempt at a cinematic representation of a nervous breakdown, namely that of the protagonist Ismael (Mathieu Amalric), a director who gets stuck at a creative impasse while working on a film whose narrative harks back to the diplomacy / espionage subplot in Desplechin’s My Golden Days. At the start, it seems as if Ismael’s film is based on the life of his brother, Ivan (Louis Garrel), a diplomat who mysteriously disappeared years back. This is later brought into question when Ismael’s surname is revealed to be Vuillard, whereas Ivan’s is Dedalus. (Desplechin fans who enjoy recognizing these names from the director’s previous films will have an absolute ball watching Ismael’s Ghost, which is chock-full of such self-references – more on this in a bit).

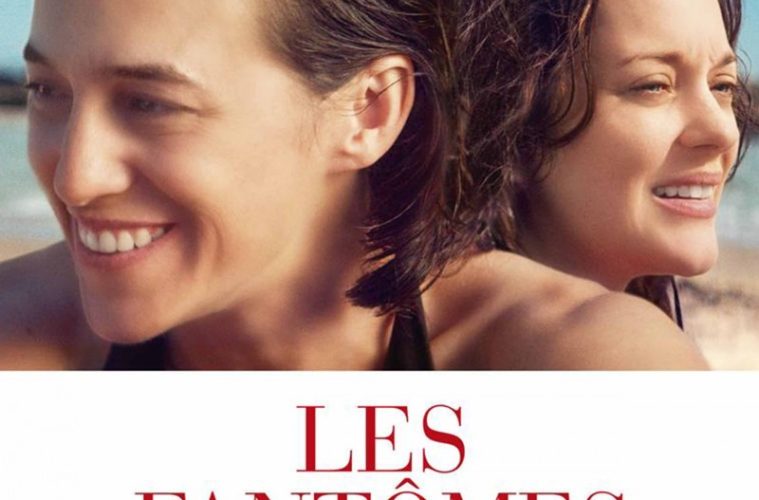

Although this confusion is left unresolved, it’s likely that Ivan is Ismael’s alter ago rather than his brother – “the reasonable one,” as he one at point describes Ivan – and that the film he’s working on, with its numerous parallels to his own life, represents an attempt at exorcising his many demons. Desplechin constantly destabilizes the viewer’s grip on reality through such tactics, and there are numerous other characters who also seem to be fabrications of Ismael’s psychosis, gradually emerging as the ghosts of the title. Central amongst these is Ismael’s wife, Carlotta (Marion Cotillard), who disappeared 21 years prior. Although she had long been assumed dead, she mysteriously returns, further damaging Ismael’s already brittle constitution and threatening to wreck his current relationship with Sylvia (Charlotte Gainsbourg).

The disorientation is amplified through an intricate narrative structure. Apart from two instances, which in retrospect come across as tongue-in-cheek, the many chronological jumps are never signposted. The story doesn’t just leap back and forth in time; it freely switches between reality and fantasy, and also frequently dives into the film-within-the-film – both as a script being written and as a shoot in progress – which, in turn, has its own flashbacks and recollections. Far from mere ostentation or playfulness, this proliferation of narrative layers, each drawing from the recesses of Ismael’s psyche, has a clear purpose: cumulatively and forcefully, it renders the impression of someone assailed by the past to the point of being incapable of functioning within the present.

If so inclined, one could easily take the interpretation of all this layering a step further. The fact that Ismael is a director working on a film very similar to My Golden Days, haunted by countless intertextual references from across Desplechin’s oeuvre, and given to regarding the world through the prism of Desplechin’s favorite films – Hitchcock’s Vertigo gets a particularly overt nod – suggests rather obviously that Ismael is a stand-in for his creator, even more so than Amalric’s previous Desplechinian incarnations. Perhaps making Ismael’s Ghosts was then an act of self-psychoanalysis by the director, an idea that he both encourages and casts doubt on by naming his protagonist Ismael as a reference to Melville’s Moby Dick, whose protagonist was also frequently confused for the book’s author.

Moby Dick isn’t the only literary masterwork evoked via a character’s name. By including both a Dedalus and a Bloom in his film, Desplechin makes explicit reference to Joyce’s Ulysses. Though wildly immodest, the implied comparison is not entirely inappropriate. With its vast cast of characters, constantly shifting planes of reality, and overabundance of citations and allusions, Ismael’s Ghosts is inevitably bloated and disjointed. But, like Ulysses, the film’s sheer scope and ambition, as well as the panache of its execution, render it intoxicating and immensely fun to get lost in. It’s also a work whose pleasures and complexities can’t be fully grasped or appreciated in a single viewing, validating the final exclamation that gives way to the closing credits: “Encore!”

Ismael’s Ghosts premiered at the Cannes Film Festival and will be released by Magnolia Pictures on March 23. See our coverage below.