With his exceptional trilogy on the Augusto Pinochet dictatorship – Tony Manero (2008), Post Mortem (2010) and No (2012) –Chilean director Pablo Larraín proved himself a trenchant commentator on his country’s problematic past. He turns his attention to the problematic present in The Club, a scathing j’accuse directed at the institution of the Catholic Church that represents his most uncompromising and vociferous film to date.

In a languid prelude, Larraín lulls us into what appears to be a pleasant, perhaps even feel-good narrative. Four elderly men and a woman train a greyhound on the beach of a small seaside village, racing him and timing his speed with enthusiasm. They enter the dog in a race, which he finishes in first place, and they return to their shared home, where they celebrate their victory and fantasize about competing at national level. Yet, there are subtle indications that something is off below the surface of this quaint domesticity. Why does only the woman attend the race while the men watch through binoculars from a nearby hill? Afterwards, why does one of them diffidently ask her if they couldn’t all share the winnings for once?

Then, with the arrival of a fifth man, the film effects a savage tonal turnaround. Just as it’s revealed that all the men are priests, sent to live in the house to repent for unspecified crimes, a bearded vagrant starts screaming from the street, calling the newcomer by name and demanding that he come outside. As the group remains inside, petrified at having been discovered, the vagrant’s screaming turns into a relentless recital of abuse, enumerating in explicit detail the numerous sexual acts the priest had forced him into as a child. This lengthy and horrific tirade is brought to an end by the sudden violent death of the accused priest, setting the film on its central course.

A new character is introduced, Father García, a young and sternly upstanding priest who’s come to investigate the incident and assess the viability of the house as a place of repentance, rather than a mere sanctuary from justice. “He wants to change the Church,” says one of the older priests in apprehensive anticipation of Father García’s inquest. “The Church is 2000 years old, I like it the way it is.” As signaled by the vagrant’s candid disclosure, Larraín’s intention is for his film to engender a confrontation with unpunished crimes and expose the deception and embellishment of official discourse. This is further underlined when Father García interviews each of the others about their past and they are framed in tight close-up, confessing directly into the camera.

In addition to molesting children, the priests are also revealed guilty of having collaborated in the imprisonment and torture of opponents to Pinochet’s regime. Though the latter atrocities ground the film in Chilean realities, the issue of Catholic priests’ sexual misconduct extends the critical scope to a global level. Moreover, in light of recent events, it’s impossible not to associate Father García’s reformist agenda with that of Pope Francis. The house’s microcosmic function is evident as is the representative role of its inhabitants, whereas the vagrant, who is mentally unstable and keeps plaguing the priests throughout the film, embodies the traumatized psyche of the manifold unavenged victims.

One of Larraín’s great achievements is to seamlessly integrate this clear allegorical configuration into an engaging narrative. The symbolism is immediate but never feels forced or schematic and thus results in something all the more powerful. Despite the unequivocal nature of the atrocities, Larraín endows his characters as well as their actions with ambiguity, disallowing facile conclusions. This approach is reflected in Sergio Armstrong‘s cinematography. As bleak as its subject matter, the film’s visual tone is dominated by cold colors and the images are pale and washed out, giving the impression that a fine mist always hangs in front of the camera, an effect that is reinforced by deliberately keeping some shots slightly off focus.

It’s also remarkable that the entire film is peppered with instances of pitch black humor, eliciting laughter both genuine and thoroughly unsettling. Lest there should be any doubt about the gravity of the material, however, the narrative builds up to a climax of traumatizing violence and intensity when the priests demonstrate the extent they are willing to go in order to safeguard their fraudulent façade. Though profoundly upsetting, The Club’s assault on institutionalized hypocrisy never risks feeling unjustified.

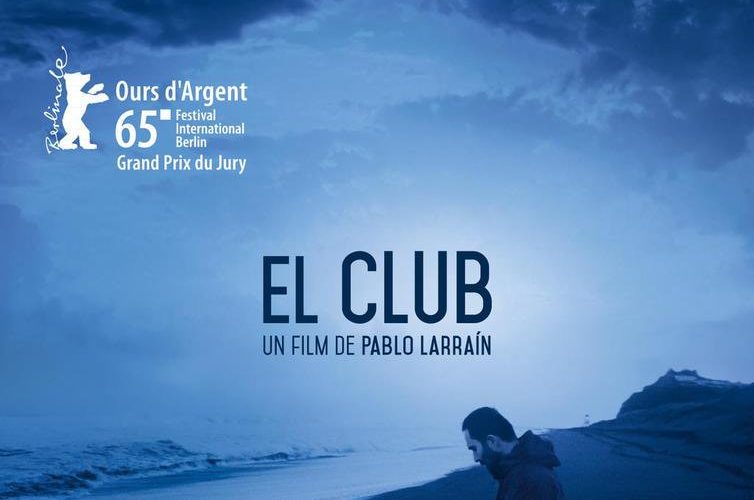

The Club premiered at Berlin Film Festival and opens on February 5.