A full seventeen years after Gael García Bernal came to the attention of international audiences with Y Tu Mamá También we find the ageless wonder once again playing an idealistic young man who is accused of jerking off too often. The film in question is Museo, a dramatization of–or, as the film cheekily states, “replica” of–events that took place in 1985 when two young men stole a bounty of priceless Mayan artifacts from the national museum in Mexico City on Christmas Eve.

It is the latest work of Alonso Ruizpalacios, an obliquely political filmmaker with an eye for cinematic homage. His latest is essentially a heist movie, but it’s one that utilizes those strengths in order to subvert the conventions of an overly familiar genre. In doing so, however, it forgoes a little bit of what provides that type of filmmaking with such narrative élan.

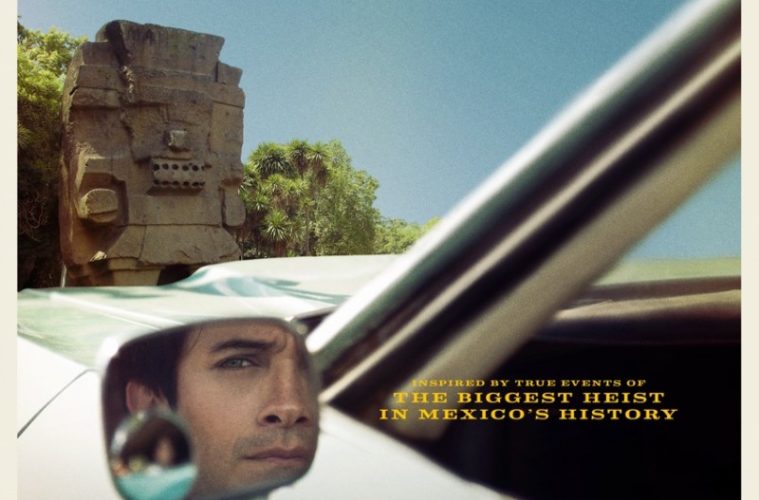

Ruizpalacios’ robbers are called (inaccurately) Juan Nuñez (Bernal) and Benjamin Wilson (Leonardo Ortizgris)—the latter also functioning as the story’s narrator. We hit the ground running a number of years before the fact with startling news footage of a giant Mayan statue of the god Tlaloc being hauled from its original site and taken to the capital where it is to become the crowning piece of the new Museum’s collection. This is the exhibition that a young Juan will soon visit with his dad. Ruizpalacios’ film is chiefly concerned with the morals of such crude cultural acquisitions and so when Juan’s father informs him that the idol has been pilfered, the seeds of skepticism are sown. This uneasy question of what exactly is national heritage and what is simply colonialism will prove to be Museo’s most pondered and openly ambiguous topic.

It is a terrifically enticing prologue and the retro-leaning credits sequence that follows–backed by the yearning strings of Flight of the Mayans–suggests that a Spielbergian adventure might be on the cards. However, thanks to a rather long-winded Christmas party sequence that immediately follows, a great deal of that momentum is soon lost.

Ruizpalacios’ debut Güeros was celebrated for its canny use of cinematic pastiche, mainly relating to the Nouvelle Vague. With its clever, well-executed nods to Bruce Lee and Scorsese, amongst others, Museo is certainly not found lacking in that department. The heist sequence alone is a confident mix of visual inventiveness and nods. What the film does lack, intentionally or not, is a clear moral arrow. Indeed, the men’s motivation for committing the robbery is never quite explained. They are at first amazed with having acquired such prized items but quickly decide to shift them on the black market, relocating to Acapulco and indulging in all the things that such a locale, especially in the mid-‘80s, had to offer. They appear at certain points to be inspired by feelings of cultural injustice but later discussions suggest that simple boredom and, worse still, shallow finance were what really drove them. It could be that Ruizpalacios hasn’t quite figured it out for himself, either.

Later in the film Simon Russell Beale cameos as a high-flying collector of ancient art named Frank Graves, a man upon whom Juan and Wilson hope to unload their priceless stash. During the negotiation, Juan insists that he does not want to see the artifacts end up in the British museum–a righteous stance but given his position, somewhat laughable. Graves regales them with a story about a Spanish conquistador vessel that sunk along with its half-billion dollars’ worth of Peruvian gold. It was discovered centuries later on the ocean floor by an American expedition and Graves alleges that all three nations attempted to claim ownership of the lucrative cargo. The question of rightful possession of such things, as far as the man is concerned, is a riddle without an answer. Ruizpalacios’ film asks similar questions but is, in the end, no less frustratingly impartial.

Museo premiered at the Berlin International Film Festival and opens on September 14.