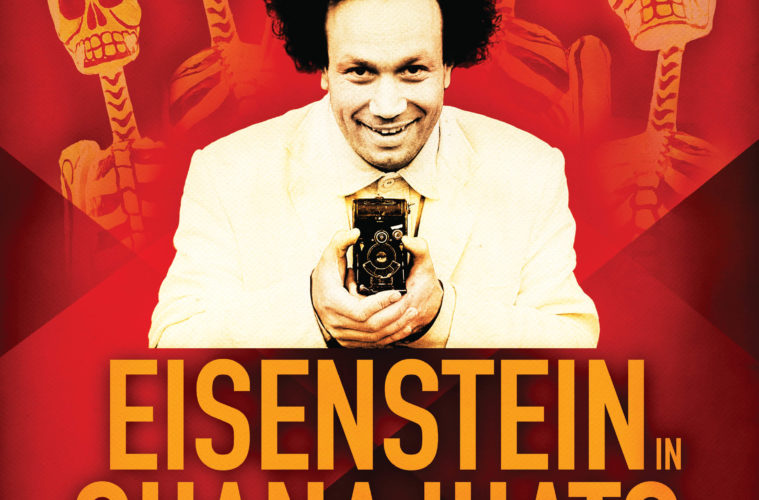

From today’s vantage it’s difficult to believe that in the 1980’s Peter Greenaway counted as one of the hippest auteurs around. After bursting onto the scene in 1982 with The Draughtsman’s Contract, his subsequent features were always the subject of vigorous hype and discussion upon release. Then something happened at the turn of the decade and his films became exceedingly self-indulgent and alienating, scaring off distributors to the point of barely making it out of the festival circuit anymore (2012’s Goltzius and the Pelican Company, anyone?). While the completely bonkers ‘biopic’ that is Eisenstein in Guanajuato is unlikely to fare all that much better with distributors, the long-heartbroken fans that do manage to see it will rejoice to find Greenaway deliver his most enjoyable film in nearly thirty years.

Ostensibly, Eisenstein in Guanajuato is a chronicle of Sergei Eisenstein’s ill-fated endeavor to shoot a film in Mexico at the age of 33. However, not only is Eisenstein never shown shooting a single scene, but anyone without prior knowledge of the Soviet master is unlikely to come out of the film much wiser about his life or place in film history. Rather, in paying homage to one of his heroes, Greenaway delves into the director’s personality, offering an interpretation radically different from the customarily-held image of Eisenstein as a solemn and cerebral revolutionary genius. The biographical focus, unsurprisingly, is on Eisenstein’s sexuality, whereas his groundbreaking film techniques and theory are explored visually through a conflation of Eisenstein’s method and Greenaway’s own.

Given that Greenaway has access to filmmaking resources that his predecessor never did, he goes all out in trying to imagine what Eisenstein might have done with these modern tools, all the while retaining an aesthetic that is unmistakably his. The most obvious nod to Soviet montage is the recurrent use of images or clips representing what the characters are saying. For instance, whenever a historical figure is mentioned, a real photograph of the person is inserted into the frame. Instead of being gimmicky, this device has the effect of instantly grounding the narrative within historical reality – as is conventionally done post-hoc through a slideshow of historical pictures in the closing credits – giving Greenaway license to take his biopic in the wildest directions without ever fully dissociating from his source material.

This is the most straightforward stylistic appropriation. Otherwise, Greenaway attempts to stretch the possibilities of editing to their limit, going through a staggering catalogue of techniques that would be impossible (and futile) to list here, and doing so at a pace so frenetic, the hectic rhythms of Eisenstein’s own montages are rendered positively languorous by comparison. Inevitably, the film can be overwhelming and a great number of the experiments are failures. On two or three occasions interiors are not filmed directly, but rendered by stitching together several stills into a three-dimensional environment (think Google Street View), which the characters are then placed in via greenscreen – the result is ghastly. But then, for every such flop, there’s a dozen resounding successes. One long lateral tracking shot, which feels like a revision of those that dominated Greenaway’s 1989 masterpiece The Cook, the Thief, his Wife & Her Lover, is particularly astonishing. While Eisenstein is having an impassioned argument with his producer, shouting and prancing around a palatial room in furious agitation, the camera effects a measured leftward dolly movement, often passing in front of large columns that vertically split the frame. Some of these columns are used to splice together shots of different rooms of the building as well as its terrace. The argument is thus depicted continuously over several minutes, at times in duplicate during room transitions, and the camera travels through the building, out the front, makes a 180-degree turn on the terrace, and then goes back inside, all edited together seamlessly and without changing the direction of the tracking shot.

Elmer Bäck’s performance as Eisenstein is exceptional, his manic energy somehow able to match that of the film’s visuals and achieving a synergy of exuberance. His full dedication to the script, which expects manifold humiliating excesses, is also remarkable. Full, unflattering nudity is a prerequisite for virtually every Greenaway actor, but never has one had to go to Bäck’s extent, which includes losing his virginity in a scene that competes with Blue Is the Warmest Color for the title of longest and most explicit homosexual sex scene outside of pornography (perhaps not so coincidentally, even the framing is strikingly similar). Although hilariously puerile – in flagrante, the couple discusses syphilis at length, and afterwards, Eisenstein compares popping his cherry to the storming of the Winter Palace – the film’s continuous emphasis on sex is not without purpose. While it doesn’t shed quite as much light into Eisenstein’s creative psyche as Greenaway would doubtlessly argue, it is nevertheless a pointed defiance of the official discourse on Eisenstein in his Russian homeland, where he is celebrated as a national hero but his homosexuality has always been denied.

Eisenstein in Guanajuato premiered at Berlin Film Festival and opens on February 5th.