Hours before I place my trust in a rush-hour F train departing from Herald Square just 19 days before Christmas, I am speaking with scholar and filmmaker Jerry Carlson about David Bordwell and Orson Welles’ Filming Othello. Nominally a chronicle of Welles’ time adapting Shakespeare’s play, the documentary’s stream of inconsistencies and outright fibs linger with the late critic. Carlson pauses in his recollection and conjures Bordwell’s exclamation post-screening: “You can’t trust a thing this man says!”

Welles’ instinct for storytelling was matched only by his affection for lying. I suspect he assumed these two phenomena were basically linked, two sides of the same coin pulled from an ear. You could do worse than have Welles on the brain on a night when Elaine May would appear in front of a theater audience. Would she appear? We were told she would, following a 6:00 PM screening of her sour, slick-streeted panic attack Mikey and Nicky. May would be in conversation with longtime film and television editors: Phillip Schopper, a collaborator and confidante, and Jeffrey Wolf, who worked in Mikey and Nicky’s infamous editing room. There would be no audience Q&A, as I was solemnly reminded in a conversation with the two moderators on the prior Wednesday. “I mean, this is not a press event,” Schopper said. “And that’s very serious. We have given our word, meaning, [don’t] approach her for anything. In any way, even to the extent of asking questions.”

Elaine May doesn’t do press, goes the adage. That she was appearing in public was itself a rare occasion, demonstrated by the crackle of murmurs humming around a full-house’s worth of bodies, first in Metrograph’s lobby, then the theater itself. Would she show? Would she actually answer questions, honestly? Would she be encased in a bubble, Jake Gyllenhaal-like? The evening was being presented in conjunction with American Cinema Editors, of which Schopper and Wolf are both members. “I knew that Phillip was involved from the documentary end,” said Wolf during our conversation. “I came in from the narrative end. But we had Elaine May in common, and it seemed like a great opportunity to celebrate a singular career, particularly in the New York film scene,” to which Schopper added: “And she really is a terrific editor. She loves the process of editing. I think it’s closer to writing than anything else. I think it appeals to her a lot.”

Mikey and Nicky puts forth editing as a strategy that discombobulates living, rather than stabilizes it. The film sputters and bumps as if the celluloid itself is under the influence of its characters’ indulgences: domestic beer and Gelusil, betrayal and violence, spiking panic and simmering resignation. Nicky (John Cassavetes) is a wolf-smile gangster damned by an open contract to run down his clock in the company of his longtime, long-suffering best friend Mikey (Peter Falk), resentful and low and constantly making protestations about his relative civility. In effect—and by casting two of the most compelling actors to appear on movie screens in the 1970s or beyond—it is the story of two characters constantly editing their behavior, meting out half-truths and full lies to out-betray each other while simultaneously adhering to their friend like Peter and his separated shadow. That the two men reserve their most bilious behavior for the women and world around them is May’s crucial grace note; even (or especially) when they’re actively involved in offing the other, Mikey and Nicky still communicate best with Mikey and Nicky.

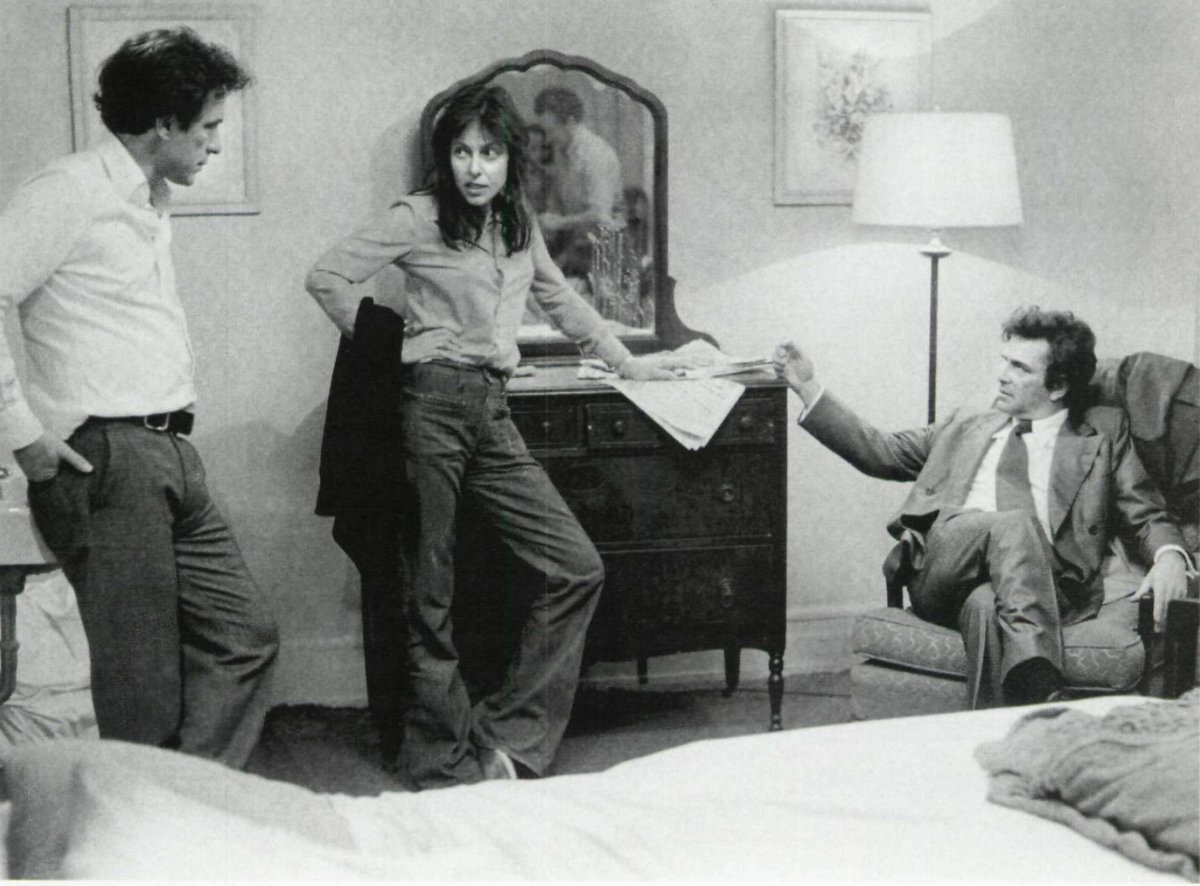

Elaine May and John Cassavetes on the set of Mikey and Nicky

In programming Mikey and Nicky as part of a series about editing, the obvious focus becomes the way the film was literally assembled, legendarily from roughly 1.4 million feet of film. In her definitive biography of the filmmaker, Miss May Does Not Exist, Carrie Courogen writes: “To put such an incomprehensibly large number into perspective: 1.4 million feet of film is 259 hours of raw footage… it’s 265 miles of film; the drive from New York to Washington, D.C., is 30 miles shorter.” The reasons for this glut of footage varied, from May’s decision to nix formal blocking and coverage with three cameras running simultaneously to a propensity to let takes run unfathomably long. “Elaine didn’t deal in quick takes,” Courogen writes. “Hers stretched on impossibly long, long enough that a thousand-foot load of film—which lasted roughly ten minutes—would nearly run out by the time each was done.” Cutting Mikey and Nicky from out of this superabundance would have been a task even if its birth wasn’t complicated by a director dragging her feet to the finish and Paramount dead-set on wresting control of the film from her. In Courogen’s graceful retelling: May sold the still-incomplete film out from under Paramount, not about to lose her final cut, which led to the studio suing May for breach of contract, which led to May’s countersuit, which led to an NY judge ordering May to surrender the film, which she sort of did, eventually, even if she maybe temporarily retained a reel or two as collateral, perhaps both literal and spiritual.

Wide-eyed, half-true versions of this punk behavior pervade the cinephile’s collective imagination. I include some version of it here because as soon as Mikey and Nicky reached its sour ending and Elaine May appeared to a raucous ovation—an always-moving phenomenon, given the multiplicity of heartburns Hollywood and other systems lobbed at her—anything resembling historical truth began to wobble.

“Ask me anything,” May said, perhaps the deadest-pan jibe of the night. “Where did this story come from?” Schopper asked, after exchanging some lighthearted—if herky-jerkily delivered—banter. “How did it occur to you? Is it something from life?” May responded with a provocation encased in a sidestep: “It occurred to me because I was thinking, ‘I know that if I did comedy they would like it, so I chose this movie.’ What is a movie that has no laughs?” May’s answer has the familiar motion of a punchline—I thought “What would be a hit?” and then I did the opposite!—but it betrays the stubborn radicalism of a career spent turning cars against their wheel’s better instincts, constructing a new kind of Hollywood moving image defined by volatile frisson instead of broad approachability. That Mikey and Nicky was born of counterproductive instincts is what makes the film a vital treatise on the spiky tension a certain kind of man inflicts on himself and the world. That the film tackles this thesis in the mouths of performers unwilling to conceive of life or acting without jokes is what makes it essential cinema instead of polemic.

Schopper kept driving towards the real-life inspirations behind Mikey and Nicky, a matter of public record discussed in the past to varying degrees of frankness. (The origins are delivered with honest ease in Courogen’s book.) May grew up in a Chicago ecosystem that included small and big-time hoods, terrain she eventually conceded to speak about at Metrograph: “The best friend always turned them in,” she recalled of some of her mob-tied neighbors with hits on their heads. “Always! How they didn’t remember that from the last time, I don’t know, but that’s what happened.”

In steering the conversation towards the film’s relationship to editing, Schopper noted its sense of economy. “You have said, I’ve heard you say, that when you write and when you make a film, no scene can be about one thing. A scene always has to be about more than one thing.” Again, a classic May parry cut in: “I didn’t say that, but it’s an interesting thought.” The jibe elicited a hearty laugh from the audience. Schopper had cited the advice just a few days prior (“She always says that you have to accomplish more when you write or make a scene: more than one thing has to happen”) in our videochat interview that found the two editors thinking aloud about their approach at the Q&A as much as it featured them discussing editing, either broadly or in relation to Mikey and Nicky. The veracity of who first spoke the dictum or whether it was true or not all seems less revealing than May’s instant instinct to cede or sidestep credit. I thought about David Bordwell. You can’t trust a thing this woman says!

On the set of Mikey and Nicky

I thought, too, about Courogen’s analysis of May’s attempts to distance herself from contemporary retellings of Mikey and Nicky’s birth, which seek to exalt her clarity of vision in the face of studio interference, that force most anathema to the creation of cinematic art. “Attempting to glaze over the incident is perhaps not as much an unwillingness to take ownership of a perceived negative narrative as an attempt to just make all the attention go away so she can continue to live her life unbothered, just the way she likes it.” When it came time to regale her audience with the saga of Mikey and Nicky’s stolen and hidden reels, May embarked on what could only be described as a revisionist traipse à la tight-ten improv sets. Mario Puzo was mentioned, criss-crossing Paramount executives emerged not unlike low-level mob hoods, lawsuits were liberally cited and then ceded space in the narrative. These events were—if not outright untrue—reorganized, even re-edited.

It’s a mistake to turn to the Q&A form for anything resembling truth, especially when the interrogated parties are known for storytelling proclivities. It’s a mistake to exalt “the truth” as objectively essential in a medium predicated on bending reality to evoke sensation, to forsake the interview form because certain parties are inclined—whether through self-selected memory banks or more personal motivations—to tell a story a given way. A contingency of truth is more vital to cinema than an image’s geometric proof—a film’s images don’t mean anything unless they move against its other images. At a certain point in the evening, as I watched my smartphone’s voice recorder tick through the 15-, 25-, 45-minute marks, I tried slowing down the chicken-scratched words that are completely illegible to me now. Sometimes it feels like we too-easily cede cinephilia to consumption and collection: if we can only witness a celebrated someone say something, we attach some of their supposed import to our own. Our alienation doesn’t feel so sharp, then.

These cynical feelings didn’t rear their ugly heads listening to Elaine May speak, however true what she said was. I looked around at an audience full of frankly beaming faces. I heard the scratch and tempo of a voice belonging to someone I’ve only ever heard through cultural objects, whether comedy albums or films. We hadn’t gathered at the cinema Q&A to address a question that could possibly be answered correctly or incorrectly. We were here to laugh, tentatively and hearty amid a world freighted with tragic inclinations. It’s a sensation not unlike being a small, low human half-attuned to their mortality, running around with a prankster they love.