How much of our ancestry is tied to the history of the places we call home? While some of us would probably answer “None,” we’d be wrong. Just because your family tree was lucky enough to exist on the periphery of major historical moments as bystanders doesn’t mean you haven’t been impacted by wars, tragedies, inventions, and art in ways that defined your choices and subsequently the choices of your children. Why did my grandfather immigrate to America from Lebanon (then part of Syria) when he did? How did my father not getting drafted to Vietnam influence my sister’s birth and my own? Where does 9/11 fit in as an Arab American who never had an ethnic option on forms to check besides “Caucasian” previously? History defines us.

With that said, however, some are embedded much deeper than others. One example is German documentarian Thomas Heise. His great-grandparents were sent to concentration camps during World War II. His parents’ socialist politics became a part of their identities in East Germany. And he and his brother Andreas ultimately followed along that path by spending time in the National People’s Army of the German Democratic Republic. Heise was a literal product of the political and social unrest his nation underwent courtesy of two world wars, genocide, shifting allegiances, and the eventual reunification of east and west that allowed his work to finally be shown within his own borders. He could create a film with historical resonance spanning over a century with nothing but his family as source material.

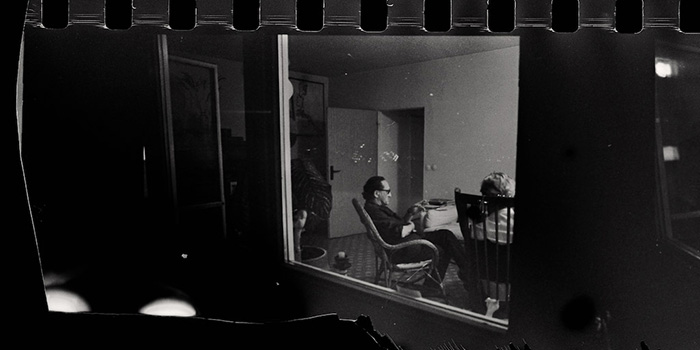

That’s exactly what he’s done with the almost four-hour essay film Heimat ist ein Raum aus Zeit [Heimat is a Space in Time]. Starting around the time of World War I when his father’s parents fell in love, Heise reads aloud from correspondence, diaries, and official documents to tell the dramatic, introspective, and often suspenseful tale that led him to this very same project. Told in five chapters with nothing but slow pans of archival photographs and documents (in color) or serene scenes from modern-day Germany with thematic or physical relevancy to the topic at-hand (in black and white), we learn everything there is to know about an entire country through the Heise family’s words. Some passages prove better than others, but none are inconsequential to the whole.

Chapter One is by far the most harrowing as a majority of its run-time consists of pages of names scrolling up the screen juxtaposed by letters sent to Thomas’ grandparents by his grandmother’s Jewish relatives. We know as soon as the dates start aligning in sight and sound that one of them will be included on the list, that person will stop writing, and it will only be a matter of time before another suffers the identical fate. The conceit is so simple on a sensory level and yet absolutely profound emotionally. The dread we feel knowing what’s coming only grows after the first name is underlined in red because the floodgates have opened and there’s no turning back. What’s worse: the letters’ recipients are helpless to intervene.

The chapter that introduces Thomas’ mother Rosie arrives with a bit more levity as it starts with the undying love between she and her beau Udo before life gets in the way. She lives in East Germany and he in West attending school, both dating other people with this notion that they’ll be together in four years. And as we discover Udo to be a selfish jerk, we also learn just how different these two halves of the same geographical whole have become. His words move from belittling her politics to the equivalent of sexting while her diary entries reveal her shifting feelings for him and every boy she meets until Wolfgang Heise. Socialism officially takes over as Wolf and Rosie stake their futures upon it.

Then we hear from famous family friends Christa Wolf and Heiner Müller (the Heises weren’t simply faceless neighbors on a street minding their own business) as well as Thomas himself. To describe what’s said in more detail would be a disservice to the eloquence and passion of what’s written because they all have such strong opinions and unwavering philosophies. Eventually things end with Müller actually name-checking Thomas by speaking about how fine the line is between extreme political leanings when every war is ultimately fought between the poor and the poorest. While those in power watch from their thrones (dictators, presidents, oligarchs, etc.), it’s the little people with unwavering philosophies that die while doing their bidding or the bidding of their identical replacement mirrored across the aisle.

Even if that seems overly pessimistic, though, it doesn’t negate the ways in which that emboldened energy and drive for progress pushes each Heise generation forward. It isn’t solely bloodshed either as we also witness the artistic through-line from Thomas’ great-grandmother’s sculptures to his father’s scholarly theses to his own cinematic success. Do politics also play a major role along that path? There can be no doubt. The Heises have been fighting battles for decades whether they were being shot at or not. And it’s these seemingly insignificant details that should be meaningful to their family alone that really blow this thing wide open because they inevitably represent so much more. We make and document history every second of our lives and no experience is less important than the next.

Heimat is a Space in Time screened at the Toronto International Film Festival and opens on March 13.