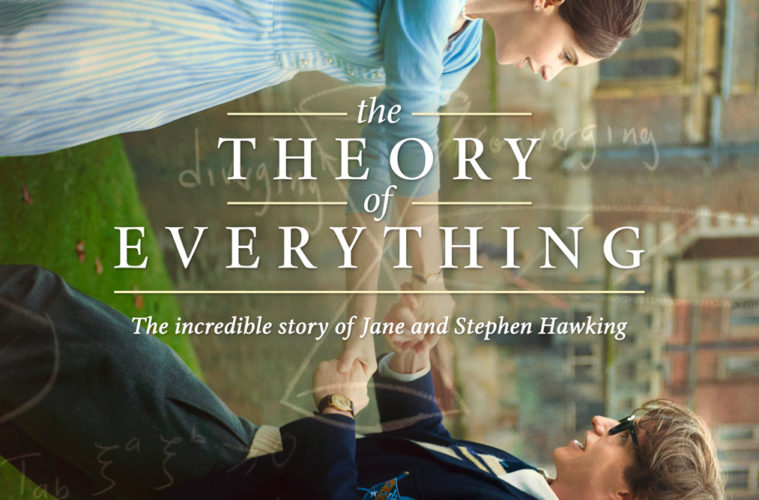

It’s almost become a given that those wishing to stand out must proclaim their biopic is an outside-the-box, innovative retelling of significant events in one’s life. Then again, few directors would outright state that theirs is one wading in conventional waters, content to merely provide an accurate, dry retelling of the figure they are exploring. Despite committed performances, The Theory of Everything falls more on the latter side, little more than an adequate, honorable portrayal of Stephen Hawking’s life thus far.

After a brief opening suggesting the seemingly required book-ends for this sort of effort, we’re launched into Cambridge circa 1963, were we meet Hawking (Eddie Redmayne) as he enjoys the freewheelin’ graduate-school life of biking, reserved partying, and the occasional study. While his significant achievements in the field of physics will crop up as needed, the main focus of the story is, of course, love. It’s at school where he becomes acquainted with Jane Wilde (Felicity Jones), a woman of faith studying foreign languages, and who would soon become his first wife.

Capturing with a glossy sheen to match the emotions Theory wears on its sleeve, director James Marsh does a sufficient job here, but with more than a few missteps along the way. Considering our knowledge of the motor neuron disease Hawking will be afflicted by — he’s initially given two years to live — early shots, pre-diagnosis, focusing on his legs feel cheap. There’s also a device employed in the final moments that may tie in with Hawking’s discoveries, but, applied here, gives the sense that Marsh doesn’t possess a confidence to assuredly conclude his story.

What comes before has a potent emotional center via Redmayne, who effectively showcases Hawking’s physical deterioration without ever feeling exaggerated. His loss of speech and declining ability to properly move are gradually introduced into the performance, superbly acted and devastatingly escalating. Throughout this, though, we could have used more of the inverse relationship as he becomes one of the world’s smartest physicists. Credit also goes to Jones — her aging is far from believable, but the turn as Jane Hawking (whose memoir the film is based on) successfully depicts the difficult balance between devotion and dedication to her husband and their children while longing for a normal life.

That temptation comes in the form of Charlie Cox‘s Jonathan Hellyer Jones, a handsome widower who befriends the family, reciprocated later down the line for Stephen Hawking, with his nurse Elaine Mason (Maxine Peake). Before this pair of extra-marital romances come to a head, we’re given the finest scene of the film: Jane and Stephen have what is seemingly their last substantial conversation as a couple, serenely realizing their relationship has reached its end.

Dealing with universal, substantial themes of religion vs. science, along with love and loss, one wishes the film’s execution could be as bold as its ideas, but what we’re given is a conventional, congenial attempt to convey a lifetime. For relying more on emotions than the fascinating knowledge contained in Hawking’s mind, The Theory of Everything could’ve employed more complexity.

The Theory of Everything opens on November 7th.