It seems odd that there should be anything left to be said in a movie about cops. It seems as though the cinematic landscape has been saturated by police officers and detectives, their lives and work dissected and examined to the point of obscenity. Yet we as an audience remain enamored with the life, the job, all the facets of the existence of the people who swear to protect us.

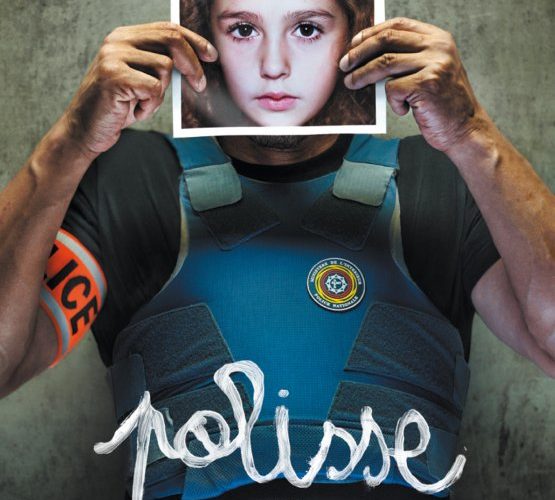

Polisse, written and directed by Maïwenn, provides one of the most novel and engrossing new entries into the genre in quite a while, and more than defends and justifies its creation.

Part of this has to do with the subject not only of the film’s narrative, but of the investigations we follow. The film focuses on the men and women of the Child Protection Unit (CPU) of the Paris police. These are the people who have to investigate the various forms of exploitation of children, from incitement to commit crime to sexual assault and physical abuse.

Rather than following a specific case and using that as a narrative thread, this film follows the unit as a whole, throughout a number of incidents and trials, all of which become resolved with varying degrees of difficulty. We see that it is not a single case that really wears on any member of the unit, but the consistent and ceaseless parade of toil and strife and misery around them.

We see their home lives, each strained and contorted in its own way to fit around and outside of their job, but never alongside or within it. Marriages are tested, children are estranged. The only time they seem to feel at ease, or find any kind of comfort or normalcy, is amongst each other. The performances in this film are understated, but powerful. We can see and feel the camaraderie amongst the detectives in every move and glance and word. It really does feel as though this group of people have served and suffered together. To see the marked difference in their attitudes among their civilian friends or relatives and their time on the job or out after the shift is incredible.

The interpersonal dramas that arise from the tension between work and life also make for compelling viewing. One detective is undergoing a rocky divorce, and she takes solace in the words of her partner. As time goes on, however, the variance between what she feels and knows is right and what she takes on faith from her partner begins to wear on her. The war between external life and the iron bonds forged by their seemingly unfathomable jobs is not easy, or pretty, nor readily resolved. Likewise, a romance between one detective and the photojournalist following his unit is marked and nurtured only by the progress the journalist makes in understanding an ingratiating herself to the unit.

These are large ideas, heady and existential questions as to the nature of what people must sacrifice in order to serve and protect. The film is wise to stay away from the usual tropes of the genre, choosing instead to fully immerse itself in the lives of its principles. Likewise, focusing on the actual day to day reality of their jobs, and showing the unending trot of victims and perpetrators through their precinct, keeps the film from ever feeling like another procedural showcase. The horror becomes routine, the shock becomes a drudge.

So while it may seem as though there is nothing new to be done in the police genre, Polisse proves that by not over thinking it, by simply allowing veracity and nuance to win out over the impulse toward bombast, it is possible to say a lot that is not only poignant and insightful, but surprisingly novel.

Polisse is now in limited release.