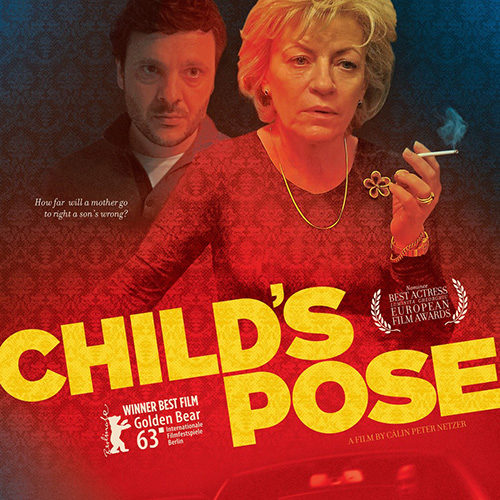

What does it mean to be a parent? To take a blanketed, personal responsibility for the good and the bad of your child’s actions? This question is at the heart of Călin Peter Netzer‘s Golden Bear-winning film Poziţia copilului [Child’s Pose], not just the singular relationship of lead actress Luminița Gheorghiu‘s Cornelia Keneres and her grown son Bardu (Bogdan Dumitrache). There is that—her overbearing matriarch refusing to let her only child out of her clutches despite his trying to move on and create a family of his own—but when he accidentally kills a young boy crossing the street, while speeding past another car, we watch their resentment tinged “love” compare with the victim’s family’s heartbreak to discover just how far a parent’s reach infers upon a child’s decisions.

The incident could have been prevented, as Barbu was speeding, the deceased was recklessly crossing a freeway in the dark, and the man Keneres was looking to pass (Vlad Ivanov’s Dinu Laurentiu) could have simply not engaged in the patient road rage of standing his ground. Seeing Cornelia’s reaction when told Barbu had been in an accident is one of pale helplessness so we can only imagine what the boy’s father (Adrian Titieni) and mother (Tania Popa) felt after hearing their much more tragic news. It’s a horrible situation where blame lies with multiple people and at a certain point one must let go of the anger and selfish fight to understand the hurt of those on the other side. Cornelia, however, only sees how she may lose her son completely to prison. So she reacts.

And in this microcosm of her attempting to “fix” the situation with well-placed friends in government, we see the ruthlessness to her maternal instincts. She has no problem talking back to the police officers on the case taking Barbu’s statement (Mimi Branescu and Cerasela Iosifescu) or verbally sparring with the victim’s distraught uncle. She has no shame in letting the predicament give her totalitarian control: snooping around her son’s home under the auspices of collecting his things so he may stay with her, finally having reason to usurp the power of his girlfriend Carmen (Ilinca Goia). This is her chance to be the hero and she quickly forgets the bigger picture of what occurred. Rather than comfort her visibly distraught son, she begins bossing him around to do what’s necessary to manipulate facts so as not to lose him.

The rub, however, is that she only pushes him further away like always. We wonder if Barbu’s germophobia is a direct result of her babying him during youth. What if Carmen’s powerful monologue about her relationship being in flux because of Barbu’s changed attitude towards having a baby goes hand-in-hand with his not wanting to do to a child what his mother did to him? It also shouldn’t be disregarded that the family psychologically damaged enough to need a manslaughter charge to bring them together (days after Cornelia’s birthday couldn’t) remains physically intact while the one with a father willing go to jail if his inability to teach his boy how to cross the street properly was the key cause to his death gets broken. Somehow Barbu surviving is more punishment for the Keneres than not.

These are the familial examples Netzer and co-writer Razvan Radulescu put on display. We watch as attitudes get warped, compassion removed, and grief’s all-consuming power possess victim and perpetrator alike. You see it in Gheorghiu’s quiet moments alone chain smoking, ignoring those she doesn’t want to talk to and conniving ways to come out clean. You see it in Dumitrache’s shocked silence and tearful eyes staring into the distance as he attempts to comprehend what he’s done—reconciling the pain and sorrow against his mother force-feeding maneuvers that pretend he’s without fault despite his heart saying otherwise. How many times can you recall someone’s “help” only exacerbating a situation? It happens all the time because people forget the lasting pain underlying their desire for present salvation. Jail is meaningless when the face of a life taken cannot be shook.

Gheorghiu owns every frame whether telling Barbu to lie in front of the cops he’s already told the truth, meeting the obviously sociopathic Ivanov to gauge what’s necessary for him to corroborate that lie, or meeting the victim’s parents while funeral arrangements are still being finalized. The latter moment—taking up the film’s final twenty or so minutes—brings every emotion and misguided (yet well-meaning) action to a head as two grieving parents sit with a rawness that transcends acting. It’s every parent’s nightmare to have a child taken through circumstances out of their control. We try so hard and make as many mistakes as sound decisions along the way before discovering we have little control. We’re only left with guilt and regret whether we lose our kids or have them taken away; love always one fateful step from hurt.

Child’s Pose opens today in New York and February 21st in LA.