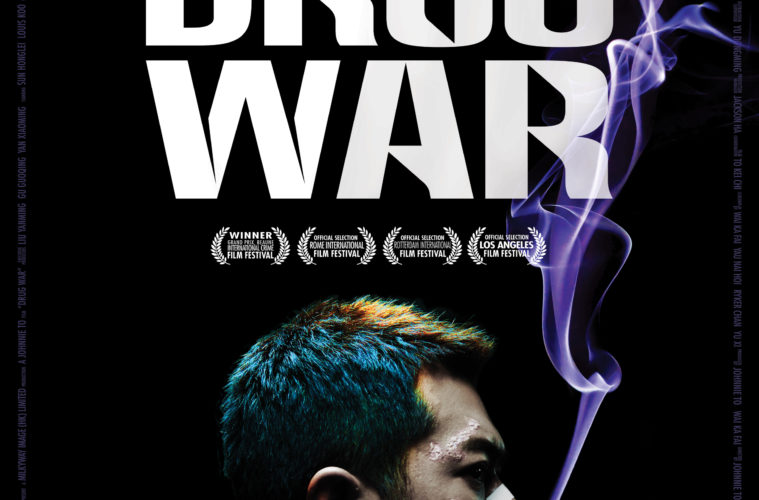

Lines and lines of information weave in and out of each other at a pace far too liminal and frantic for any one person to be on top of any single thing at any given moment — an infrastructure built on the paradoxical give-and-take of data heaps clouding the human judgement of moral superiority. These are not the CIA operations of Zero Dark Thirty, but the day-to-day flow of the Hong Kong police force in Drug War, a crime drama — from Hong Kong auteur Johnnie To — which dares to stick its middle finger directly in the face of a government taking itself to any end in hopes of earning the statistical victory, no matter how body-strewn it all may prove.

The audacity of his gesture is palpable, at times throbbing; a shame, then, that To’s characterizations barely exceed a sketch. In spite of how often Drug War finds itself thriving on the juncture of tropes — the narrative staples of an undercover story and its larger, more relevant social criticism finding nice spaces of common interest — the propulsive accumulation of incidents and intrigue eventually crosses a threshold from which, it becomes clear, no tangible person-to-person conflict will ever fully emerge. These are thrills of the most ephemeral brand: it need not be demanded that complex psychological profiles play into the action — nor, even, a distinctive and readily identifiable cast of characters; the morally conflicted mass typically proves sufficient — but by the time we reach a grand finale of bullets and hurt feelings, the misfired shot at pathos is as elemental to the lack of a complete story as it is the sign of questionable direction.

If only on the page, for To brings with him exertions of formal austerity seemingly alien to this type of picture in the first place: Drug War’s screed against the governmental policies locking humans into single trajectories — concepts of oppression, natch — isn’t summoned to reality by dialogue, but rigid visual structure. His cinema does not allow for a routine talk between secret-carrying men in back rooms; though these moments ring with little of note in the way they’re scripted and spoken, as translated through shots and edits they’re terse, claustrophobic exchanges clearly, keenly attuned to the perilous nature of illegal negotiation. But for all his high-minded concerns with corruption, To, thankfully, isn’t afraid to have spots of fun; the domineering visual motif of street-locked surveillance cameras can be readily matched by touches of a purely enjoyable shade — more notably a shifting cigarette holder containing a secret camera, or even a long-span visual rhyme that pays off with a well-played pee joke.

But To’s script rears its head yet again, in its quieter moments (or the closest thing Drug War has to a “quiet moment”) peeling apart as the tension between cops and dealers proves dramatically untenable unless painted in broad strokes. Naturally, then, proceedings glide along at their smoothest pace when playing like so during the initial moments, To’s mélange of corruption making way to fall right in. (It must have been north of ten minutes before a character’s name is so much as spoken, and it’s longer before we’re fully let on as to who the picture’s central protagonist would even be.) This is a genuine pleasure to luxuriate in, which only renders the narrowing of focus — in its own sense the ultimate signal of narrow focus itself — all the more disappointing.

Perhaps beggars can’t be choosers: Save for an out-of-place pair of invincible mute twins — they’d feel more at home in, say, Smokin’ Aces, from which Drug War has markedly different aspiration — the film’s conclusion is a bullet-riddled, thrillingly shot, edited, and scored (sound design is loud, impactful, brutal) piece of work that puts most modern action staging to shame, yet the matter of who actually lives and who actually dies therein is nearly irrelevant. No matter their fine application, the character beats To litters throughout — e.g. the use of handcuffs in the final exchange of fire; the morbid initial location of action; a brutal “reprimand” as final grace note — come after 95 minutes of diminishing returns, finally registering as noise overlaying noise and effect without consequence.

Although those who count themselves among the legion of Johnnie To devotees will likely find more of value in Drug War‘s frantic construction, this newcomer was left alternately thrilled and cold to mildly satisfying ends. Might all its peculiarities click more efficiently after exploring his large, ever-ballooning filmography? I can’t say the desire to learn has been snuffed out by this brief encounter.

Drug War shows tonight at New York Asian Film Festival and will enter limited theatrical release on July 26.