Editor’s Note: This is the first in a new feature series titled Adapt This, an in-depth look at a specific film adaptation and its original source novel. If you like this one and have any future ideas, please send them our way at editors (at) thefilmstage.com. Read on!

We all love movies. I know Dane Cook pointed it out more recently than, say, Luis Buñuel, but we all love cinematic adventures. Movies are, in the words of Susan Sarandon, the keepers of our dreams. We go to sporting events or political rallies and have a shared experience, but only movies can crowd a herd of us noisy, smelly humans into a dark room, sit us down, and shut us up by projecting someone else’s dreams for two hours.

What we tend to forgot is how often these movies are based on these things called books. Hold on, don’t go! I know you want to click over to OMG! on Yahoo! but stay with me for a while longer while we discuss the pros and cons of the cinematic adaptation of a previously published material. I’ll begin with something recent, co-writer and director Ben Affleck‘s adaptation of crime novelist Chuck Hogan‘s Prince of Thieves, which Affleck astutely retitled The Town. If you haven’t seen the film or read the book, be warned: this article will have MASSIVE SPOILERS. You’ve been warned. Here we go.

The movie The Town is a tense, exciting chronicle of modern-day Boston thieves, tracked obsessively by their FBI counterparts. Ben Affleck leads the way as Doug MacCray, raised in Charlestown, a neighborhood which, as in the Chuck Hogan novel (and evidently, real life), is a breeding ground for bank and armored car robbers, dope runners, bookies, and damn near any other criminal element you can think of. Doug was raised by his jailbird daddy, Stephen “Big Mac” MacCray, who as the story opens is serving a long stretch in Walpole State Penitentiary for armed robbery. Having washed out of pro hockey – he was a bid deal with the Boston Bruins for a split second – Doug returned to the Town and settled into a life of crime, planning heists which gradually became big enough to need a crew. His best friend and right hand is the violent, unpredictable sociopath Jem (Jeremy Renner, nailing the role and stealing every scene he’s in). After the opening back robbery, Jem decides to take the bank manager, Claire Keesey (Rebecca Hall) hostage and as Doug checks up on her after the job, he finds himself falling for her.

The movie The Town is a tense, exciting chronicle of modern-day Boston thieves, tracked obsessively by their FBI counterparts. Ben Affleck leads the way as Doug MacCray, raised in Charlestown, a neighborhood which, as in the Chuck Hogan novel (and evidently, real life), is a breeding ground for bank and armored car robbers, dope runners, bookies, and damn near any other criminal element you can think of. Doug was raised by his jailbird daddy, Stephen “Big Mac” MacCray, who as the story opens is serving a long stretch in Walpole State Penitentiary for armed robbery. Having washed out of pro hockey – he was a bid deal with the Boston Bruins for a split second – Doug returned to the Town and settled into a life of crime, planning heists which gradually became big enough to need a crew. His best friend and right hand is the violent, unpredictable sociopath Jem (Jeremy Renner, nailing the role and stealing every scene he’s in). After the opening back robbery, Jem decides to take the bank manager, Claire Keesey (Rebecca Hall) hostage and as Doug checks up on her after the job, he finds himself falling for her.

This outline and the general sketch of the film are surprisingly close to the source material – except for the time-frame of book, which is set in 1994. Affleck and co-writers Peter Craig and Aaron Stockard clearly have a great deal of respect for Hogan’s structure. That’s not a surprise: Chuck Hogan is among the nation’s premiere writers of crime fiction (Prince of Thieves was hailed by many critics and authors – including Stephen King – as one of the best novels of 2004), and his recent vampire-plague novels co-authored with no less a worthy than Guillermo Del Toro (The Strain Trilogy, which encompasses The Strain, The Fall, and The Night Eternal, the last of which will appear in October 2011) are some remarkable pieces of fiction.

Affleck’s choice of material reflects a depth and maturity toward his directing projects which rarely reflect his choice of acting gigs (Reindeer Games, Paycheck, The Sum of All Fears, anyone?). His directing debut was the underrated Gone Baby Gone, another Boston-set crime story, based on Shutter Island author Dennis Lehane‘s novel. His sophomore effort is far more crowd-pleasing, but no less interesting. Word ’round the campfire is Affleck’s first cut of The Town was over four hours long, and nearly mirrored the novel.

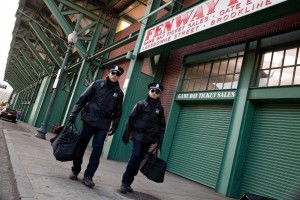

I’d like to see that movie. As it stands, Affleck’s film is a combination of fascinating procedural, exciting crime movie and satisfying character study. Still, Hogan’s novel plumbs depths of these characters that the movie never has time to touch on. Like in the book, there are three major heists, and like in the book, the first and third are a bank and Fenway Park, respectively. Let’s focus on the massive detours from the Hogan’s novel, which illustrate both astute and intelligent adaptation and unfortunate neglect of character.

Affleck, a filmmaker and movie star – oh, and Academy Award-winning screenwriter for Good Will Hunting – knows that in movies, three is the golden number. If you went to film school or has a friend who went to film school or knows photography, “The Rule of Threes” will sometimes drive you crazy. I went to film school myself (and mock me if you have to, it’s okay, I understand), and my greatest directing teacher – a veteran of television, with credits on shows like Life Goes On, Monk, the SyFy Battlestar: Galactica and Terminator: The Sarah Connor Chronicles – once told us that three is the magic number for “this stuff,” meaning our directing exercises. It also applies directly to storytelling at large, as any frustrated writer desperate to boil their story into Three Acts certainly knows. Aristotle said it quite simply in his Poetics: stories have a beginning, a middle and an end. And you can start anywhere.

Okay, so the number three works. Many heist movies have one major heist with a lot of little cons and such (I’m looking at you, David Mamet‘s Heist – a good movie that had one goddam heist, not counting the opening scene which was an opening scene, dammit), but Ben Affleck – and Chuck Hogan before him – wisely gave the world three terrific sequences of thievery, and damned if they weren’t well done.

This is where Affleck improves on the source material. The opening of the novel has Doug and his crew already inside the bank, having a cut a hole through the dentist’s office above the bank office during the long weekend before. It’s actually a terrific intro to the crew we’ll come to know – once inside, they spend their time bullshitting with each other and snacking on the floor, like juvenile delinquents behind a drug store they just shoplifted. Hogan also secures his knowledge of Boston: in such an old city, it’s common for businesses to share close quarters. The movie begins with Doug’s crew casing the bank and charging in when an armored car stops to make a pickup. Affleck knows an audience likes to be on the same level of the action in a crime movie… for the most part. He lets us know more – or less – as the scene requires. Movies like this engage us with their procedure. Doug’s opening narration puts us in the minds of these thieves – we know their targets, we know the situation.

This is where Affleck improves on the source material. The opening of the novel has Doug and his crew already inside the bank, having a cut a hole through the dentist’s office above the bank office during the long weekend before. It’s actually a terrific intro to the crew we’ll come to know – once inside, they spend their time bullshitting with each other and snacking on the floor, like juvenile delinquents behind a drug store they just shoplifted. Hogan also secures his knowledge of Boston: in such an old city, it’s common for businesses to share close quarters. The movie begins with Doug’s crew casing the bank and charging in when an armored car stops to make a pickup. Affleck knows an audience likes to be on the same level of the action in a crime movie… for the most part. He lets us know more – or less – as the scene requires. Movies like this engage us with their procedure. Doug’s opening narration puts us in the minds of these thieves – we know their targets, we know the situation.

The middle heist is the movie’s biggest departure from the novel. In the book, Doug cases a suburban movie theater, which his crew robs after a big weekend… can you guess why it was changed? I suspect even the very first draft of the script never included the movie theater job. I’ve never seen one in a movie… and never will. I doubt any studio – or theater chain – would want their patrons sitting there in the dark and suddenly wondering if they’re about to held up at gunpoint. Think about it: are you ever quite as vulnerable as in a dark movie theater, staring slack-jawed at giant transforming robots pounding the living shit out of downtown L.A.?

The movie version replaced this multiplex robbery with a streamlined armored-car job, followed by a superior car chase sequence. The aftermath of all this allows Affleck a further departure: the tried and true meeting of Protagonist and Antagonist – namely, Affleck’s Dough MacRay and the absolutely terrific Jon Hamm’s FBI Special Agent Adam Frawley. In the book, MacCray and Frawley are never in the same room until the very, very end. In The Town, Affleck wisely ditches that concept. Doug is arrested after the armored car gig and hauled into an interrogation room. Frawley walks in, and they let it rip – their nose-to-nose scene is one of the movie’s best, and belongs on a shortlist of Greatest Interrogation Scenes Ever Filmed (in case you’re keeping score, The Dark Knight belongs on that list, along with Mystic River, Se7en and L.A. Confidential).

Chuck Hogan never allows these characters to directly interact in the novel, but there are plenty of close shaves. One particularly entertaining sequence in Prince of Thieves finds Frawley – who in the book is much more of a rival for Claire’s affections – finds a garage Dougie keeps hidden. He breaks in, looking for damning evidence but only finds Doug’s gorgeous, classic Corvette, restored from the ground up. Frawley carefully, viciously keys the living shit out of it.

Chuck Hogan never allows these characters to directly interact in the novel, but there are plenty of close shaves. One particularly entertaining sequence in Prince of Thieves finds Frawley – who in the book is much more of a rival for Claire’s affections – finds a garage Dougie keeps hidden. He breaks in, looking for damning evidence but only finds Doug’s gorgeous, classic Corvette, restored from the ground up. Frawley carefully, viciously keys the living shit out of it.

Yet, while Affleck lets these two opposing forces go head to head regarding the heists, he dials back the novel’s major subplot, a love triangle between Frawley, Claire and Doug. In the book, Frawley is quite aggressively after her, even taking her out a few times. Doug pursues her relentlessly, having built her up as his bright, shining hope of a normal life. Most of this is glossed over in the film, for better and worse. The strained relationship between Doug and the psycho-pitbull Jem is thrust into the center, and Frawley’s designs on Claire are only hinted at.

Claire is somewhat vapid and completely indecisive in the book, shying away from both Doug and Frawley. She’s far more likable in the film, which makes sense, especially given the attention Affleck puts on their courtship. The one character who is almost completely shoved into the shadows is Desmond Elden, played well by Owen Burke. Des is the techie who makes their opening heist possible, and in the book he’s given a full, sad life. His father was gunned down when he was a boy – commonly believed at the hands of Fergie the Florist (the late, great Pete Postlethwaite). Doug befriends Des, whose life is a constant reminder to Doug of what the Town is: a black hole no one escapes for long.

The novel’s far-darker ending is completely different in the film. In the book, Doug survives his shootout with Fergie after the Fenway heist (which is almost exactly the same as in the film), but shows up on Claire’s doorstep, shot full of holes. His dying image is of Claire hovering over him and Frawley just behind her. Claire is horrified less by Doug’s death than his choice to die near her. The film’s more hopeful ending is the likely product of focus groups and a studio preference for open-ended sequel bait.

The novel’s far-darker ending is completely different in the film. In the book, Doug survives his shootout with Fergie after the Fenway heist (which is almost exactly the same as in the film), but shows up on Claire’s doorstep, shot full of holes. His dying image is of Claire hovering over him and Frawley just behind her. Claire is horrified less by Doug’s death than his choice to die near her. The film’s more hopeful ending is the likely product of focus groups and a studio preference for open-ended sequel bait.

The film’s ending can be considered a “happy” one, but Affleck wisely lets the audience wonder if Claire and Doug end up together, and if Frawley ever gives up his quest for MacCray. A sequel is conceivable, but it would betray the tragic spirit of Hogan’s book. The movie version of Doug MacCray learns that there is a way out, and he chooses a different path. In the book, MacCray turns his back on his AA-fueled sobriety and downs a six-pack of Miller High Life just before the Fenway robbery, a symbolic return to the Town, acceptance of his father’s legacy, and acknowledging his own doom. Affleck gave us something more hopeful and uplifting… but less honest.

I hope the world sees Ben Affleck’s director’s cut of The Town. If it’s as faithful as I’ve heard it is, the full film may just be a modern crime-film masterpiece, on the level of John Huston‘s The Asphalt Jungle or Scorsese‘s GoodFellas. As is, The Town is a fine film, but Chuck Hogan’s Prince of Thieves contains hard, sobering lessons that the crowd-pleasing movie sidesteps. Check out Hogan’s book, it’s a knockout.

Were you a fan of Affleck’s adaptation? What about the original novel?