When Yeon Sang-ho was conceiving his new film Peninsula, the much-anticipated follow-up to his surprise 2016 hit zombie action film Train to Busan, there was no way of knowing that audiences would be watching it during an outbreak and societal breakdown of their own in the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Regardless, it’s difficult to dissociate many of its imagined extinction anxieties, quarantine paranoia, and various precarious systems of control being shattered from our very real ones.

Which is not to say that making us consider our own world and political landscape is something new for the zombie genre—George Romero’s towering Night of the Living Dead is one of the most ferocious, unflinching depictions of the American psyche in the heat of the Vietnam War and Civil Rights movement, and subsequent sequels would further investigate corporate and military power under the guise of horror thrills—but there is a new, strange sort of distance that comes with watching another derivative entry in this genre that has made the imagined apocalypse we’ve escaped to many times before feel much smaller.

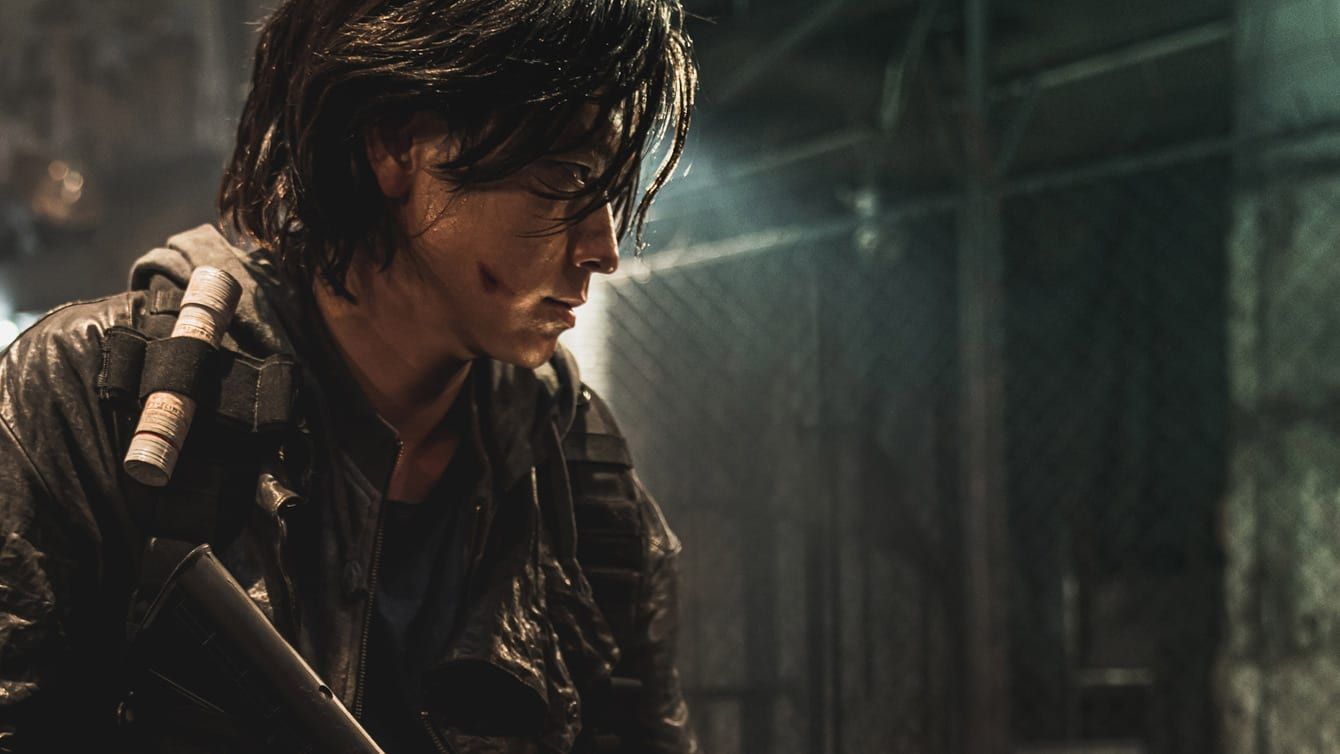

Which is unfortunate for Peninsula, an all-around competently made zombie actioner with all the mechanically calibrated setpieces and broad emotional moments fans of the first will expect: a cowardly lead who learns to be more selfless, a psychotic leader who weaponizes fear of other survivors, and various friends, family members, and precocious kids who get caught up in collateral damage as they all navigate the given dystopian disaster situation in hopes of securing an uncertain future at best.

What’s frustrating about Yeon Sang-ho’s sequel is that it’s the exact kind of film that was already pretty tired before Zack Snyder’s Dawn of the Dead remake came out in 2004—only a few years later The Walking Dead would become a massive hit for AMC and Romero would retire from the genre altogether both due to its overexposure in pop culture and because he couldn’t pitch a small, social commentary zombie movie anymore. To get one made they needed to be American action blockbusters now like World War Z and he wasn’t interested.

What made Train to Busan work despite its action movie sensibilities that weren’t altogether dissimilar from World War Z, was the intimacy of its train concept both in terms of its easy access to an array of personalities all connected by an everyday commute (which also gave it subtle commentaries on class, specific national politics, and social breakdowns––all things Romero loved exploring) but also the logistics and movement of the action when ground zero of the apocalypse eventually gets started in the first reel.

The sheer speed and volume of the zombie hordes smashing up against spaces that are also on the move gave the action a genuine sense of momentum and there’s a section in that film where the characters are just strategically moving from a cart near the back to a cart near the front (not unlike Bong Joon-ho’s sci-fi train actioner Snowpiercer), they are using geography, lighting, sound, and their own bodies as tools for the action where an American zombie film would’ve just had them pull out some guns.

It was still technically a simple action/horror hybrid with a few blockbusters aspirations but it was cleverly conceived and restrained by its premise. The basic propulsion of its concept overpowered any gripes one might have with its writing and the stock characterizations (workaholic dad learns to be more present, cartoonishly selfish capitalist, doomed teen lovers, etc.) that had clear-cut arcs and big emotional moments you could predict within a few seconds of them being introduced.

The same can not be said of Peninsula, which maintains much of the broad, mechanical genre writing but replaces the uniquely contained train setting with a vague, dilapidated quarantine zone overrun with paramilitary gangs and civilian survivors hunting for scraps that you’ve seen dozens of times in other zombie infection movies (most recently in video game form in The Last of Us Part II) and action scenes that instead of tracing the clever, minute logistics of movement in a unique space is now relegated mostly to John Wick-style gunplay during zombie horde rushes or Fast & Furious-esque CG car chases with CG bodies being run over. This maybe should’ve been expected considering the American title, featuring Train to Busan Presents, but it doesn’t pull off these sequences better than the franchises it is cribbing from.

Peninsula still holds a number of pleasures; the thrust of the plotting involves desperate mercenaries performing a heist inside a warzone (in the early scenes it briefly appeared like this was going to be a Kelly’s Heroes take on the zombie movie, which is all I’ll be thinking about for a few weeks now), as well as a zombie sport/gladiator coliseum that looks like it could belong in a Mad Max or Conan the Barbarian movie. By the time it reaches its broad, emotionally manipulative finale, it does have some refreshingly optimistic ideas about small, sacrificial gestures making a difference and that choosing emotion over logic while dooming us in other zombie movies is also what makes humanity worth saving in the first place. It’s just unfortunate that Yeon Sang-ho couldn’t conceive any of these neat designs or ideas in the same lean, clever visual style of his original and instead indulges in the derivative, American blockbuster spectacle we were all glad the first one wasn’t.

Train to Busan Presents: Peninsula opens in theaters on August 21.