Most of cinema’s best films are those that do rather than explain. These works are created by artists wielding airtight concepts insofar as attaining their goal of delivering a specific, emotion-fueled message. Kenyan creative Mbithi Masya‘s feature debut Kati Kati is a perfect example of what can be made when the right resources are supplied to the right people. Tom Tykwer, Marie Stenmann-Tykwer, and their One Fine Day shingle (originally formed to facilitate year-round artistic opportunities for children in Nairobi) helped with the former while Masya, co-writer Mugambi Nthiga, and his cast/crew brought the latter with their stirring look into the soul by way of purgatorial limbo. We don’t know how they got here or what comes next, but we do quickly understand the thing keeping them: guilt.

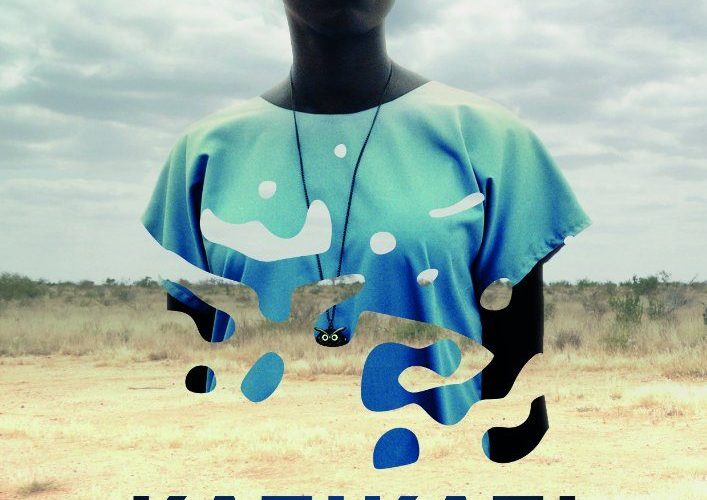

You know you’re in for something special from the opening of African expanse containing Kaleche (Nyokabi Gethaiga) in the distance at the center of the screen. She doesn’t know where she is, who she is, or what to do. So she just walks until finding shelter where voices can be heard past the deserted lobby with activity schedules and resident names. Those who live here are playing charades and having a wonderful time until Kaleche approaches from behind the current participant. Finally she speaks, asking what this place is as the rest stare back in knowing comprehension. Thoma (Elsaphan Njora) rises and says they are in Kati Kati, the reason being that they are all dead. Someone jokes she’s going to be a runner and off she goes.

It’s a brilliant introduction that provides everything we need to prepare for what’s coming. If she has arrived, someone must have left. But instead of letting our minds race to figure out the game, everyone begins to talk and explain what they already know. Thoma has been here for three years, Mikey (Paul Ogola) six months despite passing in 1996. Why did it take him so long to arrive? Where was he between then and now? Why can they all remember these details and yet Kaleche has amnesia? Well, while these questions excite, it’s implicitly revealed that they don’t necessarily matter. What happened then and what’s to come are unimportant when faced with the profound internal conflict of today. Knowing your fate is vastly different than accepting it.

Masya is masterful with economy, using nothing but white paint to signify an aberration in the status quo. Seeing it for the first time is jarring on King’s (Peter King Mwania) hands as he stops Kaleche from hurting herself, but perhaps even more intense when we see Thoma talking to a version of himself covered in it. Characters start to reveal handprints, an aftereffect of experiencing visions from the past haunting them day and night. Everyone here is already dead and yet they each fear these specters and what their appearance may ultimately signify. They arrive in greater numbers once Kaleche joins them with her inquisitive mind and suddenly these lost refugees who’ve only witnessed two people leave watch as two more go in a matter of days.

These hauntings are heartbreaking in their emotional reunions, devastating as the truth of the deaths of some characters met are explained. The idea that to leave means to “give in” is bandied about, but this is a lie manifested by anxiety. The goal should be to leave, no matter how much fun can be had by the pool. Kati Kati isn’t Heaven and it isn’t Hell—it isn’t a destination at all. Something happened in the darkness of death to earn them a place here, but that is merely the first step. Reforming a physical body with the capacity to remember supplies them the means to face what it is they’ve done. This prison’s wrought because they cannot live with those yet unknown actions. That shame is unyielding.

We see frustration from those who’ve been trapped for so long watching newer members evaporate, angry they haven’t found escape. Voices tell them they aren’t worthy of such release and perhaps they aren’t. Some see those they have wronged or believe they have despite knowing there was nothing they could have done to stop whatever tragedy occurred—ghosts providing someone to combat beyond their own consciences. “Giving in” to these visions isn’t therefore admitting defeat. On the contrary, it’s forgiving one’s self enough to absolve them of their sins (earned or not). By acknowledging the deed, accepting your role removed from any excuses, you can finally quiet the guilt-driven voice keeping you awake at night. “Giving in” isn’t breathing life into a lie; it’s conceding the truth.

How the process affects Kaleche and Thoma, however, is much less straightforward than the rest. There are secrets hidden from sight where these two are concerned—her blank memory and his fractured mind creating an adversary from his refusal to provide closure to the person he wronged. We never find out why it takes so long for some to arrive at Kati Kati, but with one character we discover the necessity for staying in perpetuity. Even though the need is self-forgiveness, the process is hardly a solitary one. Guilt must be experienced, the pain and suffering of what was done avenged by punishment no amount of “amending your life” can attempt to overcome. Prayers are just words; penance a means to remember your actions not to expunge them.

There’s so many subtle details placed throughout that highlighting one would inevitably trigger a cycle of hypothetical meanings once they appear in context. It’s so much better to understand in hindsight, hearing a character admit what they did aloud and remembering a habit of theirs for what it is underneath the person they’ve become in death. Those I can speak about are world-building attributes like disappearing food at mealtime’s completion or how anything you ask for on a pad of paper will arrive at your doorstep the next morning. Who’s responsible? God? Angels? Satan? Again, it doesn’t matter. Masya is simply bolstering this setting with depth and authenticity so we don’t waste time questioning its construction. It’s the characters and their personal torture that matter, not the place.

Kati Kati premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival.