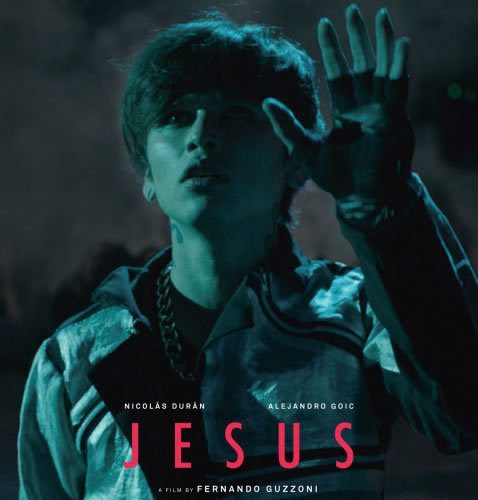

Adolescent hijinks turn tragic on multiple fronts in Fernando Guzzoni‘s Jesús despite my not being sure there was going to be a solid point to the film until mid-way through. Everything previous merely sat as a slice of life for the titular character, a normal everyday Chilean punk named Jesús (Nicolás Durán) with too much autonomy and not enough direction. He’s practically raising himself after the death of his mother, Dad (Alejandro Goic‘s Héctor) constantly out of town working. So the eighteen-year old roams the streets dancing with a Korean Pop band for kicks, breaking into parks at night to drink and do whippits, or cruising for girls at parties to earn a blowjob. He means well most times, but his malleability when drunk inevitably spells trouble.

And it’s a good thing trouble comes — not for him, but the audience. Before then the only real action occurs off-screen, a supposed mugging taking Jesús’ glasses and phone in one fell swoop. Besides that it’s just him getting wasted with Pizarro (Sebastián Ayala) and Beto (Gastón Salgado), two miscreants for which the lengths they’ll go to have a good time are yet to be determined. Héctor arrives briefly as a caring man with a firm hand, giving his son money to buy new glasses if he agrees to start pulling his weight around the house. If Jesús isn’t finishing high school until next semester, he can at least cleanup after himself. Rather than this chore proving a matter of appeasing his father, though, it’s really about self-pride.

Their relationship can’t be anything other than strained as a result. Héctor is doing his best, but remaining out of sight to do so. Conversations revolve around what’s on TV because anytime Jesús tries to talk about his life it gets shot down by prejudice. His father would rather poke fun at the people he hangs with instead of making an effort to meet them or engage his son in anything other than chastisement. I’m not saying we’re supposed to blame the old man for his offspring’s actions to come, but the heavy air between them definitely doesn’t help. Jesús’ environment is what pushes him into precarious situations fueled by sex and drugs. It’s not an excuse as his guilt ravaged self-loathing attests, but it is a cause.

The saddest part proves to be the simple revelation that it takes a grave misstep to finally get Héctor to stop and listen — the definition of too late. He checks his phone to see work calling, but doesn’t pick up. He’s in parent mode, racking his brain to find a solution to an impossible situation so as not to think about Jesús’ actions on an objective level. There’s no one else who can help the kid, his friends and accomplices turning on his sensitivity and humanity as they go into full alert for self-preservation. But what is Héctor to do when the worst possible scenario is revealed to have come true? What can any parent do when justice condemns a child while saving the latter forsakes an innocent?

Guzzoni turns his intensely authentic look at teenage rebellion with unsimulated oral sex, rampant drug use, and gleeful violence into a dark parable pitting blood relations against God. From the grainy pulse of a K-Pop competition to inebriated laughter to fellatio under a tree memorializing the dead, Jesús’ journey is a roller coaster without rules or consequences that he has yet seen. They run wild and scorch earth, their drunken stupors making fools of themselves more than anything else. We applaud Héctor’s tough love; resigned to the reality it’s proving ineffective. And we watch Jesús’ seemingly compassionate teen fall in with a crowd devoid of morality. Guzzoni won’t even let a potential good deed lie, turning an unsuspecting stranger’s salvation into a nightmare for all involved instead.

There’s no benefit of the doubt or optimistic resolution, every opportunity Jesús and Héctor take to hopefully make the horrible situation better blows up in their faces. What seemed like harmless fun turns cruel quickly and just as Jesús was left mugged and beaten while onlookers did nothing to help, he lets the adrenaline rush of friendship and the immortality of beer goggles turn the tables so he becomes worse than the scared public communally rejoicing in silence that they weren’t on the other end of the knife. Jesús becomes a willing participant this instance. A cheerleader and accomplice to a heinous act that may or may not come back to haunt him. But it’s often the prison we erect in our minds that’s worse than jail.

A point of view shift occurs as Jesús succumbs to his pain. Guzzoni supplies a reprieve from feeling sorry for him despite his crime to linger on Héctor instead. We’ve done it before with camera in car as he shoves his son out and drives away, but now he becomes the focal point. We’re privy to his emotions, his pain and suffering while wrestling with personal demons about what to do next. He wants to help his child, of course he does. But at what cost to himself? Can he live with being an accomplice to the accomplice? How about watching his son be taken away in handcuffs? How removed from the act must he be to not feel complicit? Because even if he wasn’t there, knowing’s enough.

The raw aesthetic of Jesús’ life when he truly believed he was invincible is multiplied ten-fold by emotional turmoil as the bottom drops while Héctor’s frustrations melt into uncertain worry, the struggle between humanity and family too much to bear. Both Durán and Goic are phenomenal in the roles, their feelings pent-up until tearful releases shown in almost complete silence arrive in the distance. Guzzoni shows us reactions first, the distraught soul on the other end left to our imagination until entering into frame. And with a bleak finale that won’t soon leave you, Jesús proves a gripping cautionary tale unafraid to let its characters suffer for justice. A son’s mistake becomes a father’s failure and no matter what happens, no one’s soul is left whole.

Jesús is now playing at the Toronto International Film Festival.