An African man—a hopeful immigrant—says something very interesting to his prospective lawyer Michael (Jakub Gierszal) at the start of Urszula Antoniak’s Beyond Words. When asked if he has a better excuse for finding refuge in Germany than the simple desire to choose his own home as a free human being, he says, “No.” He states that he doesn’t need one. It’s an argument that’s been raging here in America since the 2016 presidential campaign began, this idea that a country can turn you away on a whim or a technicality in whatever way it sees fit to discriminate or “cleanse” itself. And Michael understands why. He embraces it. The reason? Because he didn’t need a better excuse when he immigrated. He fit right in.

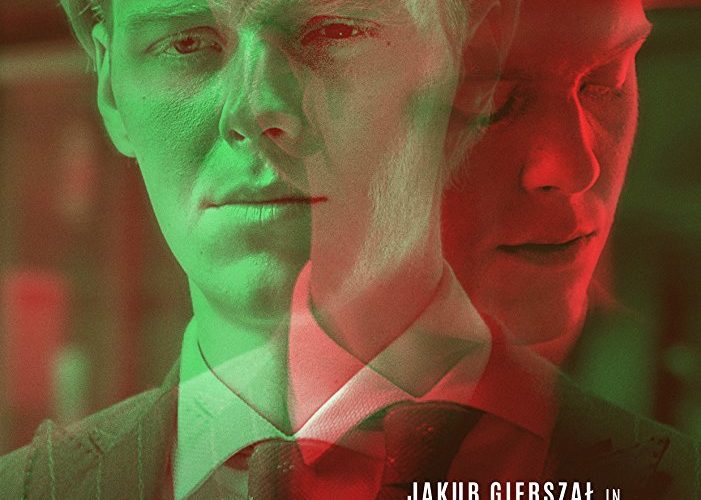

In his quest for the freedom to be successful, Michael only had to apply for a job. He’s white with blonde hair and he speaks the language fluently. There was more opportunity to become an in-demand lawyer in Germany as opposed to Poland and frankly there wasn’t anything keeping him in his homeland anymore to sabotage those aspirations. What he did that perhaps many others wouldn’t, however, is become German. We’re not talking citizenship either. He underwent a complete transformation to the point of doing all he could to expunge any remnant of his heritage—not as a means to hide, but to move forward. Michael didn’t want people to look at him like he looked at this African poet. He refused to be seen as an outsider.

And he was rewarded for it: the fancy apartment, the clichéd perks of affluence, and an easy friendship/rapport with his boss Frantz (Christian Löber). They were set to takeover the world until Michael is reminded of everything he hoped to forget with the appearance of his long-thought dead father Stanislaw (Andrzej Chyra). Even though Michael’s the one who reached out (albeit years ago), the simple sound of Polish again leaving his mouth creates a fracture in his identity. Suddenly he has found himself as the “other.” He needs to translate with those he so confidently spoke with days before. There’s an inherent embarrassment to his actions not because his father may not fit into this posh new life, but because he is reminded that he might not himself.

The film is literally just a weekend visit wherein Michael can maybe get to know this man he thought was dead and yet so many profound questions crop up as a result. We begin to understand the as-yet odd vignettes following a waitress (Justyna Wasilewska’s Alina) at a cafe Michael frequents. We start to watch as Stanislaw becomes as uncomfortable as his son for the opposite reasons. And this notion that Michael’s life has been a ruse can’t stop itself from rising to the surface since those who know him best know the truth. What does it say to them that you can so easily shed this part of yourself to become steeped in a history tainted by horrors committed on the country in which you were born?

Antoniak presents Michael as another rich kid making money off the backs of the less fortunate only to slowly peel away this façade and expose the complex machinations that drove him to manufacture it. He quickly becomes an outlier, one compared to other characters that are nothing if not honest about what they are to a fault (a truth perfectly encapsulated with a lunch where Stanislaw and Frantz allow their biting humor to escape only to have Michael sanitize their words in false translations). Even when face-to-face with the man who provided half his genetic code, he still does everything possible to divert the conversation. Michael has an origin that he tells himself, one that the smallest crack can derail and unravel the persona he so desperately wields.

This is the difference between Michael and that African poet. They both confidently present themselves as men with nothing to hide, but one built that confidence on a fabrication. Michael didn’t lie to cross borders; he forsook his heritage to remain. Rather than freedom, that could be construed as cowardice. African refugees can’t hide their color or accents and yet they arrive in Germany and create a life regardless. Why couldn’t he? Why can’t he even bring himself to admit feelings for a woman he cares for simply because she is a window to the past he deems a liability? Why can he allow himself to embrace it when having fun with his father and yet instantly stop when moving from a private setting to a public one?

Michael becomes torn apart and utterly lost. His father and Frantz see through the artifice from contrasting positions and can’t hide that they do. As such Michael can no longer lie to himself that he’s one above the other or reconcile both for them to co-exist. And when those two worlds collide, he inevitably must confront a breaking point wherein he might lose everything. Antoniak could have presented this existential nightmare many ways, but she chooses to have him go somewhere that he truly cannot fit in as Pole or German. Just as Stanislaw says around halfway through, he and his son are “all or nothing” guys. So, to figure out who he is, Michael must force himself to experience what it’s like to have no control.

Beyond Words proves a nuanced drama about what it means to exist in a world that finds itself so connected and yet further apart than ever before. Antoniak shows how easy it is for some to adapt in this day and age and how that ease only augments prejudice and superiority over those who cannot. She’s providing an example of that insidious power struggle we all combat to survive at others’ expense—how we will embrace our enemy and sacrifice a part of ourselves if it means retaining control somewhere else. Michael will become German because it gives him more than what being Polish provides. White women vote for Trump because he affords them power as a race that the opposition couldn’t as a gender. Survival is always self-serving.

Beyond Words premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival.