Lise (Flora Ofelia Hofmann Lindahl) couldn’t be happier now that she knows her mother’s (Ida Cæcilie Rasmussen’s Anna) determination has successfully overcome her father’s (Thure Lindhardt’s Anders) objections about sending her to school. It’s the late 1800s after all. A big reason why a farming family such as theirs has so many children is to work the land. Sending off the eldest at fourteen isn’t therefore conducive to their home’s machinery—especially since Anders has no qualms with leaving the daily chores to his sister, mother, daughters, and servants while leaving for hours on end. If Lise had anyone else to thank besides her mother for the miracle that is her impending emancipation, it would therefore have to be God. Unfortunately, God’s will has never been purely optimistic.

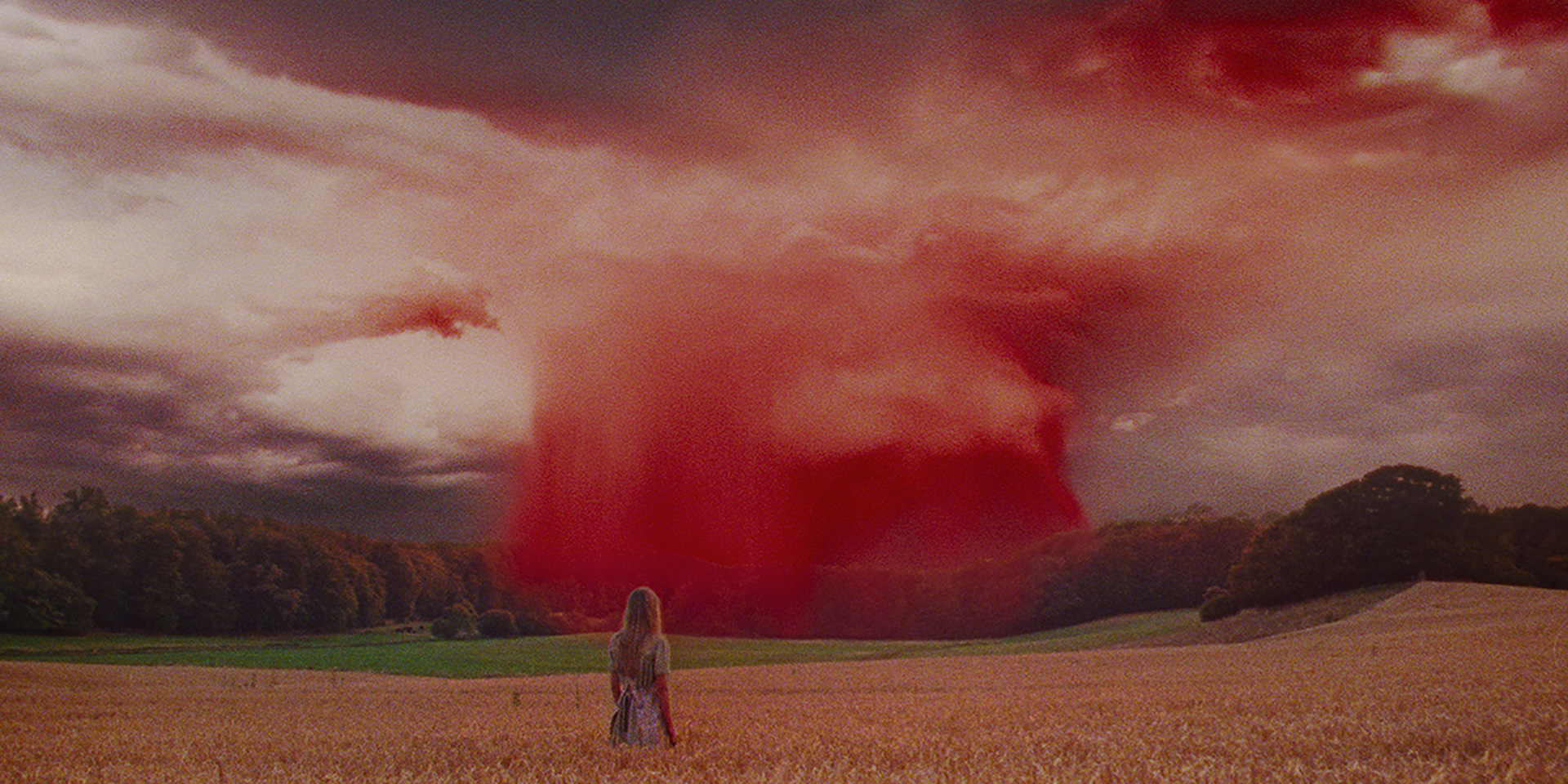

Based on the 1912 novel by Danish author Marie Bregendahl, writer/director Tea Lindeburg’s feature debut Du som er i himlen [As in Heaven] witnesses a twenty-four-hour period that will forever change its protagonist’s life. Lise awakens from a dream walking through a gorgeous field under an immaculate sky believing she has nothing to worry about anymore, but we know different. We remember the storm cloud that forms above her and the blood-red rain pouring down upon her face even if she might dismiss them. Her cheery disposition and welcome visit with her mother in the kitchen are merely the calm sense of hope about to be upended by a not-yet-visible lesson by God’s hand. Lise borrows her mother’s silver hairclip with promise and returns with sorrow.

First, it’s her father demanding she be useful while still under his roof. Then it’s young Kristian (Emil Hornemann Juel)—a boy her age, left by his father to work the land for its new owners—projecting his pain onto her via a vile ultimatum. And then it’s the boy her mother took in as a child (Albert Rudbeck Lindhardt’s Jens Peter) flirting with her in the barn only to help her lose that barrette in the hay. Lise is shamed for wanting education, objectified for being a woman, and, in her mind, punished for her lust. It’s like God is reminding her who really gave her everything her heart desired by forcing her to realize it all came at a price too high for earthly assurances.

That’s when the screams begin. Anna had her own dream portending a difficult labor culminating in the birth of a boy. To dare mix religion with superstition is to find yourself at the mercy of dumb luck since intelligence plays no role in either. The midwife begs to send for the doctor when the blood starts pouring, but Klog Sine (Kirsten Olesen) and Anders’ mother refuse to comply due to that premonition. What we didn’t know initially is that Anna was also warned of a doctor’s presence guaranteeing death. She doesn’t want to leave her children motherless (Kristian is evidence of what happens if someone like her doesn’t take them in) and her labor proving difficult means they must presume all other details will come true too.

Lise and her eldest cousin Elsbet (Palma Lindeburg Leth) are thus caught in a sort of suspended state of animation. They aren’t young enough to go to their grandmother’s house and sleep like the other kids, but they’re also not quite old enough to fully grasp what they’re witnessing once Anna is seen in her red-soaked gown howling with pain. It’s enough to scare them into never wanting children of their own just as it forces them to process the reality that she may not make it through the night. The longer they wait to get the doctor, the less likely it is she survives. His presence might have saved her at the beginning, but a last-ditch attempt towards the end merely renders Anna’s dream a self-fulfilling prophecy.

And now the rain from Lise’s dream can no longer be forgotten. Talk of giving one’s emotions over to God’s will fractures characters’ thoughts into two camps. There’s either reason behind Anna’s potential death or her demise will ultimately prove God doesn’t exist. To be faced with those extremes after being brought up in the church can’t be easy, but what else is Lise to think? Either they are all doomed to Hell (Lindeburg delivers an unforgettable image of Anna burning alive in her bed) with no one to save them or this death becomes proof that Lise’s desire to better herself was a selfish sin of vanity. Maybe she is the one being punished. To dare think this simple life wasn’t enough means enduring its struggle forever.

The feedback loop is undeniable as those who believe this are uneducated precisely because their lack of education refuses any other explanation. Science becomes the Devil because it (through doctors) becomes the last thing to touch the deceased. It’s therefore better to fear the ghosts of those souls not yet judged than to accept that God cannot be expected to make everything right. It’s better to twist yourself up into pretzels to make it mean something than to admit you might have been wrong. One arduous day suddenly risks a lifetime of hardship for everyone on that farm. Because while Lise may become an example to prove otherwise if she’s allowed to leave and thrive, any possibility for progress can be washed away with a single dying breath.

Lindeburg has brought to life what should be an antiquated issue that’s unfortunately proven all too prevalent in our current world. It may even be worse today since the people who tell themselves that their devotion to God will save them from a deadly disease (rather than allowing proven science to assist) are now vocal to the point of violence. Society has willfully allowed fear of the unknown to drive itself back centuries. That Lindeburg and cinematographer Marcel Zyskind make it look so beautiful only enhances the inherent danger within its madness. That Lise—a young woman excited to learn and evolve—can be drawn into the hysteria and feed the others’ delusions that she is at fault only reminds us how quickly we can fall.

As In Heaven played at the Toronto International Film Festival.