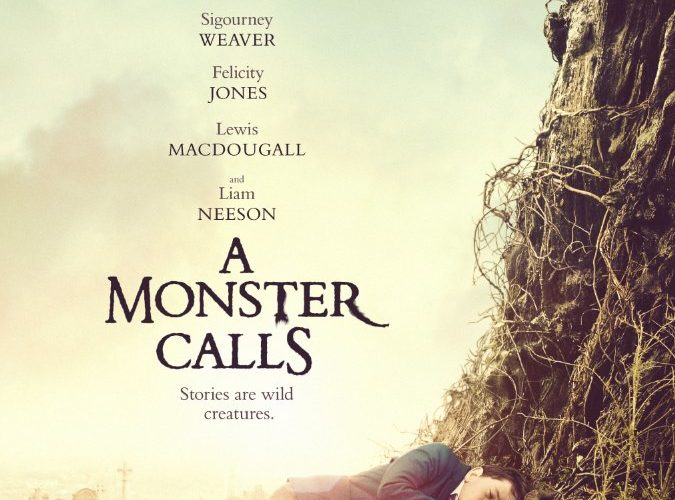

When your author and illustrator both win Carnegie and Greenaway Medals for the same book, you can bet Hollywood will come knocking. Even though the production is a joint effort between Britain (the majority of its cast) and Spain (The Orphanage director J.A. Bayona), it was Focus Features who scooped up the rights to Patrick Ness’ A Monster Calls. The decision was a no-brainer even without the accolades as it is a fairy tale proving a welcome return to storybook ilk of my own childhood. Dark enough to receive a PG-13 rating, it’s also profoundly moving in teaching someone that age (or a bit younger) a lesson in mortality. And just because the topic is difficult doesn’t mean you shouldn’t be unapologetically honest.

Who better to tell it than a terminally ill cancer patient in Siobhan Dowd, the writer contracted to bring the tale to life before sadly passing at forty-seven years young? Ness inherited the project from her and by going solely off of what his script and Bayona’s directing provide on-screen, I hope she’d be proud. There’s as much courage on display as there is grief, young Conor O’Malley (Lewis MacDougall) doing his best to cope with his mother’s (Felicity Jones) impending death. Or I guess it is her impending recovery, the boy proving steadfast in his belief that she’ll get better. It was she who told him so, after all. And she wouldn’t lie. So he cares for her after each treatment and awaits his miracle.

It’s been so long now, though, that doubt has crept in. Conor is ravaged by a nightmare, the ground opening to swallow his mother while his outstretched hand remains extended in horror at his inability to save her. He’s become conscious of the truth, desperate for her to admit it without deception meant for children much younger. But she refuses to quit, her language about alternative methods still glowing with hope. So he endures that nightmare, bottling the anxiety and torture until he’s visited by a waking one as well. This is the monster (Liam Neeson): a walking, talking yew tree with a fire in its eyes. He will tell Conor three stories and than the boy will explain the true meaning of his evening terror in return.

The most enjoyable aspect of A Monster Calls is that it’s both from Conor’s perspective and doesn’t try to be obtuse in metaphor because of it. There’s no a-ha moment for adults to find some hidden twist. This isn’t for them. Bayona blatantly throws a photo of Neeson on the boy’s grandmother’s (Sigourney Weaver) mantle and Ness follows every instance of frustration at his family with a monster-led tale thinly veiled as commentary on it. Conor believes his grandma to be an uncaring, cold witch so he’s told of a kingdom that existed in his backyard. The story’s just like those we’ve heard, but the villain and hero are harder to discern. Humanity is proven complex, evil often imagined and justice built atop horrific deeds.

This vignette is conjured through gorgeous watercolor animation, the aesthetic again toeing the line of being too mature for kids. But that’s a necessary choice as it is what earns their attention and focus. It’s like the old Jim Henson movies The Dark Crystal and Labyrinth. Their moral lessons are on their sleeves, the vehicle dark enough so the audience thinks it’s watching something it shouldn’t. Just as nightmares invade Conor’s consciousness, Bayona’s vision may attack theirs. It drills deep to hit their emotional core so they understand the pain of death and that it’s okay to be sad and angry. Children deal with tragedy as much as adults and need to be taught how resentment and rage are okay. They don’t negate the love and longing still burning beneath.

Soon the stories begin to invade Conor’s waking life, number two channeling his destructive nature for a heartbreaking release while number three removes fantasy completely so his pent-up aggression can escape in a violent whirlwind. Punishment is futile, his grandmother, father (Toby Kebbell), and principal each aware of this trying time and the difficulties it brings. It’s up to Conor to find his outlet through the monster. It’s he who holds the boy’s hand and leads him through the complexities of mankind to find his own honesty within. Death is coming and Conor can either retreat in fear or face it head-on with love. The journey from former to latter is inevitably filled with tumult. Each release is intensely freeing despite their destruction.

MacDougall must carry the film on his shoulders in only his second film credit, first as lead. He does a fantastic job doing so, his emotions ever-present either in quiet seething or deafening scream. He falls apart as necessary when faced with Jones’ deteriorating health and stands his ground whenever grandma or dad overstep their boundaries thanks to their own sadness. MacDougall holds his own with sarcastic retorts alternating against quivering lips and dangerous eyes. He’s tired and worn out to the point where he yells at his own monstrous manifestation for wasting his time. Life has aged him beyond storybook fantasy, but without it he may never grow past the tragedy that’s ripping him apart.

This film thankfully isn’t a dramatic piece gunning for awards glory, but rather a heartwarming adventure through the emotional landscape of a child unsure how to live. It is very sentimental, but that’s kind of the point. It’s for families to watch together with a powerful message able to guide our youth through the death of anyone from parent to sibling to grandparent to pet. The person dying is less important than the act itself. We’re watching grief’s stages and accepting a spiritual idea of immortality without the need for religion to give it a name. And by letting it exist in our world rather than a fictitious one, children can’t help but relate. There’s enough nuance to hold intrigue and enough compassion to be a resounding success.

A Monster Calls is currently playing at the Toronto International Film Festival and opens on December 23.