One of the best films to premiere at Sundance Film Festival was the Terrence Malick-produced biopic The Better Angels, directed by To the Wonder editor A.J. Edwards. Tracking three years of the to-be president’s upbringing, I said in my full review that “it’s a sublime, transfixing, and informative look at the early life of Abraham Lincoln.”

We were honored to get a chance to sit down for a one-on-one interview with the helmer during the festival to discuss his directorial debut. An eloquent speaker, who clearly has deep knowledge of the history on his subject, we touched on a number of aspects of the film, including parallels to Malick’s other work (specifically To the Wonder and The Tree of Life), spiritual aspects of the film, if Malick has seen it, the original title, premiering at Sundance, how he feels about comparisons to Malick, and much more. Check out the complete conversation below.

The Film Stage: I was wondering how editing on Terrence Malick’s films — and you worked as second unit director as well — inform the development process? Those were kind of side by side, and you were working on those films while you were developing this?

A.J. Edwards: Always, yeah, yeah. They’ve been in tandem and Mr. Malick was an integral of the origins of this picture. We had long discussions in the post process of The Tree of Life, while we were working together, and he was integral to sort of bounce ideas off of him, you know I would share with him the treatment and the screenplay, so he was essentially brainstorming the fundamentals of the production — the approach we had, the cast we had wanted to get, how we wanted to make the movie, and then also making sure that we got our meaning, which is the heart of the story being the two mothers and how Lincoln is a reflection of their goodness.

I know you didn’t edit this film, but I was wondering what your involvement was with it and did you bring anything from your previous experience working with Malick? With To the Wonder, I appreciated the cinema-as-memory approach and found a lot of parallels with that here.

Certainly, each picture that I have been able to edit has been a stepping stone in terms of knowledge and film understanding. And To the Wonder is no exception, in terms of its rhythms, it’s pace, the film feeling, like you said, memory or consciousness. So it’s not just a story. Films can be stories, memories, they can be fantasies or they can be regrets. They can tell the truth, they can lie and just like in our own heads, it’s not always linear. it can bounce around. Alexander Milan was the editor on The Better Angels and I’ve known him for a few years and he is rock solid in the cutting room and has great instincts and musical rhythm.

I know on Mr. Malick’s films the process can be really extensive, but did you have a shorter time putting this together. When did you shoot?

I know on Mr. Malick’s films the process can be really extensive, but did you have a shorter time putting this together. When did you shoot?

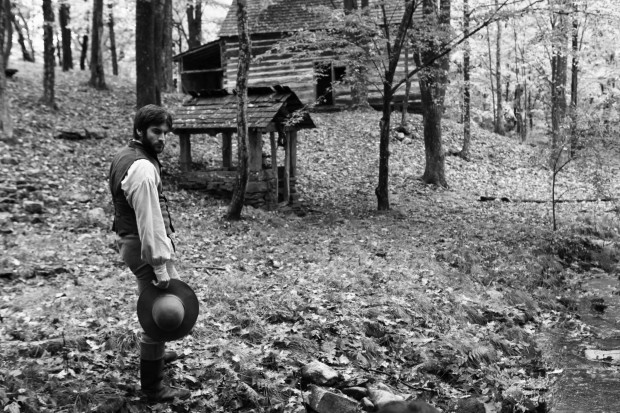

We shot this in October of 2012 and then we edited for about nine months, in Texas and New York, so it wasn’t too long, but a little longer than some. But I think it needed it because it sort of had to blossom and grow. We were out to discover and find things spontaneously, just like on set — it was the same during post.

Getting into some of the themes of the movie. I found it to be quite a spiritual movie. When Brit Marling’s character passes and you see her last gasp of air, then her walking through a doorway and then camera peering up to the heavens. Then with Diane Kruger’s character, I love the line when she says she will love Lincoln unconditionally, regardless of his feelings toward her, reminiscent of Christianity and God’s view of humanity. So, I was wondering if that was something you found historically or added and wanted to bring to the picture, or if you didn’t see it at all.

No, of course. I’m glad you noticed that. I think the death of Lincoln’s mother, Nancy (in the film, Brit Marling), I’m very proud of that sequence because of Brit’s emotional performance and even seeing her breath just naturally occurring on set like that and the music that we used there being a section from Hovhaness’ Mysterious Mountain, it all just came together very well I thought, and showing spirit… that death is not an end, it’s more like sleep and that the spirit moved on. That was the idea, that it left the cabin and went somewhere else.

And I think that line about unconditional love, that you were talking about, that Sarah Lincoln says is so important, with her wisdom and her love that she had to meet Lincoln where he was. He was a suffering child, he was in a lot of pain after the loss of what he loved the most, being his mother, and so she knows that his distance or lack of trust, as of then, that he had to learn to love her. It would be a process, it wasn’t something that happened immediately. She sort of tamed him and slowly made her way into his heart, sort of like The Miracle Worker or that Truffaut picture The Wild Child. He was someone that had to be sort of roped in and she so cleverly and tenderly did that to him.

And talking about the relationship with his father, I found it is sort of reminiscent of Hunter McCracken and Brad Pitt in The Tree of Life. I know you developed this film around then, was there a parallel there?

There’s certainly a parallel there, in their dynamic, but in the end, this film being based on the actual history of Lincoln, the relationship was there and the history of difficulties he faced with his father were long lasting. I think Dennis Hanks has a wonderful quote that said, “Each man failed to understand the other’s world,” and that’s a pretty telling quote that shows that they could not meet in the middle. They didn’t see things the same way, one being a man of the land, a farmer, a laborer, living in the wild. That was the life that he knew and the discipline he found important. Lincoln aspired to a life of thought, study, of rhetoric, learning, and I guess those notions and ideals were not as central to Thomas Lincoln’s understanding of what a man should be. It’s a somewhat tragic relationship they had, that was never quite settled as things are in life. It’s very mysterious. This story I think is still a bit divided between Thomas Lincoln’s character and what kind of father he was and how he effected his boy.

I found that really informative, like you were saying, with Mr. Crawford and those sequences, what he learned. You also show the first time he saw slaves, presumably.

Well, that scene in the movie I think is a bit more figurative, you know, because there is no account of that literally. Indiana was a free state at the time and had just come into the union and decided that it would be free and no slaves. Kentucky did have slaves. Lincoln would have seen them there and the only way he would have seen slaves in Indiana would be runaways. He did see slaves later when he went down to New Orleans as a teenager. He saw slaves auctioned and a family being separated, which was horrific. But that scene where he saw slaves was more suggestive of his future, than it would be being based on an actual event.

And with the casting how did that come about, specifically Braydon [Denney]?

He was found by our casting team led by Stefni Colle and Jake DeVito. They spent a year searching out schools, churches, athletic teams, all in Kentucky, so we wanted to find that real authentic voice, that accent that’s so specific, being Appalachian. It’s not just a southern accent, it’s a beautiful accent that they have and people often write about how Lincoln spoke, how he had such an unusual accent. When he would go up there he wouldn’t say Lincoln, he would say “Lincorn,” You could read about how someone documented how he would say things unusually. They thought he was a bit of backwoodsy fellow when he would speak casually. But then, of course, when he would rise to make a speech he was so compelling with his rhetoric…and all the backwoodsy nuances would disappear. But, yeah, Braden was such a wonderful find, he was a blessing to the film and he’s a very good boy.

I’m curious in the writing process, is there certain events you knew you had to hit, especially in terms of his family relationships, but was a grab bag of things where when you were on set you could discover them?

Certainly, there were definite story check points we had to hit in and I’m pretty proud of the historical authenticity of what we achieved there. But also, in terms of discovery, those story points were sort of the foundation on which other things could be replaced, being the behavior and expression that we captured on set, which happened either through improvisation or spontaneity. Maybe even before we set out to shoot a scene or the scene ended, we shot the pages, and then suddenly something new happened with the children or the children and the mother’ and we were like “oh, hurry up capture that, you know let’s get going.” It’s almost like capturing wild animals, you have to be quiet and creep up on them and so I’m especially happy with that, in terms of when they’re balancing on the fallen tree, suggestive of trust and a relationship developing. That suggested that more than any dialogue or set-up scene could have. It was so casual and light-hearted and kind of paper thin.

In terms of the voiceover, you said that’s from an actual document, so as soon as you saw that document did you have that thought you were going to use it?

All of the voiceover in the picture is based on an interview with Dennis Hanks’ cousin, made in I think around 1890, something like that, and published around 1900 by Eleanor Atkinson, a great journalist, and it’s that document that’s so integral to understanding Lincoln’s Indiana years, because other than that, there’s not much recorded of words from the mouth of people that were walking with him and living with him, so all the voice over in the picture is verbatim his own words. But I would encourage people to seek it out, cause we just used 1/100th. I wish the whole movie could have been the interview, cause it is so funny, but also so emotional and sad at times. It has the bitter sweet quality of what those times in that life…you know, what that life must have felt like.

A lot of the film is capturing their emotion on their faces. Because there’s only a few times when Braden speaks during the film, was there any push and pull in terms of in the edit room where you had more dialogue you wanted to use, but you cut it out to serve the film?

Certainly, and the dialogue wasn’t minimized in post. It was sort of that way from the beginning. There was a little bit of minimizing, but not much. It wasn’t to dodge anything, because the performances were excellent. Jason [Clarke], Wes [Bentley], Brit [Marling], and Diane [Kruger] all just were so wonderful, but I think in Braydon’s case, his being a quiet figure in the film was more to preserve his mystery and keep him as an icon that represents so much to all of us, American or not. In historical research, they actually did talk about how quiet he was as a child. They said he was solemn as a papoose, is the description that Dennis said. And he was quiet as a child, there was a neighbor that said, ‘I would have thought that his step-brother Johnny would have been president before he would be,’ cause they said that young Lincoln really didn’t talk much. He was a loved boy, he had friends, he was a great wrestler, he had a good sense of humor, so he wasn’t a loner or a strange boy, but he was quiet and reserved.

I feel like it’s in the last few years I’ve seen so many movies that have thrown out Malick comparisons, which I don’t see many of them. I don’t know if you saw Ain’t Them Bodies Saints last year, which I loved that film, but I didn’t necessarily see a lot of the comparisons that were made with that. The camera movement was a lot more reserved and restrained, compared to Lubzeki’s camera style in Malick’s films. But there’s a lot elements in this film — Matt Lloyd as cinematographer and I know Hanan Townshend did the score – that feels like Malick’s touch was on. I was wondering how you feel taking on that style, because I believe it does earn those comparisons. Did you have any trepidation?

For sure, yeah. I think the camera style was certainly influenced by him, but I think it’s not just a stylistic choice, but also a functional one. The roving camera is important editorially for ellipsis and jump cuts. You can’t jump cut a static shot. You can, but it looks like Husbands and Wives or something. It’s just that you can notice it more, so without coverage, if you don’t have wide shot, middle shot, close-up, coming around over the shoulder all of that — which we didn’t do, we shot it more like a documentary — If you don’t have coverage, you’re forced to jump cut, and so it is stylistic, but it’s also functional, the roving camera. It feels more like you’re there, it feels like consciousness, that you are roaming with them, walking around with them, looking around with them. Just like right now I’m talking to you, I look up at the window, I see Jake over there, I look at the pool. So the camera moves so, that’s how I guess we are. The style though can also be seen in films like Pather Panchali or an Ozu’s pictures or Ugetsu by Mizoguchi or Bresson. You know the way sometimes Bresson would focus more on what was moving in the frame, rather than who’s talking. He would focus on the action, so wherever the action was, he would be recording that as opposed to the image being a vessel for dialogue, like theatre. You know that’s what theatre is, but cinema is different.

Has Mr. Malick seen the film?

He’s seen the film, yes, and he was encouraging all along. He wasn’t able to be there during preproduction, on set, or even in the the cutting room because he has two movies of his own that are going to be coming out soon and are excellent, but he was only a phone call away and was so encouraging and so inspiring. Like in boxing, he’s a corner man, he’s that man that’s got your back and supports you and he wants people to stand on his shoulders and they’re big shoulders to stand on.

So in terms of the schedule, you are working on his two upcoming films as well, correct?

That’s right.

So were you just like, “I’m going to take a break.”

It was finishing To the Wonder with him and then went and spent about a year and a half doing this and then having returned to him now for post on these two pictures along with a great team. It’s a sizable editing [team]. I love them all, it’s great to all be together. It’s like a family cutting.

In terms of coming to Sundance with this film, you’re also headed out on a bigger festival tour. I think it’s going to Berlin, as well?

Going to Berlin, yes.

Was it kind of always in the plan to have it finished by this time frame and have it premiere in early 2014?

We didn’t have a specific date in mind as to finish or to what festivals we wanted to attend, but being here and after being accepted, there is no greater platform in North America than Sundance and I can see how lucky it is for the film to be here. It’s been a gift, it just seems like the reception has been warm. It’s only been a couple of days, but the kind things people have said to me, it’s been very nice and so Sundance has been wonderful. I’ve never been to Berlin and so I’m excited to go and they seem like a people of cinema. They’re so serious, they’re so intense and I love that and what greats they have, like Schlöndorff, Wenders and Herzog. So those are all the old-timers, the masters, so it’s an honor.

I know this is in the New Frontier section here, which are film off the beaten path. I was wondering if that was a decision that Sundance brought to you and said we would like to have it in this section? I can easily see this excelling in the competition line-up, as well.

No, I hear you. Sundance decided the category in which the film would be played and I was very happy to hear that someone thought… I read the description of what New Frontier meant and I thought, well gosh, I thought this was a very classic, traditional movie and sort of timeless in that way. So I was so happy that Trevor Groth and Shari Frilot and all the other programmers thought that there was something sort of boundary-pushing or new and fresh and bold in it, cause I think that’s what the ultimate goal of the team was to do something, to make new forms, something fresh. You know, the slogan of the film festival said, “Sundance Film Festival: because we’re all seeking something more than the same old story,” and I thought, how flattering is that, to have something new.

That’s great and I also wanted to ask you about the title. Originally, when we wrote about it, it was Green Blade Rises. I think The Better Angels fits as far as the spiritual angle I was talking about. Where did you find that title and how long into the process did you change it?

The Better Angels is the conclusion of Lincoln’s first inaugural address, when, at the start of The Civil War, Lincoln spoke after being elected president and the country had just divided itself after the confederacy was being formed. People, now that Lincoln was in, said that we’re out and so it was very turbulent time and that’s when he said we’ve got to listen to the better angels of our nature. He was appealing to that and saying for us to remember the virtues on which this country was built: fraternity, faith, justice, quality, and independence. I love the title and it was Terry’s… Mr. Malick’s suggestion — do not call him Terry [laughs] — to call the picture that, I’m so thankful. Green Blade Rises, was a hymn that I love, in a sort of sentimental way. But also that’s a passage in Isaiah talking about the tender shoot out of which the Messiah will come. Not that Lincoln is the messiah, but you know the idea, that from nothing can come something so great. From this soil, the green shoot of life and something so wonderful could sprout, so that was the idea of that whole title.

I also had a question just about the bookends to the movie, was that something you had planned all along? I feel like that’s a great encapsulation of his life in terms of showing what he would become and what happened.

I’m so glad you noticed that, cause it was the associate editor, Jamie Meyer, that pointed that out and really thought that was a strong structural idea and he would say that — I never thought of it that way — but with the bookends, there are these two totem poles and in between is this rushing narrative, but on either side you have the prism for which to view the film. The D.C. Memorial was to give the idea of, just like in ancient Greece, you’re entering through a temple for which a God has venerated. He’s such a hero, he’s the Odysseus of this country. So just to take away the notion, we’re so familiar of him in commercials and all sorts of iconography, we carry him around in our pockets, on $5 bills and pennies, so it was just to be a big reminder with silence and veneration of the great stature that he has. And then at the end of the picture with the Sarah Lincoln cabin, that was the real cabin in Illinois. Tom Lincoln’s cabin there in Lerna, Illinois. It was so wonderful to end the picture on complete historical authenticity, which is the actual space where she had received the news where her son was assassinated. It allowed the voiceover just to play over the tranquil, actual space and just end on a note of calm, peace, and bitter sweetness.

Wrapping up, after going through the experience of directing, is that something you can see yourself doing again, or do you prefer the editing suite?

I’d like to do both. I love editing and so, I will continue doing that, and directing this was fantastic. So, yeah, I plan on continuing as long as the resources were available.

The Better Angels premiered at Sundance Film Festival 2014. One can see our full coverage of the festival below.